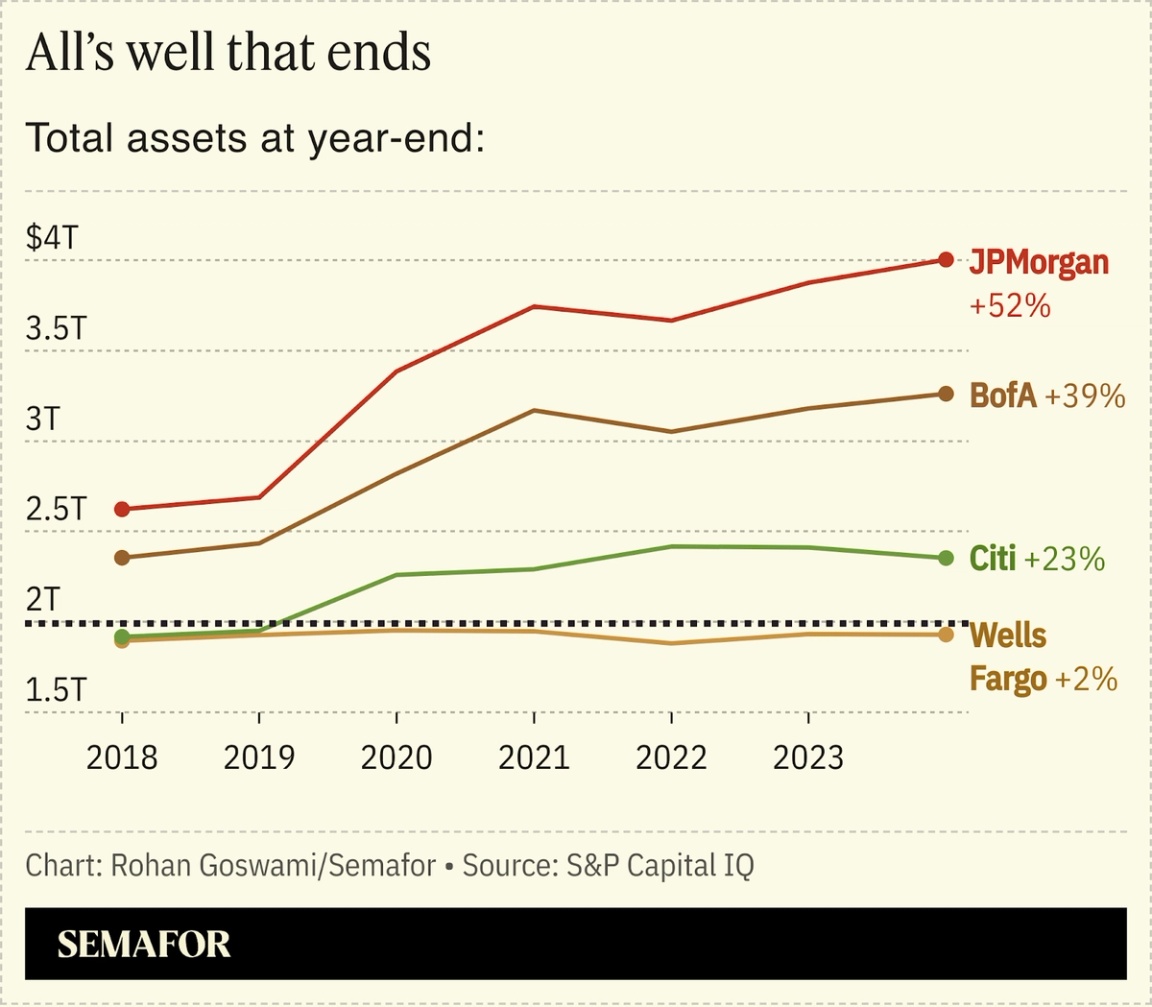

Charlie Scharf cemented his reputation as a turnaround master this week, after the Federal Reserve lifted a painful asset cap that had limited its size. The question now is whether Wells Fargo can make up for lost time.  The lid, imposed after Wells was caught opening thousands of fake accounts in an effort to pad its numbers, kept the bank under $2 trillion of total assets since 2018 and complicated cleanup efforts by Scharf, a former JPMorgan and BNY executive hired in 2019. As rivals scooped up competitors, added branches, and won the loyalty of a new generation of savers and spenders, Wells was stuck. And staying under that asset cap became hard during Covid, when banks received a flood of deposits that Wells, hampered by its size limit, couldn’t easily channel into new business. “We weren’t focused on expanding the product set [or] improving the digital capabilities because we were so focused on creating the right infrastructure to satisfy the regulators,” Scharf said at a Bernstein conference last week. Getting out from the Fed’s restrictions is key to Wells Fargo’s ambitions — not for the first time — to compete in Wall Street dealmaking. Helping companies write big checks for takeovers requires balance-sheet space, which the bank will have again for the first time in seven years.“Our corporate investment bank has been limited in terms of what they can do,” Scharf noted. He has hired star bankers including Doug Braunstein, Fernando Rivas, and tech dealmaker Jeff Hogan to compete with firms like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan. Cracking into the top tier of investment banking has historically been a fool’s errand — ask Bank of America and Citigroup executives — but Wells Fargo has picked up some early wins. It advised on the $19 billion merger of Chart Industries and Flowserve this week and advised Worldpay on its $24 billion sale to Global Payments. |