The News

Skyrocketing power demand from data centers will help push the US offshore wind industry out of the doldrums, Ørsted Americas CEO David Hardy told Semafor.

One of the world’s biggest wind farm developers, Ørsted has had a rough time over the last two years: Rising construction costs, permitting delays, and other challenges forced the company to walk away from two major projects in New Jersey and book more than $4.5 billion in impairments since 2023, sending its share price to one-third of its 2021 peak. The headwinds aren’t over yet, Hardy said at Semafor’s Nights of Net Zero event at Climate Week NYC, as the supply chain for offshore wind hardware looks likely to lag behind demand for the next several years, and uncertainty about the survival of Inflation Reduction Act tax credits in the event of a Donald Trump presidency leaves project investors skittish.

But the US push to compete with China on AI development is helping secure the clean power industry’s long-term future, he said: “With the overall growth of energy demand, we really do need all of the above. I just don’t think this country can afford to slow [renewable energy deployment] down. In six months I could easily see five to seven new offshore wind projects with new offtake agreements and people putting their foot back on the gas.”

In this article:

Tim’s view

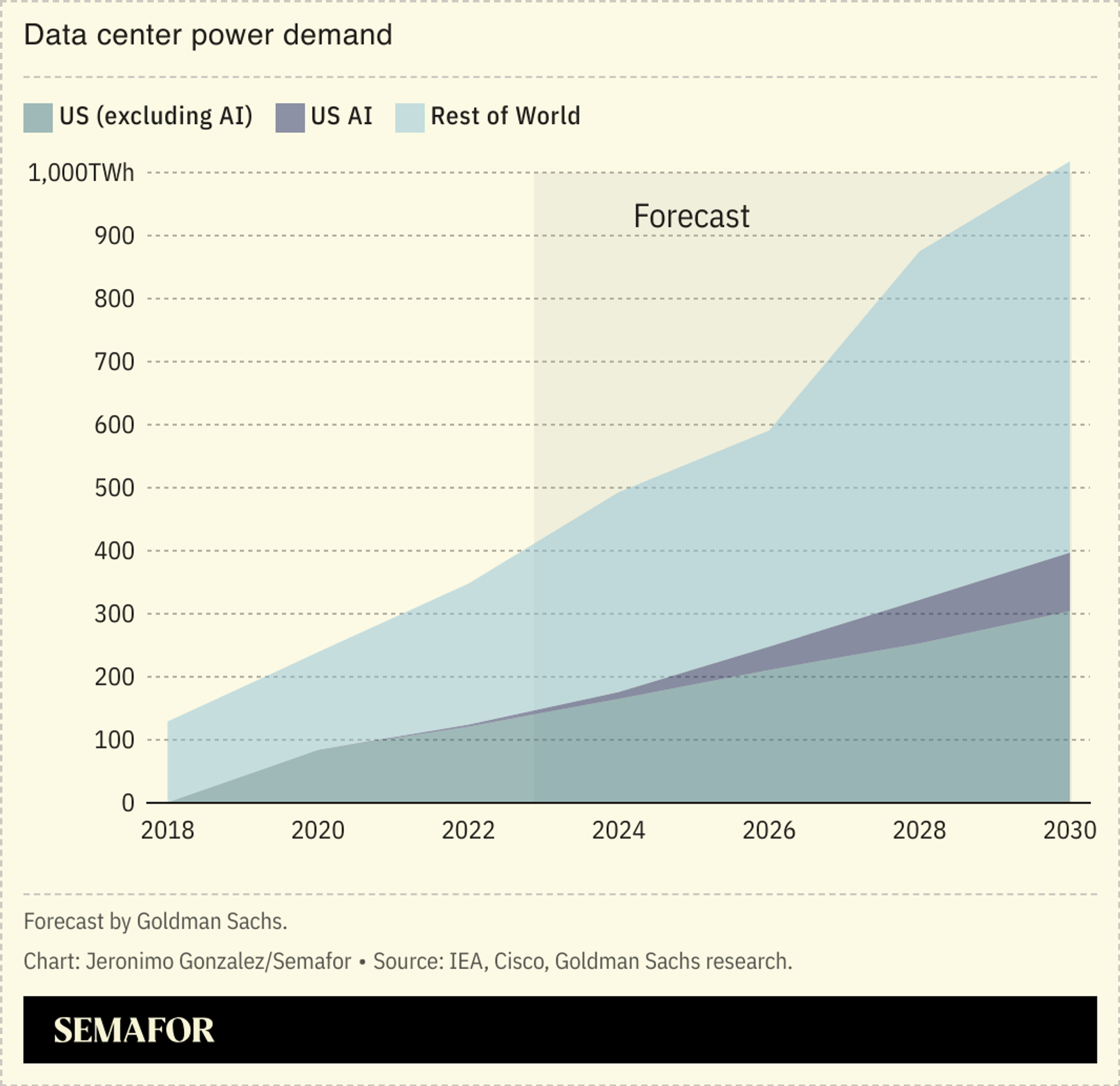

The AI-fueled boom in power demand is a hot topic at Climate Week, and the mood of the conversation is shifting. Earlier this year, when the scale of energy that will be needed for data centers started to become clear — forecast to reach up to 9% of US power consumption by 2030, double the current rate — the climate community was gripped by a sense of panic that the AI scramble would turn into an emissions nightmare. That anxiety is changing to excitement as more energy executives like Hardy say that Big Tech could be a powerful and sorely needed ally in the financing of clean power.

“We got this,” Arshad Mansoor, CEO of the Electric Power Research Institute, a research organization supported by the utility industry, told me. “Having the tech and energy industries come together will actually accelerate the clean energy transition in the long run, because they’re sharing the financial risk and sharing a need they both have, and the tech companies’ need is very urgent.”

Tech leaders who used to take power for granted increasingly see it as perhaps the biggest bottleneck in the data center buildout. But for an industry as deep-pocketed as theirs, the upside in staying ahead on AI far outweighs the cost of building energy infrastructure. Tech companies have the willingness and wherewithal to make projects happen that never would have been possible otherwise. The clearest example is the groundbreaking deal announced on Friday between Microsoft and Constellation