The News

It was only three years ago that Exxon’s shareholders, dismayed by its seeming indifference to climate change, voted out a quarter of its board. The victory of a tiny hedge fund against the world’s most powerful symbol of the fossil-fuel era captured the rise of progressivism in corporate America and seemed to portend more to come.

Fast forward to Sunday, when Exxon sued two of its investors that are pushing a climate agenda at the energy giant.

The shareholders, which both acknowledge they only bought Exxon stock to get ballot access, want the company to speed up its carbon-emission reductions and to present “new plans, targets, and timetables” to investors.

In a first-of-its-kind lawsuit, Exxon says the proposal tries to micromanage the day-to-day running of the company and that a nearly identical ballot measure failed to crack 10% support last year.

In this article:

Liz’s view

That Exxon — Exxon — feels comfortable throwing its corporate might against a couple of low-budget activists says a lot about how quickly the political weather has changed.

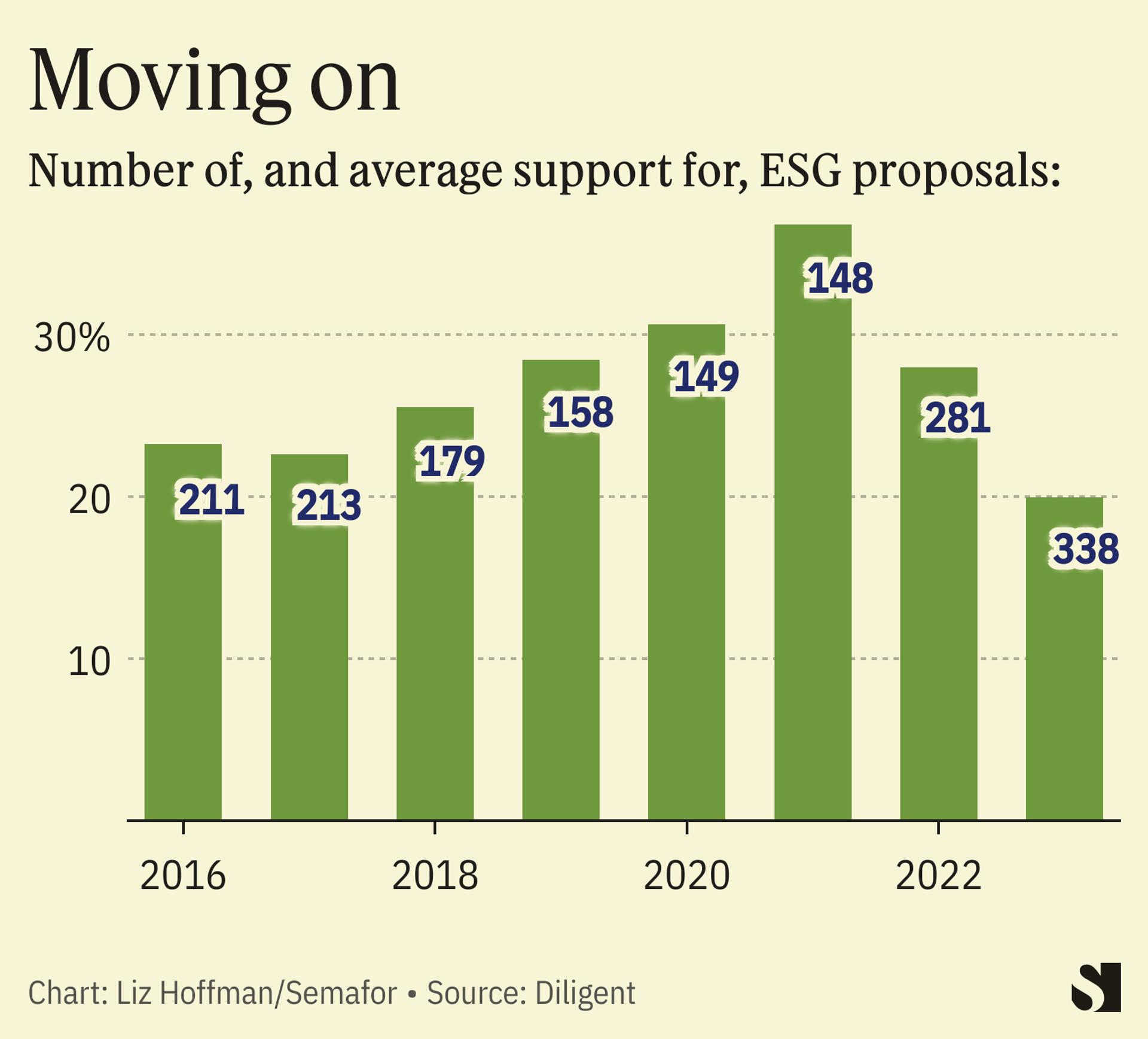

In the late 2010s and early 2020s, many companies embraced progressive demands under pressure from their investors, customers, and employees. They set targets for workforce diversity, and tied CEO bonuses to hitting them. The share of Fortune 500 companies with explicit carbon-emissions targets doubled between 2020 and 2022. They mostly tolerated shareholder proposals that rarely passed, but showed a growing level of investor support for ESG causes.

That era is over, and there is growing support for the idea that the pendulum has overswung the mark. Quotas are being reframed as targets. (“They were illegal then, and they’re illegal now,” the chief people officer of a larger public company told me last week. “The only thing that’s changed is that they’re not popular anymore.”) Companies are backpedaling on commitments to contract with minority-owned vendors. Chief diversity officers hired in the wake of #MeToo and Black Lives Matter are quitting in droves, and CEOs are using layoffs as an excuse to gut their departments. Starbucks sued its union over, somehow, Gaza.

