The Scoop

Investment firms CVC and HPS recently discussed a merger that would have created a $300 billion giant, a sign of the pressure on asset managers to bulk up and branch out as competition for money and deals intensifies.

The talks fell apart late last year and people close to both firms say they are moving ahead with their own plans to go public. But they show that even firms with size and success — CVC is a leader in European buyouts, HPS is a runaway hit in the fast-growing world of private credit — see the allure of the superstore model as fundraising gets tougher and investors concentrate their bets on a handful of managers.

Representatives for CVC and HPS declined to comment.

What once looked like an endless pool of cash chasing alternatives to publicly traded stocks and bonds is starting to run thin. As of January, about 14,500 separate funds were on the road seeking a combined $3.2 trillion, more than the value of every company listed on the London Stock Exchange, according to new data out this week from Bain, which concluded that there isn’t enough money in the world to go around.

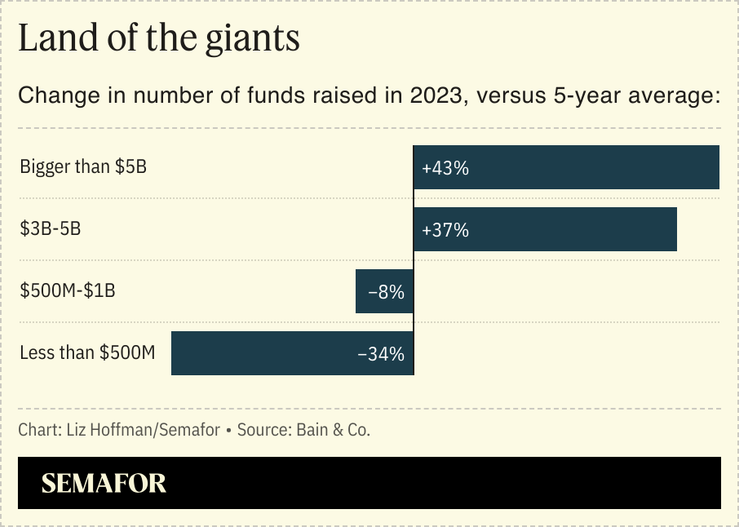

As in all contracting industries, the biggest players are winning. Investors are concentrating their money with larger managers, which can offer more products and discounted fees. First-time fund managers are finding few takers. The number of $5 billion-plus funds rose by a third in 2023 from a year earlier, while the number of sub-$500 million funds shrank by a similar amount, according to Bain.

“It is really only the large players that can withstand the forces reshaping the private markets industry,” David Layton, CEO of Partners Group, told the Financial Times last year.

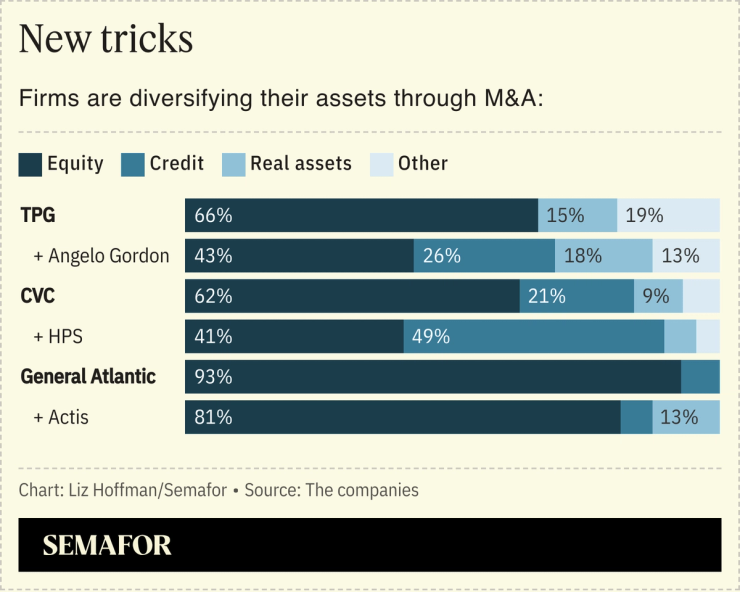

That’s driving firms to merge. TPG, one of the last big pure-play buyout shops, bought credit and real-estate shop Angelo Gordon last year. General Atlantic is buying infrastructure specialist Actis. Brookfield bought Deutsche Bank’s fund-stakes business. CVC has already dabbled, in September buying a Dutch infrastructure firm that owns data centers in Phoenix and a tram line in Belgium. BlackRock is buying infrastructure giant GIP and has signaled that it’s looking for a needle-moving takeover in credit. That list doesn’t mention the scramble among asset managers to buy up insurance companies.

A tie-up between CVC, which is trying to revive an IPO waylaid by a market rout in November, and HPS, whose own listing plans are among Wall Street’s worst-kept secrets, would have been more transformative than any of those deals.

CVC manages $200 billion and is best-known for well-executed, if fairly traditional, corporate buyouts in Europe. HPS was founded by a trio of Goldman Sachs alumni whose success in private credit has spawned copycats across Wall Street. A combined firm would have had $313 billion across equity, credit, infrastructure, and private-fund stakes — an investing superstore missing only the real-estate aisle, and it’s a generationally good time to be missing real estate.

In this article:

Liz’s view

Among the biggest alternative asset managers, only Blackstone and KKR can credibly claim to be true one-stop shops. Carlyle needs more infrastructure. Apollo needs real estate. Warbug Pincus and Advent are strictly buyouts, though they both seem fine with it.

When you talk to industry executives these days, they don’t talk about funds, they talk about “platforms.” Layton, the Partners Group CEO, invoked the phrase when he predicted that the roughly 11,000 existing private investment firms could shrink to 100 “next-generation platforms” over the next decade.

He means top-shelf fundraising and capital-markets teams figuring out how to find and optimize every dollar, and operating teams figuring out how to fine-tune every asset. The image of private equity has been slow to change from its early wildcatter days, but the industry is mature, and it’s doing what mature industries do when growth slows — becoming a grinding ground game of execution and scale, where the big get bigger and the small don’t survive.

Room for Disagreement

Buyers in asset-management deals aren’t actually buying the assets; those belong to investors like pension funds. They’re buying the people, and the history of M&A in this industry is full of cautionary tales. Reuters’ Peter Thal Larsen wrote last year:

“Buyers typically pay twice: first to acquire the target’s shares, and then again to lock in key employees. Revenue tends to shrivel as rivals snap up clients, while clashing cultures can lead to disaffection and defections.”

Notable

- Antitrust regulators, take note: “While investors may be spared the tyranny of choice that comes with a saturated market, fewer players will be bad for competition and may eventually expose LPs to a higher fee burden and less diversification,” PitchBook’s Andrew Woodman writes.