Energy, under which Constellation will restart the mothballed Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania and sell all of its 835 megawatts of power to Microsoft for 20 years. When the plant was shuttered five years ago, Constellation never thought it would come back, Chief Strategy Officer Kathleen Barrón said at the Nights of Net Zero event. The AI boom changed the calculus, and when Constellation started negotiating the deal with Microsoft, it found a client willing to pay a premium for steady clean power. The deal was so good that Constellation was willing to pay the $1.6 billion needed to restart the plant out of its own pocket, Barrón said, even though it will take several years before any revenue from Microsoft comes in. Constellation’s share price is up 22% since the deal.

Restarting Three Mile Island won’t benefit the region’s households and other power consumers, per se. But it’s a model for how data center demand can be served without draining the existing grid, and without building new fossil fuel assets. Opportunities to restart mothballed nuclear plants may be exhausted. But there are other ways to achieve a similar outcome without building new plants from scratch, a process that would be slow, and expensive even by tech standards. Existing nuclear plants can be cost-effectively upgraded with new hardware to squeeze out more electrons, Barrón said. Transmission and distribution lines, likewise, can be upgraded with hardware and software to expand their capacity, making it easier to incorporate more renewables and batteries. And utilities are beginning to negotiate with data centers on demand response, Mansoor said: If, during the few dozen hours annually when power demand is at its highest, a data center can shut down or run on a higher-cost local power source like a hydrogen or biofuel-fed generator, it can save the utility from needing to invest in gas-fired plants.

The most important aspect of the Three Mile Island deal is that it adds to the grid rather than drawing from it, Microsoft President Brad Smith said in an interview at Semafor’s separate Next 3 Billion event on Tuesday. Additionality needs to be a core principle for tech companies in their data center push, he added. Indeed, in a recent column, Brian Deese, a former White House economist and adviser to the Kamala Harris campaign, argued in favor of mandating additionality for data center power deals.

Room for Disagreement

The Three Mile Island deal isn’t easily replicable, and any push to serve data centers with nuclear power will be constrained by the supply of uranium fuel, permitting, and other issues. Between that and the fact that renewables alone won’t be able to provide sufficient baseload power for AI, it’s likely that new gas turbines will be built in some cases. The data center boom can’t entirely dodge some increase in emissions.