The Scene

Bill Demchak is the CEO of PNC, the eighth-biggest bank in America. It’s one of a handful of “super-regional” banks that are uncomfortably stuck between their provincial roots and competition from giants like JPMorgan, where Demchak started his career.

We spoke on the day that an investor group led by former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin stepped in to rescue another teetering bank, about the echoes of March 2023 and how PNC can compete in an industry where size is everything. The conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A

What were you doing a year ago?

I was on a conference call with a bunch of other bank CEOs trying to figure out how to put deposits into First Republic to keep it from failing.

Another bank, New York Community Bank, just got rescued. Is this a one-off or the start of another round of problems?

I don’t know NYCB all that well, but their problems aren’t new. What’s new is a new regulator looking at old books. There was a big shock of, hey, everything’s fine, oops, no it isn’t, and everything goes downhill fast because people have last year fresh in their minds. They’ve attracted new capital, which is smart capital by all accounts. And my guess is somebody with a calm head went in and looked at their books and said, ‘This isn’t terrible, we’ll buy it cheap and we’ll make money.’

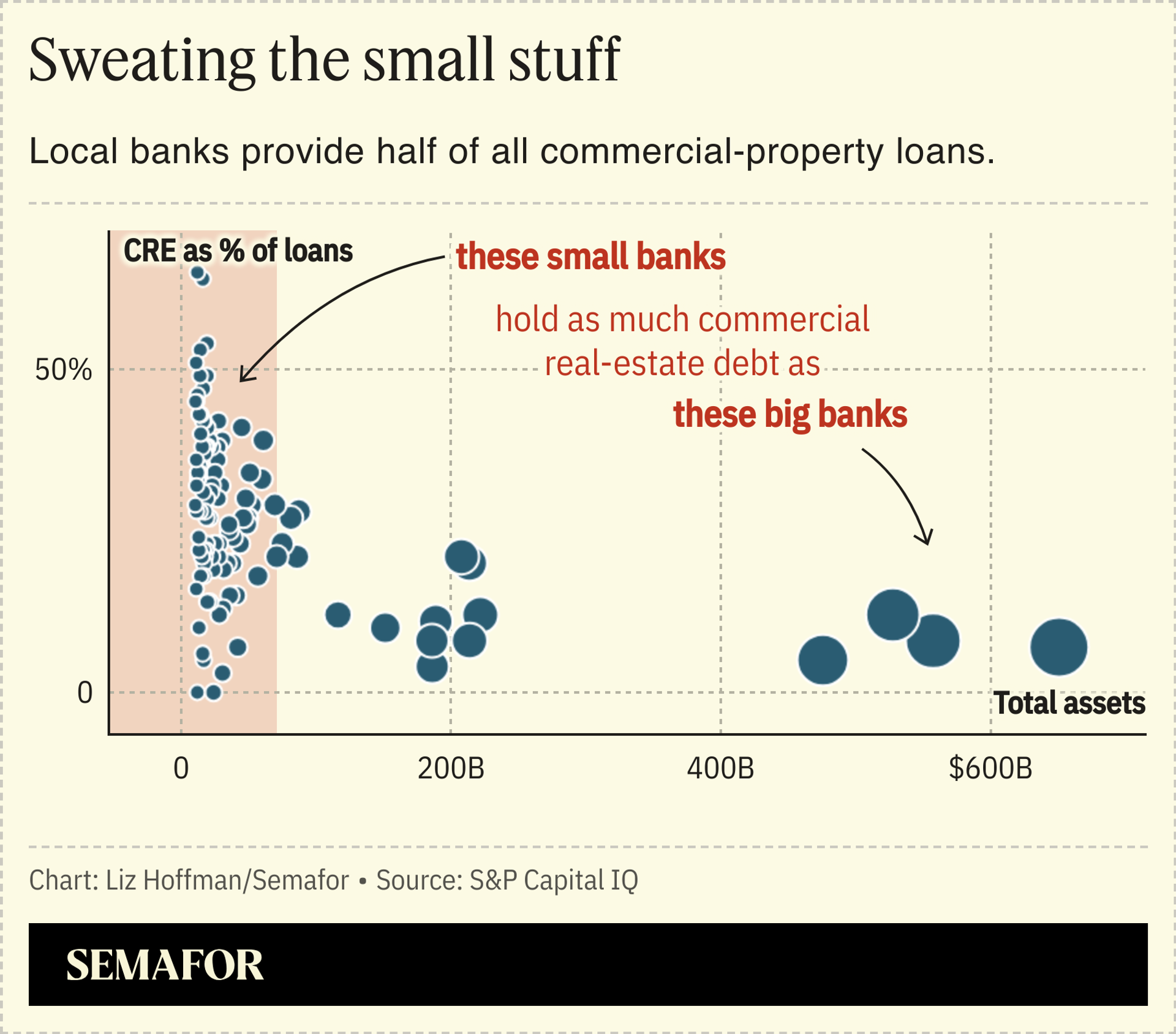

So I don’t think it’s a here-we-go-again moment. Real estate is going to be a problem, but not a systemic shock.

