The Scene

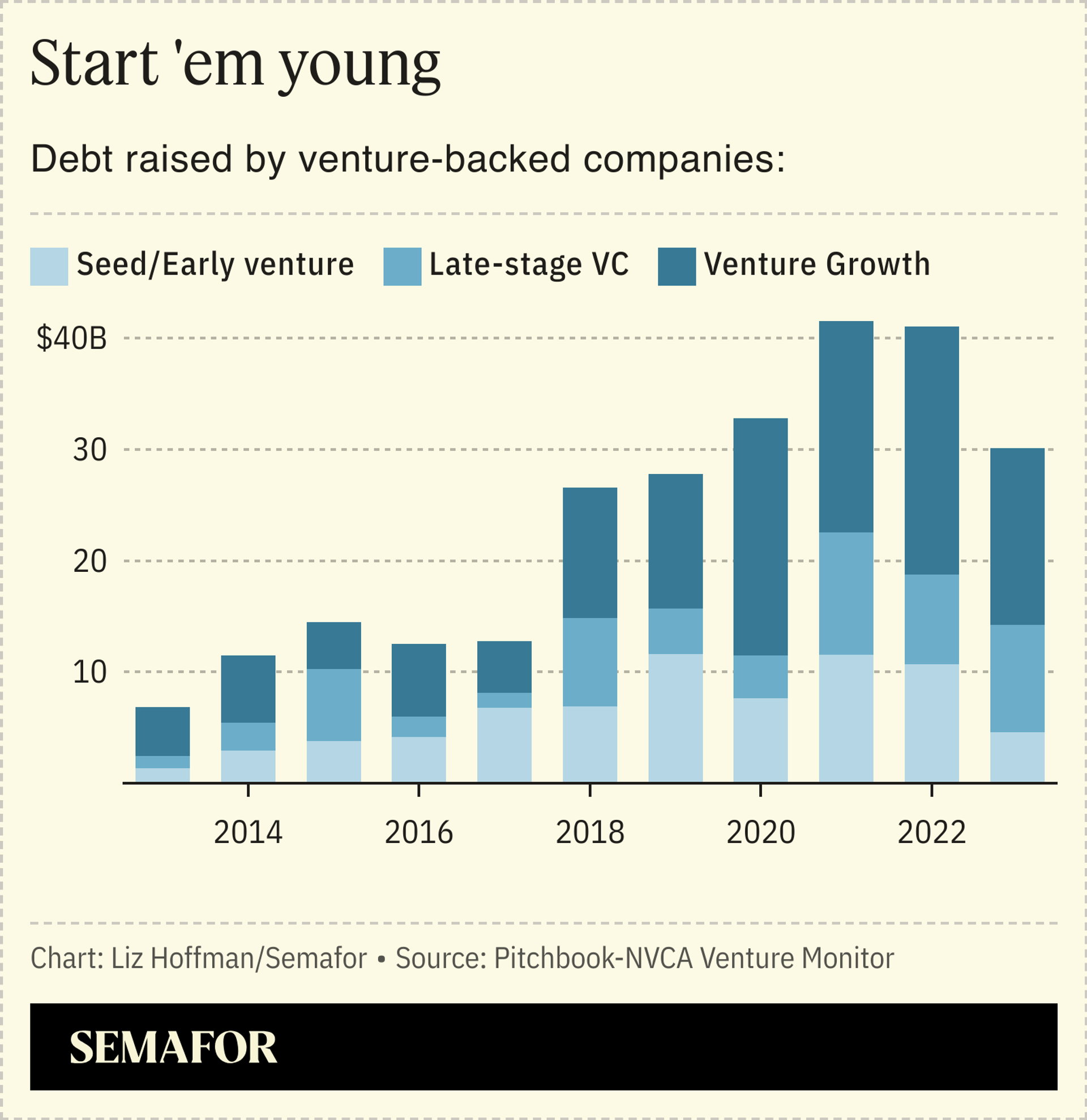

Money-losing tech companies borrowed billions of dollars against the promise of runaway growth from lenders with looser standards. The bill is now coming due.

Loans based on revenue, rather than on profits, were the voguish financial products of 2021 and 2022, on top of the hand-over-first venture capital unleashed by the pandemic. Private credit funds eager to put their money piles to work replaced a bedrock of lending — cash flow is king — with a Silicon Valley embrace of quick growth, sticky subscriptions, and roaring stock markets.

These loans based on “annualized recurring revenue,” or ARR, generally carried tripwires that required borrowers to turn a profit within two or three years or risk a default that could tip them into bankruptcy. Lenders assumed companies would keep growing and that debt would stay cheap and plentiful. Worst-case scenario, an IPO market that seemed to take all comers would bring in fresh cash to repay them.

None of those things happened.

Rising interest rates have made these loans more expensive, at the same time that tech-company growth has stalled out. IPO markets that shut in 2022 haven’t reopened, leaving companies relying on private money that’s stuck in its own pencils-down funk.

“There’s no easy answer” except for companies to cut costs quickly, Holden Spaht, an executive at Thoma Bravo, one of ARR loans’ most enthusiastic users, wrote last year on LinkedIn.

