The Scoop

A year after panic swept through America’s banking system, the big winner is a company you’ve never heard of.

IntraFi is a marketplace where banks buy, sell, and swap deposits. After the failure of Silicon Valley Bank woke customers up to the possibility that their money wasn’t safe, they became choosier about where they kept it. Deposits suddenly became a valuable commodity.

Enter IntraFi, which was founded in 2002 by three former bank regulators who saw an arbitrage play in how U.S. banking regulations work.

The government guarantees deposits up to $250,000 per account. IntraFi splits big customer deposits across several banks to keep each individual account under that limit, maximizing federal insurance. It also makes about a quarter of its money by brokering one-way transactions, where a bank with deposits to spare sells them to one that’s running short. IntraFi takes a small cut each time.

The privately held company’s revenue jumped 62% last year, and has more than doubled since 2021, according to internal financials reviewed by Semafor. It booked $415 million in profits on $525 million in revenue in 2023 — an 80% margin.

It has few competitors, all of them tiny. Except for some technological upkeep, incremental costs are near zero. Every new dollar that flows through IntraFi’s digital pipes, which connect two-thirds of U.S. banks, is more profitable than the last one. The company’s private-equity owners, Warburg Pincus and Blackstone, have paid themselves $747 million in dividends since December.

“IntraFi’s strong financial position enables us to make the type of technology, security and other investments necessary in today’s environment,” a company spokesman said, declining to comment on the financial figures. “We provide a unique and valuable service for a fair price.”

He said that IntraFi has never raised its prices — it charges 12.5 cents for each $10,000 that moves — and notes that other financial networks have high profit margins, too. (For comparison, Visa’s was 70% last year and Mastercard’s was 58%.)

In this article:

Know More

When interest rates were low, customers didn’t pay much attention to their cash. Banks were happy to take the free money and lend it out at higher rates. Uninsured deposits at U.S. banks grew from $1.5 trillion in 2011 to $7.5 trillion by the start of 2023.

That unraveled last spring, when Silicon Valley Bank, where 96% of deposits were uninsured, collapsed. Customers moved billions of dollars to giants that seemed safer, like JPMorgan and Bank of America.

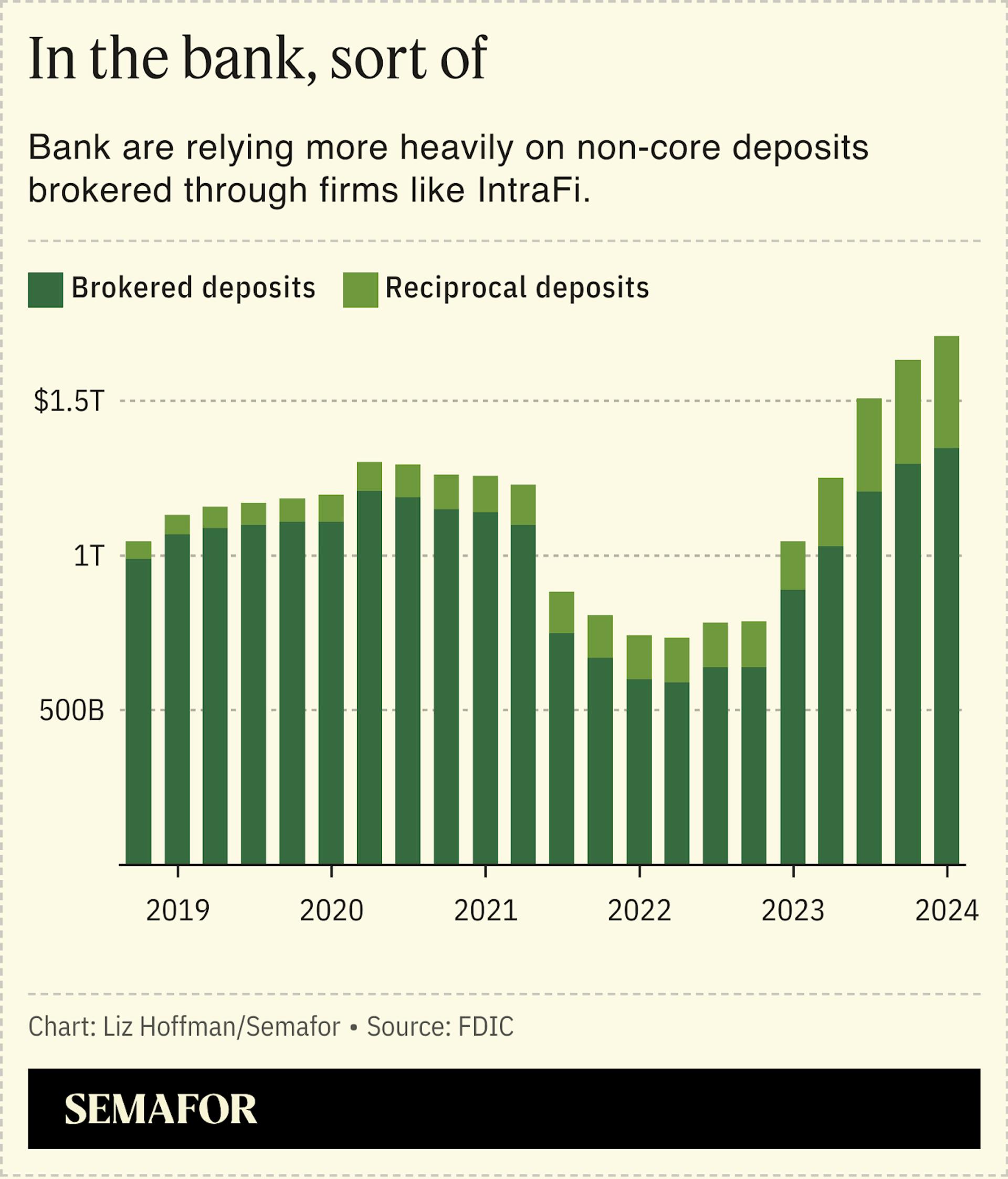

To reassure them, midsized banks used IntraFi to divvy up deposits above the $250,000 insurance cap. These “reciprocal deposits” rose from $90 billion just before the pandemic to $300 billion by the middle of 2023, according to Federal Reserve data.