Have we seen the last midsized bank to fail?

My guess is that hundreds of small banks will default because of real estate. My guess is also that you won’t have heard of most of them. They’ll be resolved through mergers by the FDIC and it won’t even make headlines.

PNC bid for First Republic last spring, and I don’t think it’s a secret that you weren’t thrilled with how the process was run. Would you participate again?

We tried to do something that was economically attractive for our shareholders, that would grow the franchise, and help the country out of a bind. Win, win, win. In the process, we would have been seen as a safe institution that had regulators’ blessing to grow larger. In that way, JPMorgan getting First Republic was somewhat unfortunate because [the government] almost said the opposite — that we can only give it to a giant bank. That was disappointing.

I know they’re working on improving a process that was, probably by their own admission, a bit of a mess. In their defense, they hadn’t been put to the test in years. The skill sets and the playbooks were probably a little stale, and there were new players. In hindsight, it’s easy to say, ‘why did you do it that way? you could have saved the [deposit insurance] fund a lot of money,’ which is true. But nobody knew which way was up and there wasn’t a lot of time to figure out the right answer.

Was there ever a moment when you thought PNC was in trouble?

No. We had been pretty neutral to the whole rate-rise thing. We got grief, probably for five years, because we had so much cash sitting at the Fed, doing nothing. [Investors] would ask when we were going to deploy it. But do I really care if I make an extra 1% on our cash, against the risk of that going sideways? So we never did.

I remember seeing you a few years ago, just after you bought BBVA’s U.S. business for $12 billion and I asked if you were done doing M&A. I think you said, “no, but that’s not by choice.” The sense was that PNC was as big as regulators were going to allow. Has the past year changed that?

I think so. Whether they meant to or not, last March regulators basically said that large banks are safe and smaller banks aren’t. You were either a G-SIFI, or you were a regional bank. And I don’t think we go back to a world where a reasonable-sized corporation says ‘I’m going to have a regional as my lead bank.’

So the need for scale is greater than it’s ever been, and I think regulators see it. I think they want to create challenger banks to the big two or big three. I hope I’m right. But I’m also more willing to push on that than perhaps I was two years ago.

How big do you think you have to be before people don’t think of you as a regional bank anymore?

It’s not a size thing. We need to have scale in our newer markets [including Dallas, Denver, and Miami] approaching the scale we have in our legacy markets [in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest]. If we did that, mathematically, we’d probably double in size.

But it’s more about having a ubiquitous brand, having everybody know who we are, being able to keep our customers when they move from one city to the other, and having scale in the businesses we choose to be in. We don’t have to be BofA or Wells Fargo, but we have to have scale in the same businesses we compete with them in.

Should we expect to see you try to pull off a big deal in the next year?

Probably not. There’s no hidden message in what I’m talking about. The need for scale is real. We’re prepared to go it alone; we’re not afraid of investment. If an economic opportunity shows up that allows us to accelerate that, terrific. But I’m not going to force it.

Discover is being sold to Capital One. Would you have considered that deal?

It’s not what we’re good at. We’re good at commercial loans. If our customers want a credit card, we’ll give them one, but we’re not someone who can go in and fix what, by all appearances, is a broken consumer-credit engine. By the way, I think Capital One is.

