The Scoop

The Federal Reserve is resisting pressure from the White House and Washington to spur big banks to buy more Treasury bonds, a reluctance that could further shake an unnerved market for US debt.

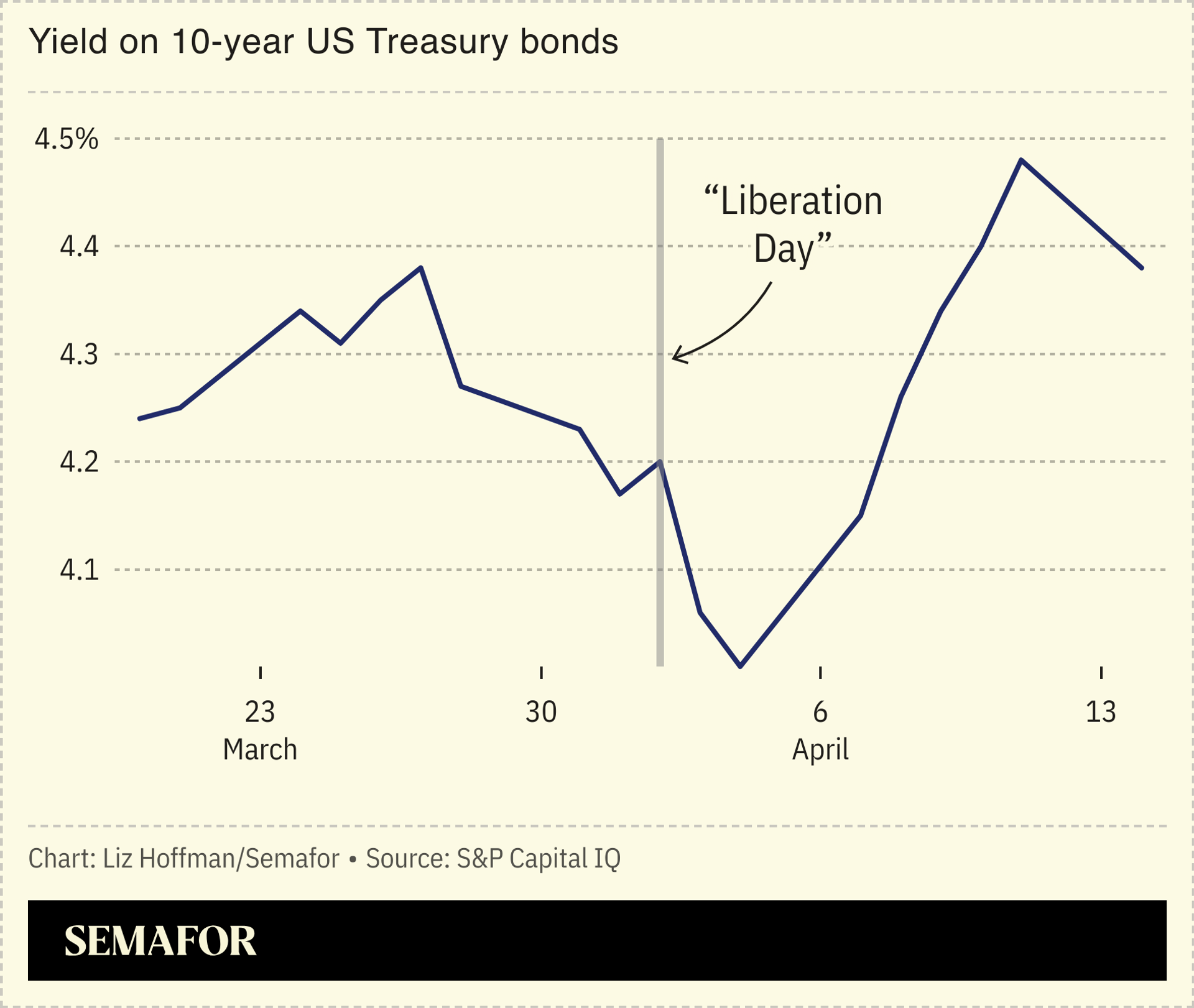

Wild swings in Treasury prices forced President Donald Trump to reverse course on his sweeping tariffs, and investors remain spooked even after his backtrack. Higher yields on government bonds are a sign of stress and eroding faith in the American government to pay its bills.

Still, the Fed isn’t accelerating regulatory changes that would encourage banks to load up on government debt, people familiar with the matter said, even though Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon both support the idea. Tweaks to rules that currently penalize banks for holding big slugs of Treasury bonds are instead winding their way through a painstaking internal process that could take months, the people said.

“These rules effectively discourage banks from acting as intermediaries in the financial markets – and this would be particularly painful at precisely the wrong time: when markets get volatile,” Dimon wrote in his annual letter published last week.

Tweaking them could bring billions of dollars of buying firepower into a market full of sellers. Boston Fed President Susan Collins told the Financial Times last week that the central bank was “absolutely” prepared to intervene if necessary, remarks that some investors saw as proof the Fed was ready to step in.

The Fed has been working on a proposal since February but has no plans to rush out a final rule, in part because it’s wary of being seen as panicking — or worse, bailing out the administration or hedge funds that have been heavy sellers. The current plan is to float the changes later this spring or summer through the normal regulatory process, the people said.

There’s no sign that the Treasury market is broken, as trading has been orderly and auctions of fresh bonds have gone well. But investors demanding higher yields to lend to the US government is a worrying sign and makes other types of borrowing, like mortgages and car loans, more expensive.

In this article:

Know More

“The safest asset in the country, US Treasurys, are not treated as such,” Bessent said at the Economic Club of New York last month. “I’m not here today making a specific policy announcement, only to make the point that rigorous analysis must be applied to these regulations.”

Michelle Bowman, the Fed’s vice chair of supervision, has also called for easing regulations on banks’ ability to own Treasury bonds, as have some congressional Republicans.

Liz’s view

Stepping in would be politically dicey. One likely cause of the bond selloff is hedge funds unwinding popular Treasury trades, and direct intervention by the Fed would invite criticism that it is bailing out Wall Street. The Fed could buy Treasury bonds itself, but has been shrinking its holdings since 2022 and is reluctant to grow its balance sheet.

That leaves big banks as the obvious knife-catchers. And it would seemingly cost the Fed little to move up a change it plans to make eventually. But there is a queasy circular illogic in the central bank declaring US Treasury bonds a risk-free asset at the exact moment the market has decided they aren’t.

Notable

- The chatter alone is worrying enough: “When senior politicians start talking about technicalities of obscure financial regulations on mainstream TV you can be sure something is up,” writes Bloomberg columnist Paul Davies.

Gina Chon contributed reporting.