The News

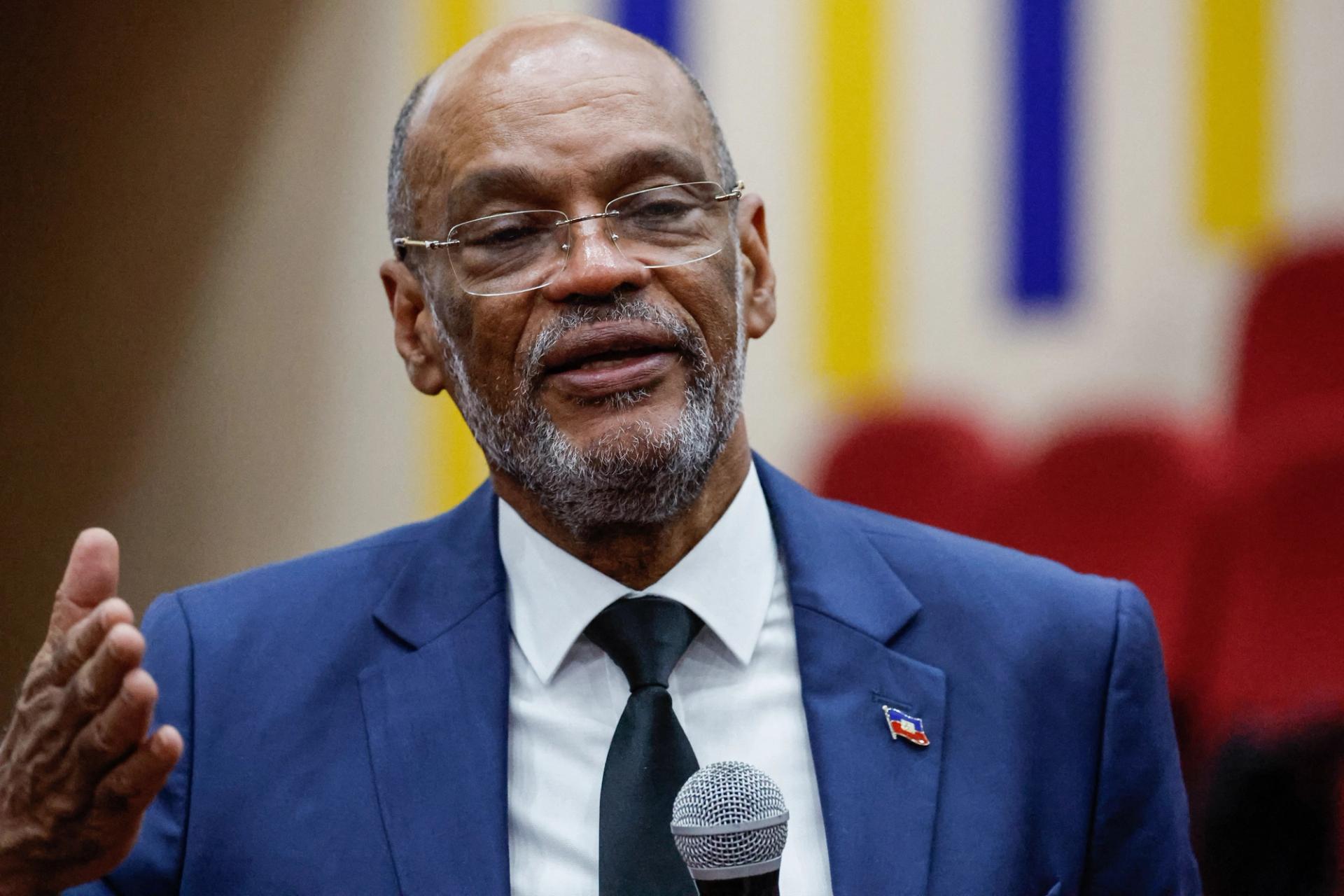

Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry agreed to resign after regional leaders held crisis talks in nearby Jamaica as violence mounted in his island nation.

U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken joined Monday’s meeting in Kingston, pledging an additional $100 million toward an international security mission, led by Kenya, to help quell the unrest in Haiti as well as $50 million in humanitarian aid.

This week, the U.S., European Union, and German embassies began evacuating diplomatic staff amid rising attacks by gangs, who control swaths of the country and most of the capital Port-au-Prince. Gang leaders have long demanded the unelected premier’s resignation, with one threatening “civil war” if Henry — who rose to power after the assassination of former leader Jovenel Moïse in 2021 — did not step down.

SIGNALS

A multinational security mission faces hurdles beyond funding

Haiti and Nairobi have agreed on a plan to deploy around 1,000 Kenyan police officers to the Caribbean island, as part of a U.N.-backed security mission, but the move is facing ongoing legal challenges in Kenya. The hurdles “make it increasingly look like either a bad plan, or one that is extremely difficult to implement,” Semafor’s Martin K.N Siele wrote last week. There are also historic reasons for a wariness to intervene in Haiti, the International Crisis Group wrote in January, pointing to the “sometimes tragic legacy” left by earlier foreign missions. Any security forces will have to counter potential collusion between Haitian police and gangs, while also learning how to distinguish civilians from gang members, it noted.

Foreign aid may not resolve the long-term problem

The history of aid in Haiti has raised questions about how any new funds will be used: “Money has served as a complicating lifeline — leaving the government with few incentives to carry out the institutional reforms necessary to rebuild the country, as it bets that every time the situation worsens, international governments will open their coffers,” The New York Times wrote in 2021. “So-called nation-building” efforts have instead eroded the state and doing more of it “won’t work,” one activist told the Times. NGOs such as the Red Cross have also faced a backlash in Haiti in the past, a 2015 ProPublica investigation found, with fund mismanagement and poor staffing choices wasting more than $500 million in disaster aid.

Haitian migrants to the United States will have limited options

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, more than 125,000 Haitian migrants arrived at American land and sea borders between October 2022 and July 2023, with many deported back to Port-au-Prince. The arrival of migrants escaping violence and poverty from Central America and Haiti has “intersected with a housing crisis that makes it nearly impossible for many new arrivals to find affordable shelter,” The Boston Globe reported. While Haitian migrants are eligible for a two-year humanitarian program that allows them to stay in the U.S. as long as they have a financial sponsor and pass a background check, the Miami Herald concluded that “options remain limited,” as an airport shutdown in Port-au-Prince has forced indefinite flight cancellations.