The Facts

U.S. banks shifted hundreds of billions of dollars worth of securities into the equivalent of a sock drawer in 2022, hoping to avoid acknowledging that they were hopelessly underwater in a world where money wasn’t free.

Loans made in 2020 or 2021 got less valuable as the Federal Reserve raised rates to battle inflation. So lenders took advantage of accounting rules to avoid taking billions in losses, regulatory filings show.

In this article:

Know More

When a bank makes a loan, accountants assign it one of two labels. “Held to maturity” loans don’t have to be valued daily, since the bank isn’t planning to sell them. But “available for sale” loans do, and their gains and losses have to be disclosed.

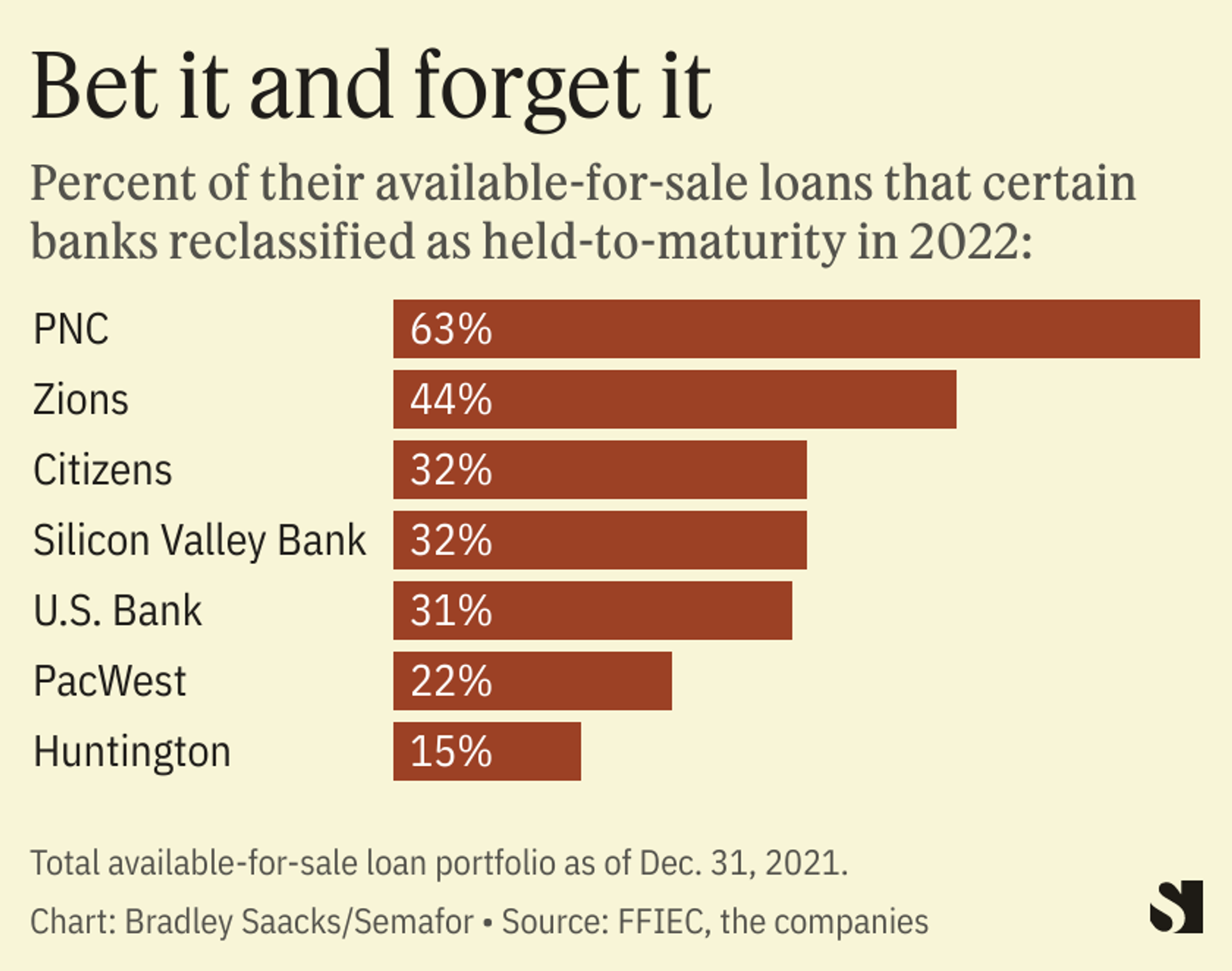

American banks sold or reclassified almost $700 billion worth of securities last year, avoiding billions of dollars of paper losses.

SVB shifted $8.8 billion, or about a third of its available-for-sale portfolio, into held-to-maturity status last year, filings show. PNC Bank reclassified $82.7 billion in mostly Treasury bonds and mortgage bonds, which saved it from having to recognize $5 billion in paper losses.

Liz’s view

There are good reasons for the accounting treatment. Slapping daily valuations on assets intended to be held, more or less, forever injects volatility into situations where it doesn’t need to be.

The problem, though, is an SVB-like situation, where a deposit run forces banks to sell those assets. The losses are crystallized, stunning investors and, in SVB’s case, made the firm insolvent.

Room for Disagreement

This might be a challenge for accountants, as much as for regulators and supervisors, says João Granja, a finance professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

To defend the sock-drawer treatment of securities, companies need to have

“not just the intention, but the ability” to hold them forever, Granja said. That means pressure-testing the stickiness of their funding.

The Fed’s former vice chair of supervision, Randal Quarles, told me last week that the SVB collapse requires a rethinking of how retail depositors will behave, for starters.)