The News

South Korea’s birthrate rose for the first time in nearly a decade, preliminary data showed Wednesday, raising hopes that the country has started to turn a corner on its demographic crisis.

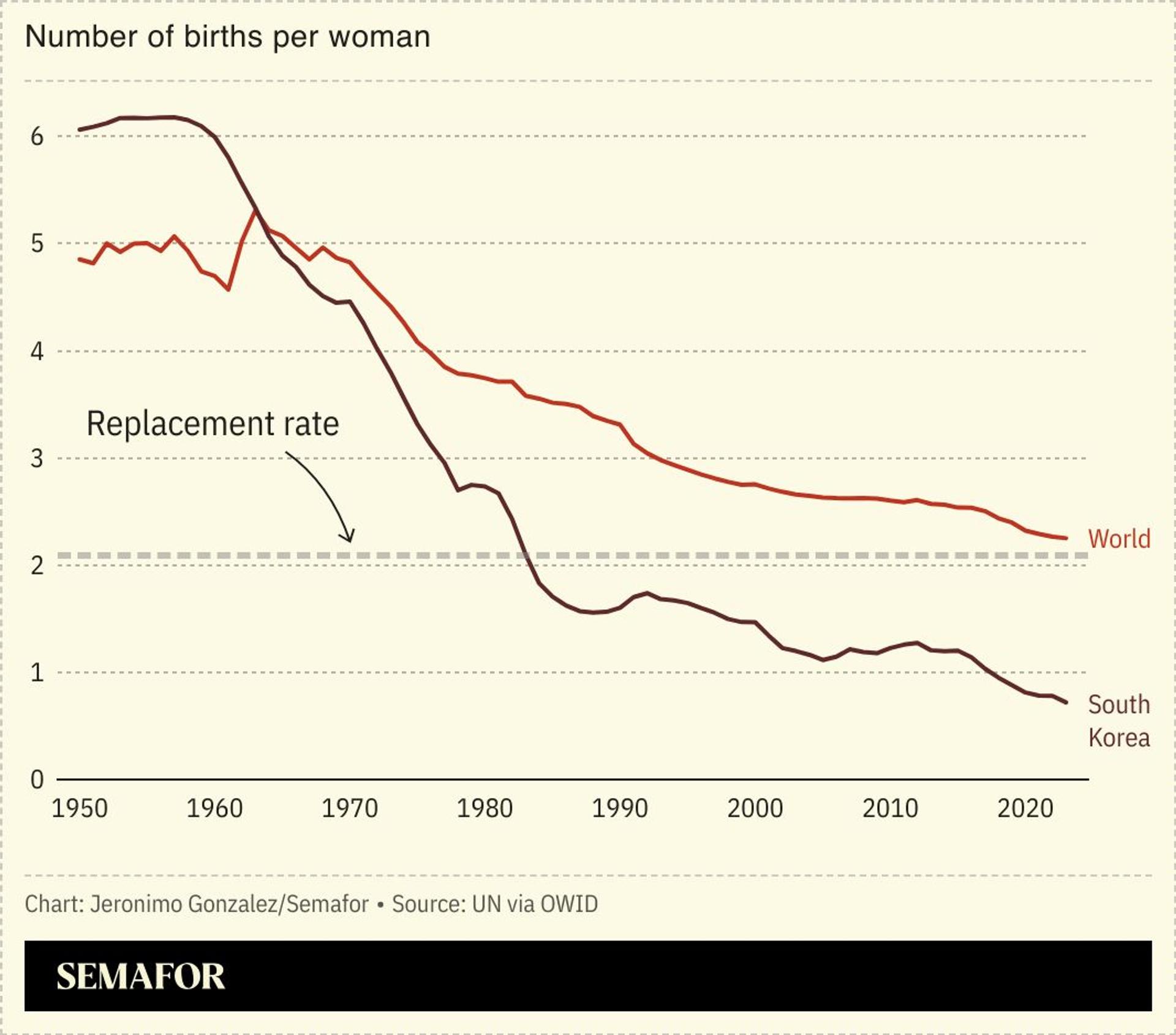

The average number of babies per woman increased from 0.72 in 2023 to 0.75 last year, still the lowest in the world and far below the replacement rate of 2.1.

SIGNALS

Birthrate supported by surge in marriages after government measures

A spike in marriages post-pandemic may be one factor driving the increase in births in South Korea, where few children are born to unmarried couples. The marriage rate jumped 14.9% in 2024 — the biggest increase since 1970 — Reuters reported, amid government measures to encourage young couples to get married and have children. More than 65% of single Koreans now say they want to get married, The Korea Times reported last October, though only just over half believe marriage is essential, according to a separate poll. “There was a change in social value, with more positive views about marriage and childbirth,” a Statistics Korea official said during a briefing Wednesday.

Unclear if fertility momentum will last, but population decline is not necessarily a disaster

Experts are unsure if the fertility momentum will persist: A South Korea-based sociologist told the Financial Times the rebound appeared to be a post-pandemic blip, warning that “things can get worse if the economy deteriorates.” Other countries have launched pronatalist drives with little success, and critics argue such initiatives often fail to tackle the structural reasons that make people increasingly reluctant to have children. Still, declining populations aren’t always economically disastrous: A Goldman Sachs report this week noted that in Japan, labor force participation is increasing despite a shrinking population as more women and older people working fuels an economic uptick, while companies that invest in labor-saving technologies improve productivity.