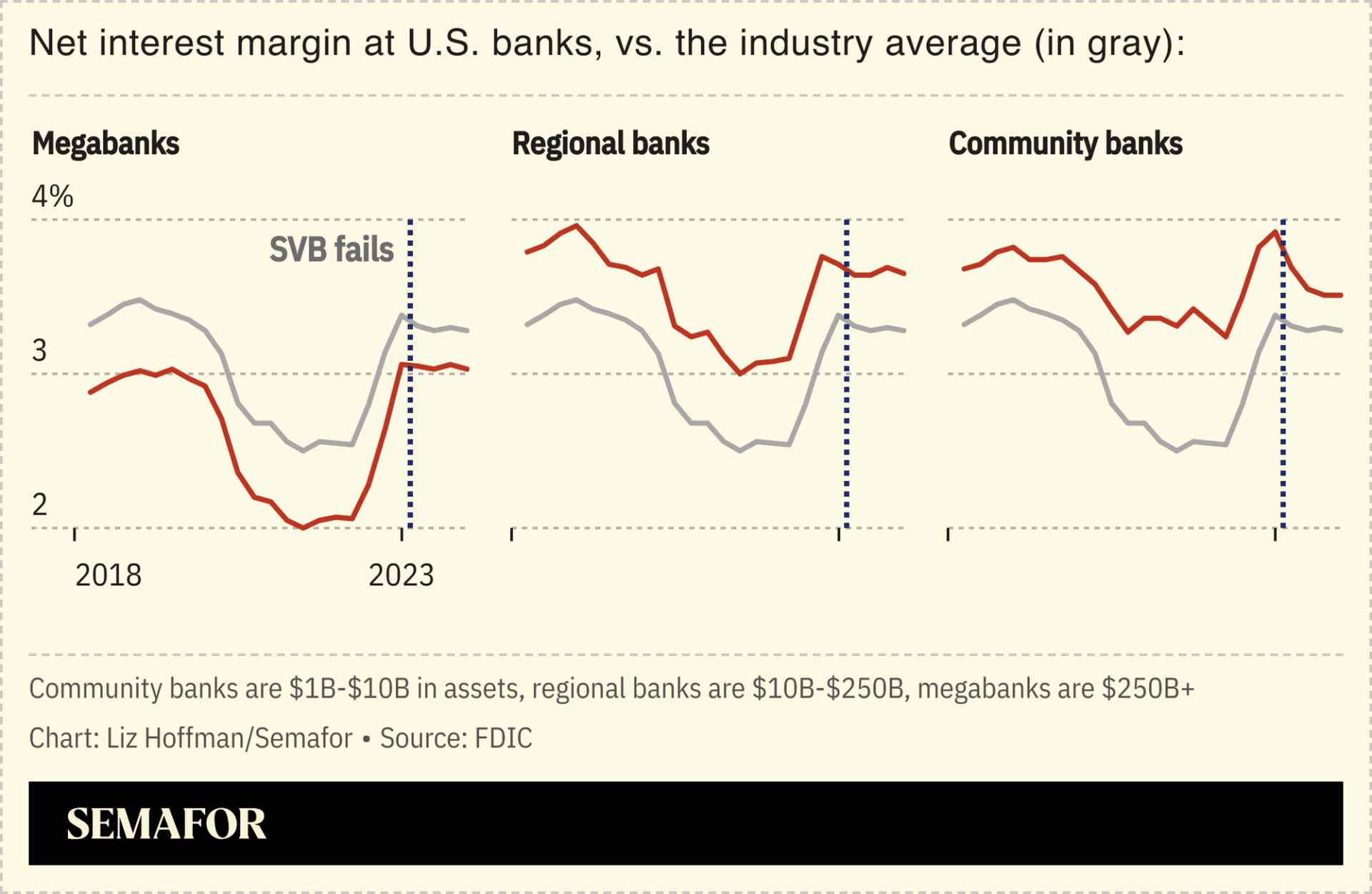

I’ve been surprised that, for all the talk of collapsing margins and banks having to pay more for deposits, profitability hasn’t tanked. Why not?

There’s probably a little more to come there, especially at smaller banks that have continued pressure to fund themselves at market.

