The News

The biggest U.S. banks mostly shrugged off the recent turmoil among regional rivals, but a fight is brewing in Washington over whether they are taking too many risks with customers’ cash.

JPMorgan, Citigroup and Wells Fargo all posted solid earnings for the first three months of the year, a stretch that included the failure of two smaller banks and the near collapse of a third.

Overall, the biggest banks are winners so far, scooping up cash from panicked depositors at the country’s rickety regional lenders. (Two outliers: Bank of America, which lost $20 billion in deposits in the quarter, and Goldman Sachs, which is extricating itself from an expensive folly in consumer banking and posted a $470 million loss as it dumped loans in that business.)

Progressive policymakers are pushing regulators to toughen rules requiring banks to hold more capital against the loans and investments they make. Those requirements were rolled back under the Trump administration for all but the biggest banks, and everyone from Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren to top Biden economic adviser Lael Brainard have been on some version of I-told-you-so tours in recent weeks.

Even the Federal Reserve’s top supervision cop, Michael Barr, told a Senate hearing last month that stress tests that are supposed to monitor banks’ health have been too backward-looking and failed to test for the right things.

“Banking should be boring,” Warren said recently. “Banking is about making sure the money’s there.”

Liz’s view

Yes, the money should be there in a general sense. When you go to the ATM, check your balance, and ask for $100, it should spit out $100.

But the whole point of banks is that the money isn’t there. To state the obvious, no bank has enough money in its vaults to pay out its depositors, nor should it. Banks exist to transform risk — to take safe liabilities like depositors’ cash and turn it into longer, riskier assets like mortgages or buyout loans or financing for new solar farms or skyscrapers.

They do that through an ideally careful process of matching. They try to lock up the money they owe people (mostly depositors and bondholders) for roughly as long as the money that people (mostly borrowers and issuers of securities, including the U.S. government) owe them. Some banks do that better than others — Silicon Valley Bank did it supremely, intentionally badly — but that’s the business. Risk is a feature, not a bug.

When I was just starting out on the banking beat, I wrote what remains one of my favorite stories. Goldman Sachs had lent one of its billionaire clients a bunch of money to buy a yacht, the billionaire had defaulted on the loan, and then Goldman Sachs owned a yacht, and one in a fairly severe state of disrepair.

The lede of the story was that you’d expect a bank like Goldman to own lots of vanilla things stocks and bonds but now it owned a yacht, and that was weird and fun.

But I was wrong. (Remember, I was new on the beat.) Banks exist to own secured claims on exotic things like yachts. It’s actually weirder that they own lots of liquid things like Treasury bills and mortgage bonds. We can all own Treasury bonds, and so we don’t need banks to own them for us. We can’t all make billionaire yacht loans, or provide financing for solar farms and skyscrapers and leveraged buyouts. We need banks to do it.

The tendency of banks to load up on liquid assets is a relatively recent phenomenon, coming out of the 2008 crisis. The lesson then was that banks owned too much risky, illiquid stuff and not enough safe, boring stuff, so we made them more boring through things like Dodd-Frank and stress tests.

Before the crash, loans made up about 80% of the biggest banks’ tangible assets, setting aside cash and some other smaller-ticket items, according to FDIC data. Today that figure is about 65%, and the gap has been filled mostly by Treasury bonds and government-backed mortgage bonds — among the most liquid assets on earth.

Today’s banks may not be boring enough for progressives, but they’re a lot more boring than they used to be. Regulators can force them to keep a dollar in cash for each dollar they owe people, but then that’s not a bank, it’s a mattress.

Room for Disagreement

Warren told CNBC last month that when banks take risks, they often get into trouble. She has proposed a bill to undo the Trump administration’s loosening of regulation for medium-sized banks, and another to claw back pay from executives if their banks have to be rescued.

“I really want to say to bank CEOs, if you’re the kind of guy or gal who wants to roll those dice and take big risks, don’t go into banking,” Warren said. “Banks should absolutely be able to make profits, but when banks load up on risks, they put depositors at risk, they put small businesses at risk, and ultimately … they put our whole economy at risk.”

The View From Minneapolis

U.S. Bank has been a model lender for years, avoiding expensive screw-ups and embodying the kind of middle-America, small-business banking that politicians love.

