The Scoop

U.S. rules governing how activist hedge funds and hostile bidders can accumulate stock positions in secret haven’t been meaningfully changed since 1968.

Now, the Securities and Exchange Commission is finalizing reforms and likely to back off its most far-reaching proposals, people familiar with the matter said. That retreat would hand a win to investors like Bill Ackman and Carl Icahn, and their brokers on Wall Street.

At issue are rules on when and how investors have to disclose stakes of at least 5%, which have been used to push for changes at some of America’s corporate giants. The agency’s proposal to narrow the deadline for investors to publicly report their stake, from 10 days to five, is likely to survive in the final measures, people familiar with the matter said.

But two other major rule revisions the SEC proposed in March are likely to be abandoned or significantly pared back after feedback from market players.

One would sweep stock contracts with Wall Street banks – which mimic exposure to stock ownership but don’t carry the right to buy the underlying shares – into an investors’ stake for purposes of calculating the 5% trigger. That proposal would also rope those banks into a hedge fund’s camp for purposes of determining whether an investor “group” had been formed.

This fall, the two camps made their case directly to the SEC, people familiar with the matter said. Wachtell, Lipton, the staunchly pro-management law firm, sent two heavyweight lawyers, David Katz and Leo Strine, to lobby the SEC for tighter rules. Stephen Fraidin of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP and Berkeley Law’s Frank Partnoy went to argue the case of activists.

No decisions have been made, and the SEC could choose to re-propose preliminary rules for a new round of comments from the public. A final rule is expected sometime this summer, the people said.

In this article:

Liz’s view

The investing world moves faster than it did in 1968, and the speed with which market information moves means the SEC can tighten the 10-day window and still keep the balance between investors, who need an incentive to make bold bets, and the rights of corporate managers they target not to be blindsided.

