The News

South Korea’s demographic crisis worsened as new data released Wednesday showed a record low number of childbirths last year.

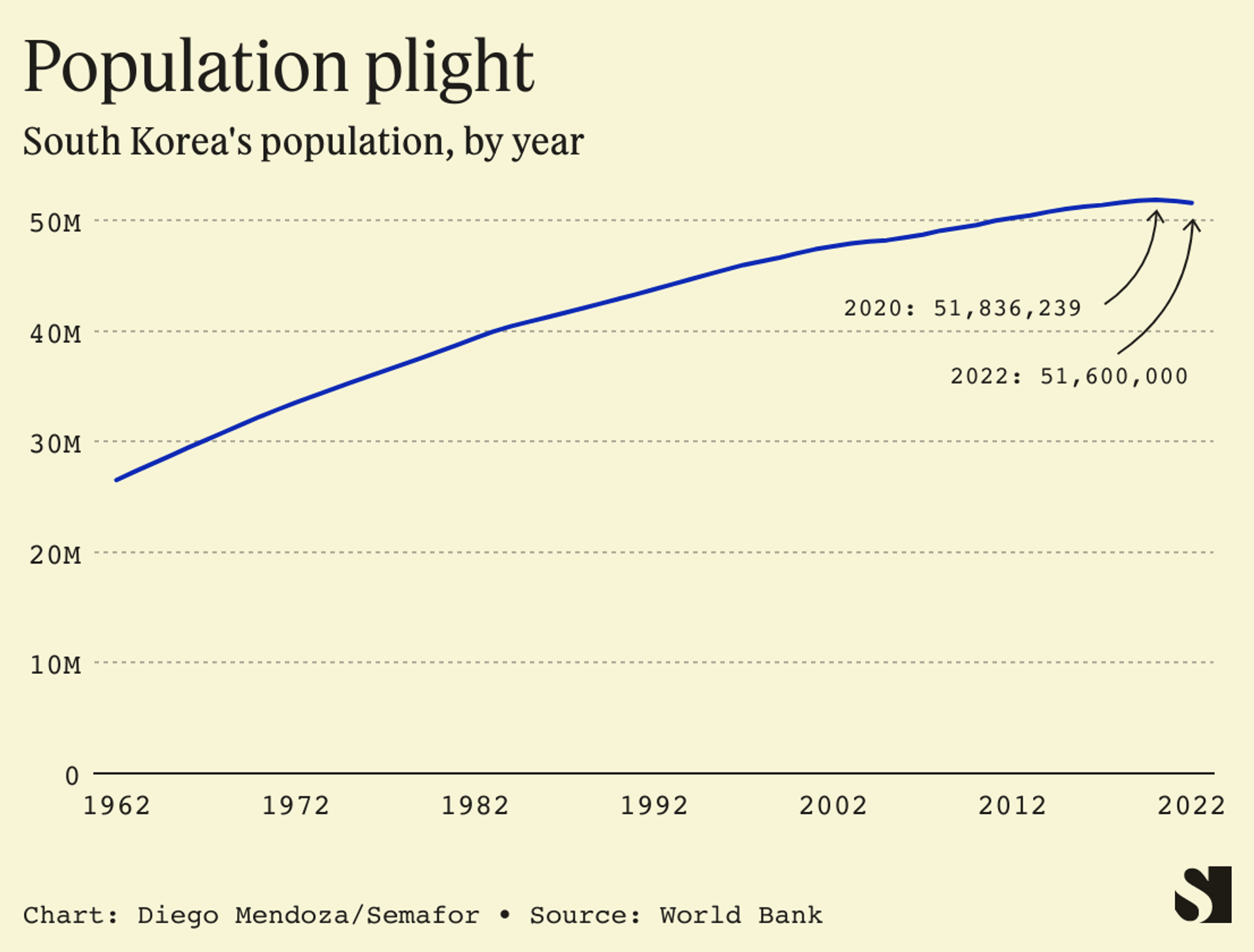

Only 249,000 babies were born in 2022, a 4.4 percent drop from the previous year, reported Yonhap News Agency. The fertility rate fell to 0.78, the lowest since 1970. Experts say the rate should be at least 2.1 to keep South Korea’s population stable at 52 million.

After decades of rapid growth South Korea’s population shrank for the first time in 2021, with further drops expected. But it’s not alone in grappling with the consequences of population decline. Here’s how governments across the world are trying to mitigate:

The View From Japan

For years, Japan has warned of a demographic disaster as young couples refuse to have children. There were less than 800,000 births last year, new government data shows, the lowest since the country began recording births in 1899.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida had previously said the country was “on the brink of not being able to maintain social functions.”

Kishida told lawmakers that they should place “child-rearing support as our most important policy,” adding that the government would set up a new agency in April and double its spending on child-related programs.

Tokyo has implemented several policies for more than a decade in response to the crisis: from government-sponsored speed dating nights to urging the workforce to log off early and use their remaining energy to procreate.

More recently, the government has pushed forward a “child-first social economy” in an attempt to encourage couples who want children with financial incentives and protections.

However, it seems few are being wooed. One woman interviewed by The Guardian on the population crisis said that she has no interest in having children because society still sees women as primary caretakers, often forcing them to drop their careers.

The View From Germany

Germany’s population took a hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some communities are now warning that they are in desperate need of a younger labor force to support local economies.

In response, the government in 2020 relaxed some of its immigration laws in an effort to bring in more skilled workers from outside the European Union. While this has contributed to some growth, experts say that migration cannot solely fix future hurdles for the economy.

The View From China

China’s population fell for the first time in six decades last year, prompting immediate governmental responses in an attempt to fix a potential crisis that many blamed on the country’s decades-long one-child policy and systemic pressures on women as primary caretakers.

In addition to offering paid maternity leave and maternity insurance, some provinces like Sichuan are now allowing people to legally register their children regardless of the parents’ martial status, a move seen by some as a way to encourage unmarried couples and single women to have more children.

The View From Russia

Russia’s population has not bounced back from its peak after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It saw a mild recovery in the last decade, but began to dip again after the COVID-19 outbreak.

In 2021, President Vladimir Putin approved the final phase of a years-long population regrowth program that is expected to run until at least 2025.

Part of the program incentivizes couples having kids, such as providing free land to families with three or more children. Another component addresses the health problems of its populace, with Moscow hoping to reduce binge drinking and smoking rates over the next few years.

Notable

- South Korean society needs to embrace feminism and reject President Yoon Suk Yeol’s misogynistic policies to boost birth rates, author and journalist Hawon Jung argued in an op-ed for The New York Times. Given the crushing societal expectations of women coupled with pervasive sexism, Jung writes that it is no surprise that a large percentage of South Korean women have no plans of motherhood or even dating.