They also started buying deposits outright to replace money that was leaving. Those “brokered deposits” doubled between mid-2022 and mid-2023, and have continued to grow. All in, banks today have $1.7 trillion of deposits — about 10% of their total — that aren’t quite theirs, nearly all of it enabled by IntraFi.

These deposits aren’t as sticky as, for example, savings accounts where customers deposit their paychecks. They are, to varying degrees, considered hot money by the Federal Reserve, which penalize banks that rely too heavily on them.

IntraFi has been trying to change that perception, particularly when it comes to reciprocal deposits. A postmortem report, prepared confidentially last spring for regulators, showed that those deposits did not run and in fact were stickier at the most troubled banks than their core deposits, which include individual savings and corporate operating accounts opened inside branches.

Leader Bank, a $4.5 billion lender outside Boston, started using IntraFi about five years ago to handle its biggest accounts, “so we were already up and roaring” by last spring, said its president, Jay Tuli. His pitch to clients who asked to move their money to big banks: “We’re healthy, we’re strong, but you don’t even need to believe us because we’re going to put you on IntraFi,” he said in an interview. “Here’s an actual guarantee, versus the implicit ‘too big to fail’ argument for big banks.”

About a third of his $3.7 billion of deposits at the end of last year came from IntraFi, about $700 million of them swapped with other banks and $500 million brokered deposits bought outright, regulatory filings show.

Liz’s view

The good news: IntraFi may single-handedly be keeping hundreds of small banks in business. By spreading deposits around, they reduce the risk of a bank run because customers will know their cash is safe.

The bad news: IntraFi may single-handedly be keeping hundreds of small banks in business. America has 4,700 banks, which is way too many, and the lesson of last spring — that big banks are safe and small ones aren’t — was directionally true, even if it lacked nuance. Smaller banks simply can’t afford to make the same investments in technology, cybersecurity, and compliance that big banks can. They have fewer sources of funding, which makes them more vulnerable to a run. And they are not Too Big To Fail. They fail all the time.

It’s not a coincidence that the heaviest users of IntraFi’s products last spring were midsized banks, some of which had real problems with upside-down balance sheets, some of which just got caught up in the panic.

First Republic lost two-thirds of its core deposits during the first quarter of 2023, and stanched the bleeding with $3.5 billion in reciprocal deposits and $2 billion in brokered deposits. Utah-based Zions Bancorp lost $9 billion in core deposits and bought $7.5 billion in the market. As it was teetering, New York Community Bank bought deposits from IntraFi, a person familiar with the matter said.

First Republic would have failed faster without IntraFi, and others may not have survived at all. That’s helpful in a crisis, but there’s a reason that regulators treat core deposits to be the safest. The heaviest users of IntraFi’s products are “precisely the banks that have been deemed by the market as being the riskiest,” Bill Demchak, chief executive of PNC, the sixth-biggest U.S. bank by deposits, told me recently.

IntraFi is essentially selling insurance above and beyond what the FDIC offers. But it’s a weird insurance policy. IntraFi doesn’t pay out in the event of a failure. The fees it collects aren’t policy premiums that are pooled and invested conservatively to cover future payouts. They’re profits, collected by two private-equity firms.

We end up paying. The FDIC is collecting $16 billion from banks to recoup the cost of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure, and several have warned they will simply pass the costs on to customers. It would be nice if we were at least making money selling the policies. Matt Stoller, head of the left-leaning think tank American Economic Liberties Project, thinks the FDIC should offer this service itself, and let those profits flow to the taxpayer.

IntraFi has essentially privatized a public asset: the quirks of America’s banking system. If regulators raised the $250,000 cap, which they considered last spring, IntraFi would make a lot less money.

IntraFi increased its lobbying efforts in 2023 as regulators were weighing whether to suspend that cap and essentially issue a blanket guarantee for all deposits. (“After the regional bank failures of last year, a number of lawmakers reached out to us and our government relations firms to find out more about reciprocal deposits,” IntraFi said in a statement, adding that the company mostly defers to industry trade groups on legislation.)

And if there were 100 banks instead of 4,700, it would make sense for a competitor to come in, build a competing network, and undercut IntraFi. Instead, it has the rarest and most valuable thing in business: a legal monopoly.

Room for Disagreement

“Policymakers have come to underappreciate the importance of mid-sized banks to the economy,” writes Eugene Ludwig, a former top banking regulator and one of IntraFi’s co-founders (It was called Promontory Interfinancial Network back then and former Fed Vice Chair Alan Blinder is also a co-founder.). The government’s post-2008 implied backstop of the biggest banks has created a snowballing advantage that was exacerbated by last spring’s turmoil.

A marketplace for deposits can level that playing field, and not just by smoothing out funding costs. Small banks rely on local governments or foundations that keep millions of dollars in their accounts and that want their cash to be lent out in their communities, a guarantee they can’t get from a national bank. Being able to insure those accounts through IntraFi keeps them in the community.

Notable

- What guarantee? FDIC Chair Marty Gruenberg said this week that the agency wouldn’t hesitate to seize a “too big to fail” bank. “I would put JPMorgan … into a resolution process,” he told the FT.