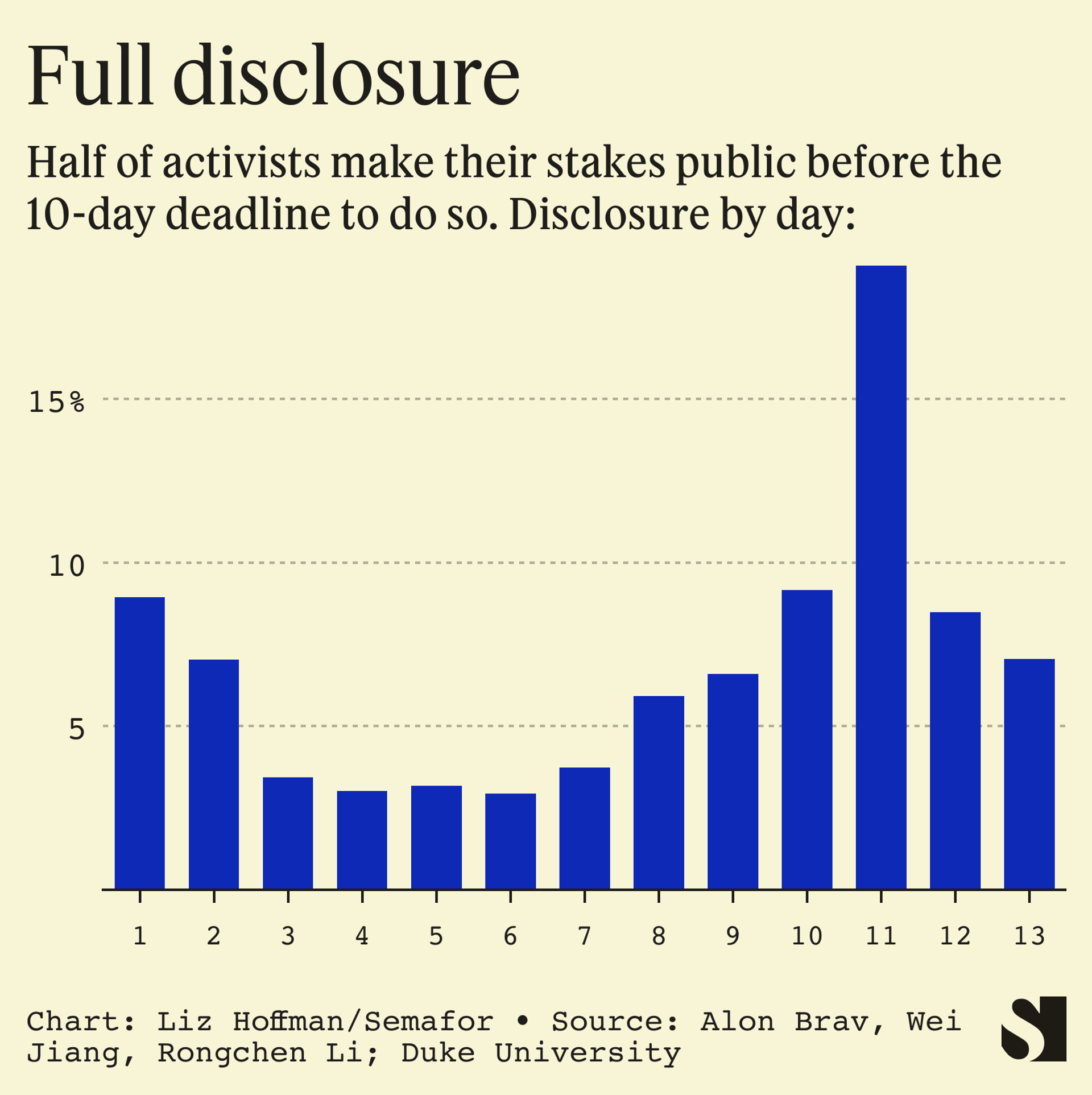

Most activists don’t even use the full 10 days to build their stakes. Even one of the biggest activist hedge funds, Elliott, isn’t opposing that move.

But the SEC’s other proposals would hamstring activists’ ability to use common trading strategies, like swaps, that boost their economics but not their strongarm power. And they would make it impossible for most banks to work with activists, who can play constructive roles in shaking up entrenched management or calling out poor performance.

Take the swaps rule. Hedge funds use swaps contracts, which are cheaper than outright share purchases, to boost their economic ownership in companies but don’t give an activist any additional votes. The contracts require investment banks to deliver the cash value of the stock in the future, so they go out and buy the underlying shares. The SEC’s proposal would include those swaps in the investor’s position for purposes of triggering the 5% threshold.

The proposed rule would also require that a bank disclose every transaction it made in the shares in issue – an insane requirement for a large Wall Street brokerage desk, which might trade thousands of individual stocks in any given day.

And if the SEC really wants to breathe some life back into the 13D rules, it could start by sanctioning Elon Musk for flagrantly violating them in his pursuit last spring of Twitter. He blew the filing deadline; trading records show he owned 5% of the company by March 14, but he didn’t make his first filing until three weeks later.

And even then, he disclosed his stake on a form reserved for passive investors who don’t plan to seek control of the company or influence its board. By that point, Musk had unleashed a string of tweets criticizing the company’s management and had talked to Twitter about joining its board for weeks.

Room for Disagreement

Supporters of the rule argue the swaps market does need more transparency, and cite the swift collapse in 2021 of Archegos Capital Management. The fund had built up huge positions in Viacom, Shopify and other stocks through shadowy swaps trades, in some cases equivalent to 50% or more of the float – all without having to make so much as a single disclosure.

When the stocks fell, it started a swift collapse that ultimately cost the banks Archegos was doing business with $10 billion. “This combination of leverage and anonymity proved devastating,” Wall Street nonprofit watchdog Better Markets wrote to the SEC in support of the changes.

Six Democratic senators, including Elizabeth Warren and Sherrod Brown, have made the same point. They argue the changes are needed “to ensure that [swaps] are not used to hide a stake in [a] public company or a large position that could destabilize financial markets.”

Notable

- WSJ on how Archegos’ blow-up renewed calls for more transparency in swaps. “The private marketplace was not aware of the extent of the risk exposure, because it did not have enough information,” one expert told the paper. “The antidote for that is more disclosure.”

- A paper commissioned by a group of investors dove back into the congressional record to untangle the origins of the Williams Act, and argues that no reforms are needed.