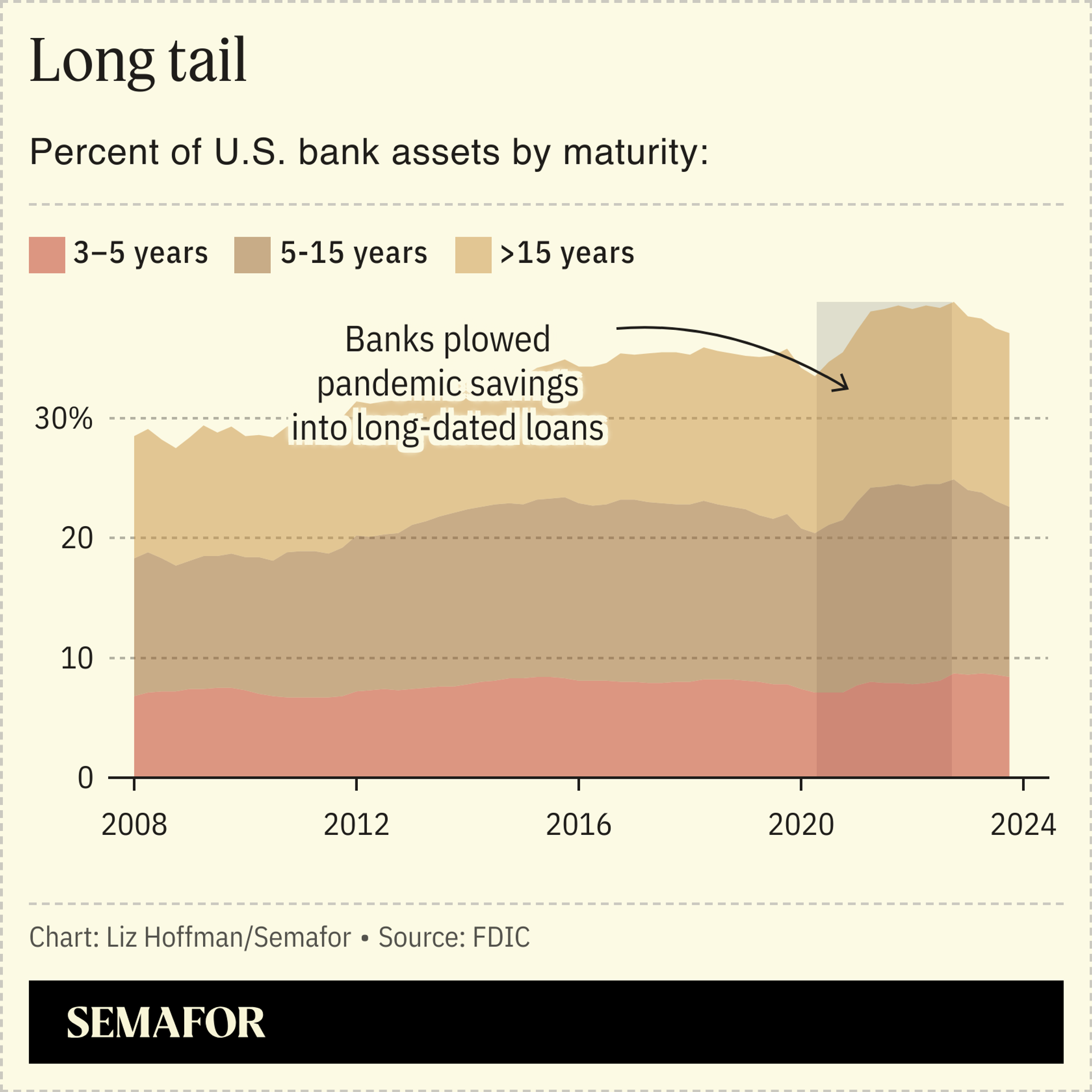

But the thing to remember is the duration of your loan book. If I own a 2% Treasury that matures, I’m going to reinvest it at 4.5%. If your portfolio averages four years, which ours did, you get all of that bump in the next four years. If your portfolio is a 30-year portfolio, which Silicon Valley’s was, it takes 30 years to get that benefit.

You’re going to see some margins continuing to go down, others will trough, and then it’s going to be a question of who can climb the fastest, which will be entirely a function of how long-dated their fixed-rate assets are.

Do we have too many banks?

The structure of the banking system today — continued pressure on fees, cost of regulation, cost of technology, fraud and cyber — has caused a big swath of the U.S. banking system, in my view, to be untenable. True community banks, many of them family-owned, I think serve an important purpose and will be around forever. But the midcap banks that were $5 billion balance sheet banks and tried to be heroes and grow to $50 billion find themselves in a really uncomfortable place.

You have new ads calling PNC “brilliantly boring.” Regulators would certainly like banks to be more boring, and investors have shown a preference for steadier businesses.

We certainly didn’t come up with the ad campaign to play to regulators. We put it out there purposefully to be noticed. We need to build scale and awareness in these new markets, so if you’re sitting there and scratching your head and saying, ‘I wonder what the hell they meant by this, then I’ve succeeded.’

For our shareholders, boring is that we’ve hit our earnings guidance 40 quarters in a row. We’re the lowest in credit charge-offs. We always seem to have a little bit less of whatever the bad thing is that everyone is worried about. For our customers, it’s boring in the delivery. You shouldn’t have to think about your bank, it should just work. We shouldn’t be scaring the hell out of you.

It sounds like the Fed is rethinking its latest proposed bank rules.

Powell’s testimony was encouraging. None of it surprised me, but the visceral reaction that had come in from both Democrats and Republicans on the original Basel 3 Endgame proposal, almost certainly will cause substantial changes to be made. I think it needs those. Not so much because I think capital requirements have gone too high — you can have a separate argument about that — but it just didn’t follow risk-based logic. It was like they said, ‘We need a rule that solves to this number, so we’re going to just shove a bunch of stuff in here.’ That leads to really bad outcomes.