Even Davos, which has arguably done more than any organization to curate and amplify what might now be labeled corporate wokeism, lurched notably rightward this year under pressure from, of all people, former PayPal CEO Dan Schulman, a liberal business icon who once nixed an office planned for North Carolina in protest of an anti-LGBTQ bill. That Semafor scoop from last week is worth reading for the delightful stew of interests — Gulf oil money, Republican beltway strategists, and a retired CEO mulling his legacy — conspiring to tamp down corporate wokeism.

From the mid-2010s to 2022, business was good. Bottom lines were fat, the world was relatively calm, and CEOs had the luxury to spend their time on big ideas. Now they’ve been kicked down Maslow’s pyramid from leisurely self-actualization to bare subsistence, and no longer have the time, credibility, or money to make ESG a priority.

Much of this was brewing quietly before the Oct. 7 attacks in Israel, which pushed them into the open and gave political cover for business decisions.“We had a movement — I think it’s fading away — largely understood as ‘wokeism,’ where people said in public lots of things nobody believed they believed in private,” Alex Karp, the CEO of Palantir, said last week.

Exxon could have let this proposal onto the ballot and watched it fail, just like it did in 2022 and 2023. But the case, filed in business-friendly Texas, feels designed to send a message and perhaps force the Securities and Exchange Commission, which has largely abdicated its role in policing corporate ballots, to weigh in.

Engine No. 1’s victory against Exxon in 2021 may end up being the high-water mark of corporate ESG, not the beginning of a surge. And its current lawsuit may punctuate the era.