With the clocks on those loans now expiring, lenders are adding more time for companies to repay, rather than sully a track record that’s been pretty clean so far. Private-equity owners are quietly putting in new cash to shore up money-losing companies.

“In 2021, everyone was a ‘have,‘” said Elizabeth Tabas Carson, a partner at Sidley Austin. “Now lenders have a lot of ‘have-nots.’”

Step Back

More than $1 trillion has gone into private credit funds since 2019, according to the IMF. With so much money chasing borrowers, terms got looser. Firms started out offering to lend companies $2 for every dollar of recurring revenue — usually software subscriptions — but by 2022, that was closer to $4, said Ben Rubin, a partner at Proskauer who specializes in private credit deals.

Some lenders waived their triggers entirely, creating a handful of “ARR for life” loans, whose borrowers never have to be profitable. In a recent S&P survey of companies with recurring-revenue loans, the average had $7 million in pre-tax, pre-interest earnings and $191 million in debt.

JPMorgan President Daniel Pinto recently sounded an alarm on private credit, warning that a flood of money would lead to sloppy dealmaking. “Credit conditions will deteriorate, governance will deteriorate, margins will compress,” he said at Semafor’s World Economy Summit in Washington earlier this month. “As [private lenders] become bigger, most likely they will become riskier.”

Know More

Like many standards of financial prudence, the idea that only mature and profitable companies could handle debt started to go out of fashion in the 2010s. Startups like Uber, which were operating at a loss, needed more cash to push into new markets. And because they had been private for so long, they had largely exhausted equity investors in Silicon Valley, who didn’t want their stakes to be diluted even further.

Borrowing solved both problems. Uber and Airbnb each borrowed more than $1 billion from investors in 2016, before private credit was a household term.

It was a profitable strategy for lenders too: A 2018 study found the 10-year returns for venture debt were slightly better than those of venture equity, turning the risk vs. reward calculus in Silicon Valley on its head.

Traditional underwriting standards held on as long as they could, and as recently as 2021, a credit analyst at S&P could call ARR lending a “platypus… so rarely seen that most people know little about it.” At the end of 2019, Thoma Bravo turned heads with the largest ever such loan, $825 million to finance the buyout of an online learning-software company.

Two years later, Thoma Bravo took out a $2.9 billion ARR loan provided by Blackstone, Ares, and Blue Owl, among others, to finance its takeover of Anaplan. Later that year, its chief rival for tech buyouts, Vista, used a $2.5 billion ARR loan to buy Avalara. Neither company had ever turned an annual profit.

What started as a small club of lenders willing to lend to unprofitable companies grew quickly, and by the early 2020s, two dozen firms were in the business. Rubin estimates ARR loans are about 5% of private-credit financing deals Proskauer does.

“It used to be if the five players said no, that deal didn’t happen,” he said. “But if the next five say yes, suddenly it does. That’s not to say it’s a bad asset, but there’s probably more risk in the system.”

Liz’s view

The rise of ARR loans are entirely a function of the private, nonbank lenders and the ocean of money they’ve raised. No bank would lend an unprofitable company four times its annual revenue, at least not for long. (One extremely predictable exception: Silicon Valley Bank had a pretty good business doing these loans.)

An executive at Thoma Bravo admitted as much last year: “If we want to do deals that are ARR loans,” Erwin Mock told Nikkei, “we have to do it in the private debt market.”

That’s not necessarily a problem, and there are plenty of reasons why a loan that makes sense inside a private credit fund, whose money is locked up for eight years, doesn’t make sense inside a bank that funds itself with deposits that might vanish tomorrow.

But the big question hanging over that $1 trillion that’s come into private lenders in the past five years is how it will fare in a downturn. “We haven’t tested it yet,” Goldman Sachs President John Waldron told me recently. “We don’t really have visibility into it, we don’t really understand the quality of it.”

Executives at Blue Owl or Apollo or Ares point to their conservative leverage and comfy perch at the top of the capital stack, with millions of dollars of loss-taking stockholders and junior creditors below them. That’s all true and makes even seasoned bears pretty sanguine about the rise of private credit.

But underwriting models are only as good as the assumptions that go into them, and the assumptions behind ARR loans have turned out to be flawed. What’s more, those flaws have become obvious without a major economic cycle. All it took was corporate buyers of expense-management and hiring software to pull back a bit and IPO investors to sit on their hands for a year.

“If we have a credit cycle, which I think at some point we will,” Waldron said, “we will uncover probably some things we don’t like.”

Room for Disagreement

“Wall Street’s doom-mongers spent years warning that private lenders would be the next bubble to burst when central banks tightened policy,” WSJ’s Jon Sindreu writes. Instead, two years into rising interest rates, these loans have held up better than bank debt.

Notable

- The IMF finds companies that tap private credit markets, instead of bank loans or bonds, are smaller, weaker, and more vulnerable to rising interest rates and economic downturns.

- JPMorgan’s analysts this week on shifts in the credit market: the moving business (banks) vs. the storage business (private funds).