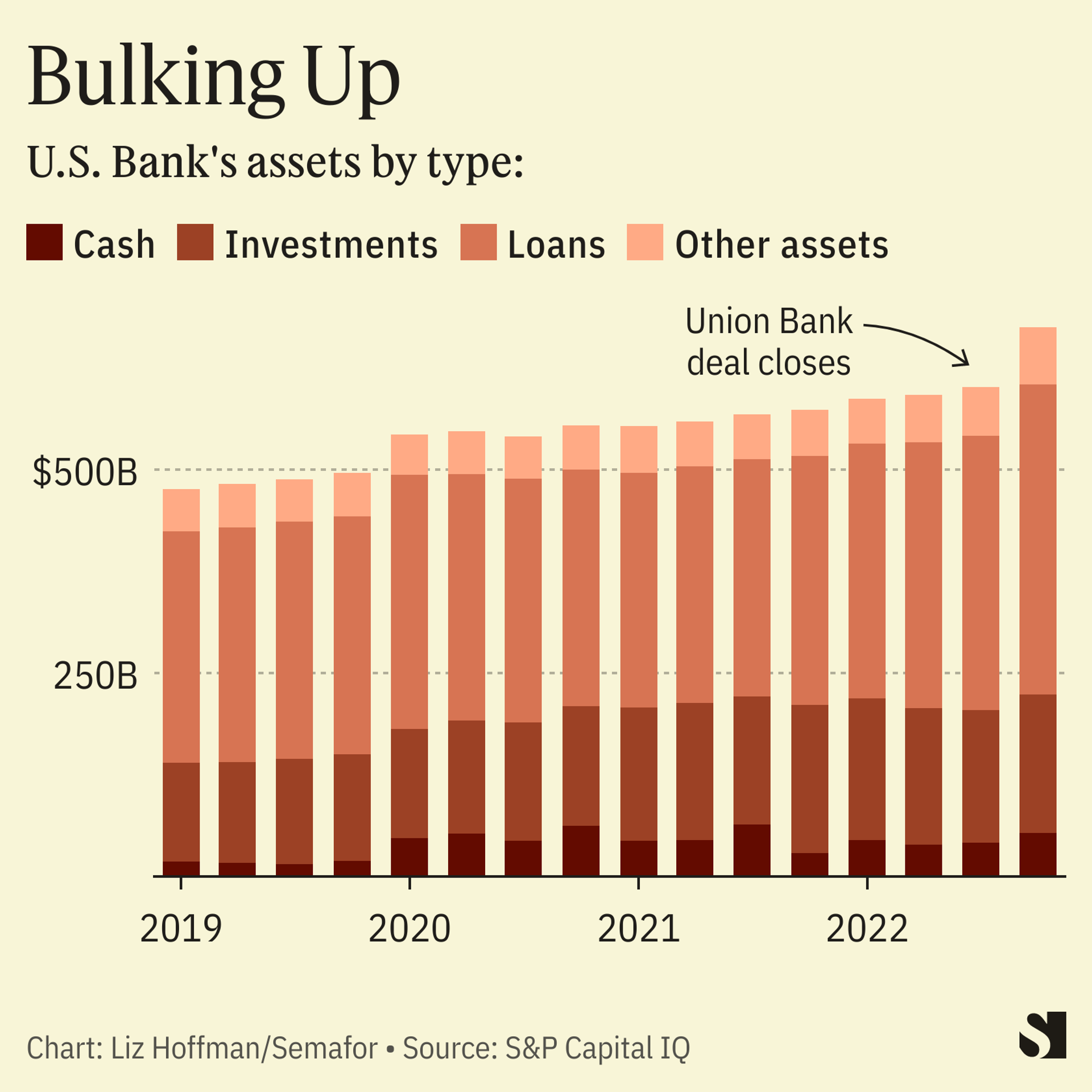

But a hedge fund now says it’s dramatically undercapitalized and will have to raise new money, cut its dividend or slow its rapid growth, which has led to a 36% increase in its assets since 2019. HoldCo Asset Management’s 84-slide presentation warns that U.S. Bank is ill-prepared for a new wave of regulation and could need to raise billions of dollars in fresh capital to meet minimum requirements.

HoldCo, which is betting against U.S. Bank’s shares, has some credibility here: It identified weaknesses at Silicon Valley Bank as early as 2021, arguing that its shares were overvalued and heading for a reset. (It didn’t finger the flightiness of SVB’s deposit funding, but did flag its huge investment portfolio as a source of potential problems.)

U.S. Bank has grown from under $500 billion of assets to $674 billion as of year-end, and is now approaching a $700 billion threshold that will bring additional regulation and force it to hold more capital against its loans and investments. Even if it cools its growth or sells some assets to stay below that cap, it agreed with the Fed as part of its takeover last year of Union Bank to be subjected to those higher rules by the end of next year.

The bank has paused stock buybacks to grow capital and expects to be comfortably above the new minimum by the end of next year. HoldCo thinks it won’t be enough. “Real actions are required before a recession – potentially at the same time as high rates – makes capital raises more difficult,” the fund said in its presentation.

A spokesman for U.S. Bank didn’t comment, citing its earnings release tomorrow.

Notable

- Barr told senators that the Fed’s review of SVB’s collapse will include an evaluation of its own rules and supervision.