The View From Larry Fink

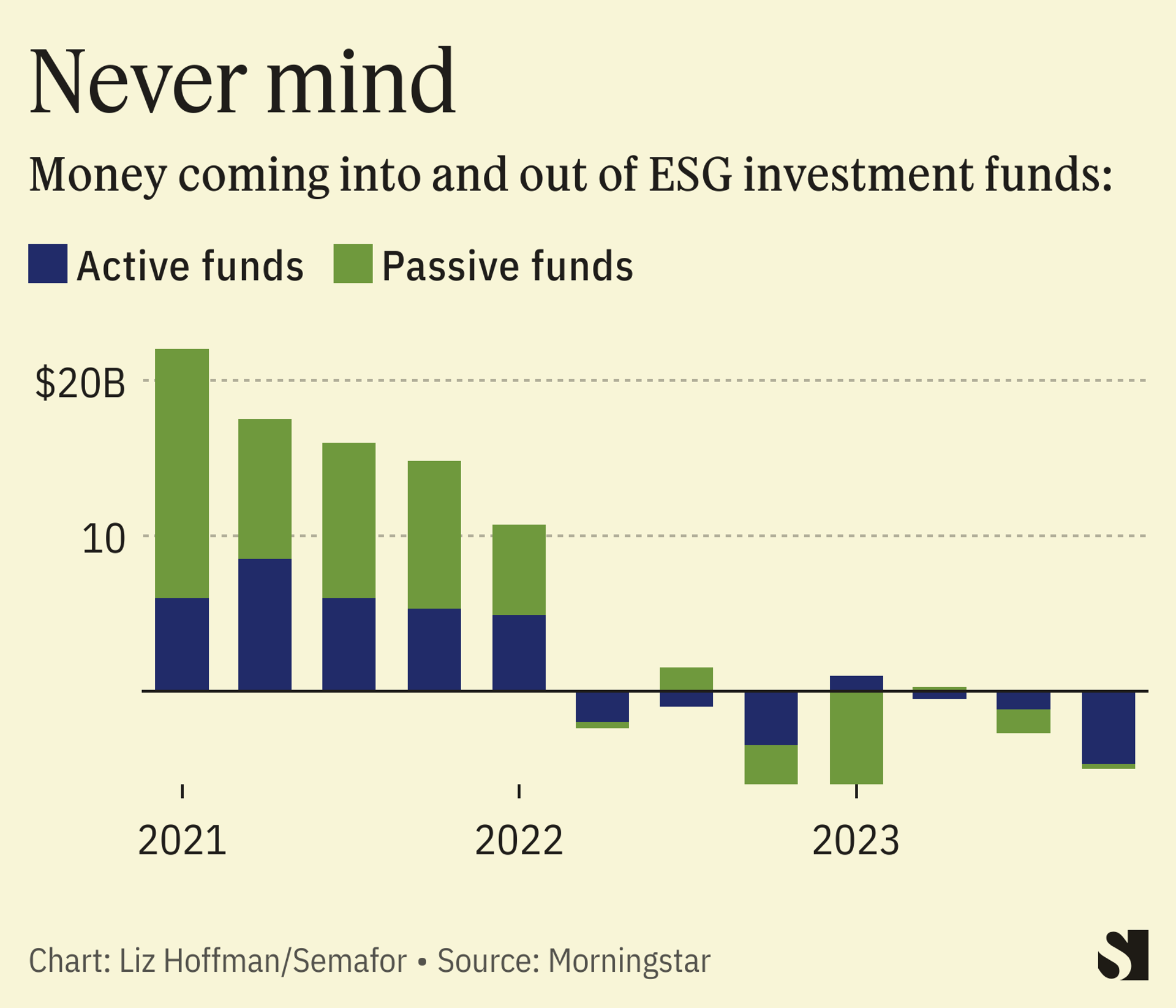

Big investors, like CEOs, have lost patience with ESG. Even BlackRock, which did more than any other major investor to create the movement and push it onto corporate agendas, complained last spring about “an uptick in the number of … single-issue proposals where the request made did not have economic merit.” Its 2024 investment priorities dropped references to global warming included in past years.

More broadly, investors’ enthusiasm for ESG peaked in 2021, when the average ballot measure got 37% of the vote, according to Diligent. That year, activists put 21 climate-change measures on corporate ballots and won majority support for seven of them, according to data from ESGAUGE. Last year, they went 1 for 63. Average support for workplace-diversity ballot measures fell from 54% in 2020 to 20% last year.

Notable

- Dropped from BlackRock’s investing playbook this year: “we expect companies to articulate how they are aligned to a scenario in which global warming is limited to well below 2C.” —Financial Times

- The problem with ESG, writes Bloomberg’s Merryn Somerset Webb, is that its definition is constantly changing. Russia’s war cleanses defense stocks, and the social unrest that energy insecurity brings changes the calculus on fossil fuel companies.

- Exxon would be better off letting this proposal die at the ballot box, not in court, writes Breakingviews’ Rob Cyran.