The News

California lender Pacific Western’s shares are tanking, just days after regulators hoped to end the turmoil by selling rival First Republic to JPMorgan.

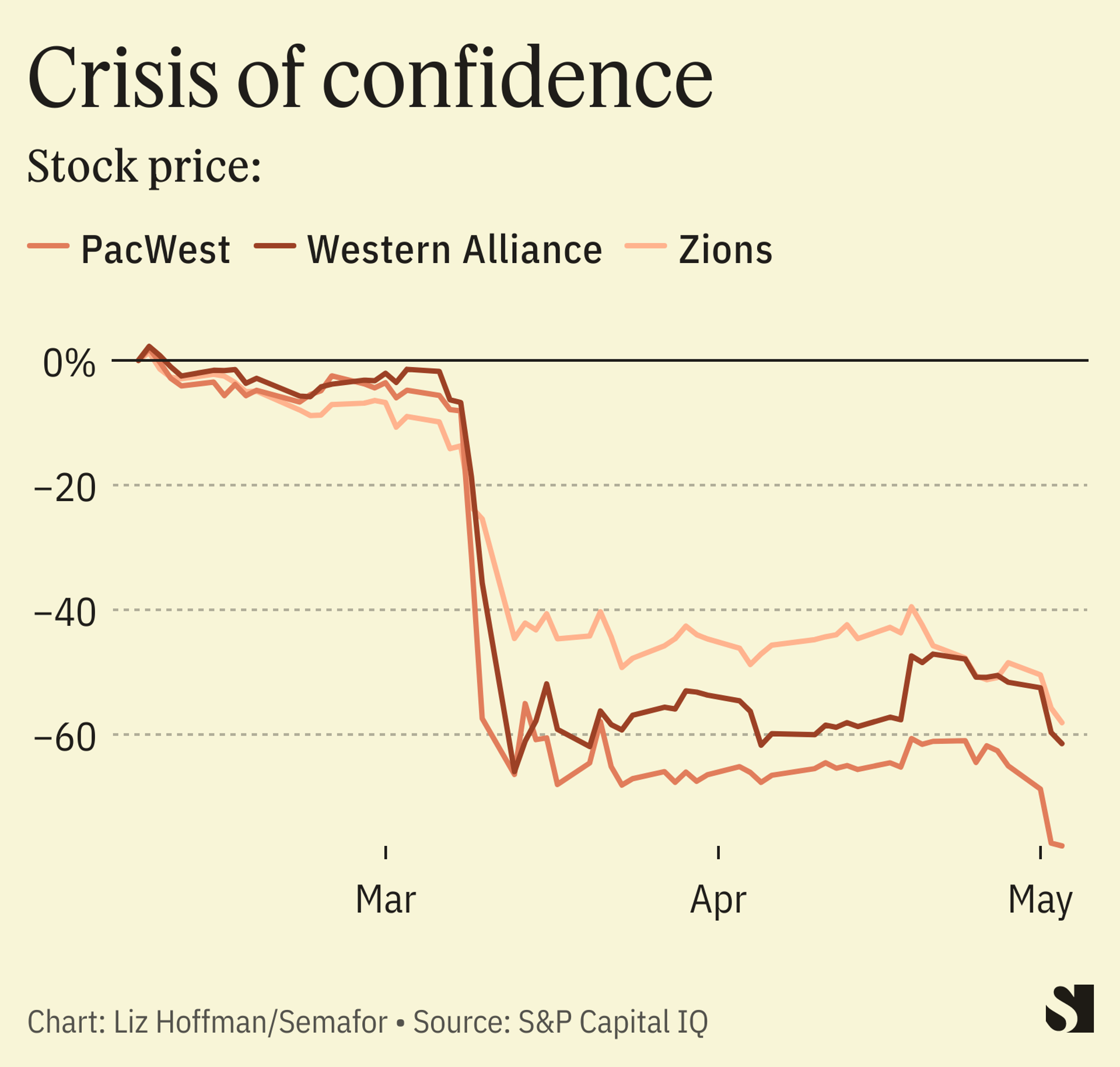

PacWest’s stock fell 60% this morning, following a pattern that has emerged since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March as investors move from one ailing firm to the next. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. arranged a sale of First Republic after its shares plummeted on poor earnings that showed customers had pulled about $100 billion from the bank over a few weeks.

Lenders have shored up their deposits, but investors don’t care. PacWest and Western Alliance, another bank under pressure, both said in recent days that about three-quarters of their deposits are now backed by FDIC insurance.

Liz’s view

In September 2008, U.S. and U.K. regulators temporarily banned investors from selling short financial stocks. “Unbridled short selling is contributing to the recent, sudden price declines,” then-SEC Chairman Chris Cox said, noting that banks (at the time, investment banks were the problem) are uniquely vulnerable to “panic selling because they depend on the confidence of their trading counterparties in the conduct of their core business.”

Swap depositors for counterparties and you’ve pretty well got the current problem. And investors seem to be getting ahead of customers in their rush for the exits. PacWest and Western Alliance actually added deposits in April, after the collapse of SVB and Signature. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said yesterday that the deposit outflows at regional banks had stabilized.

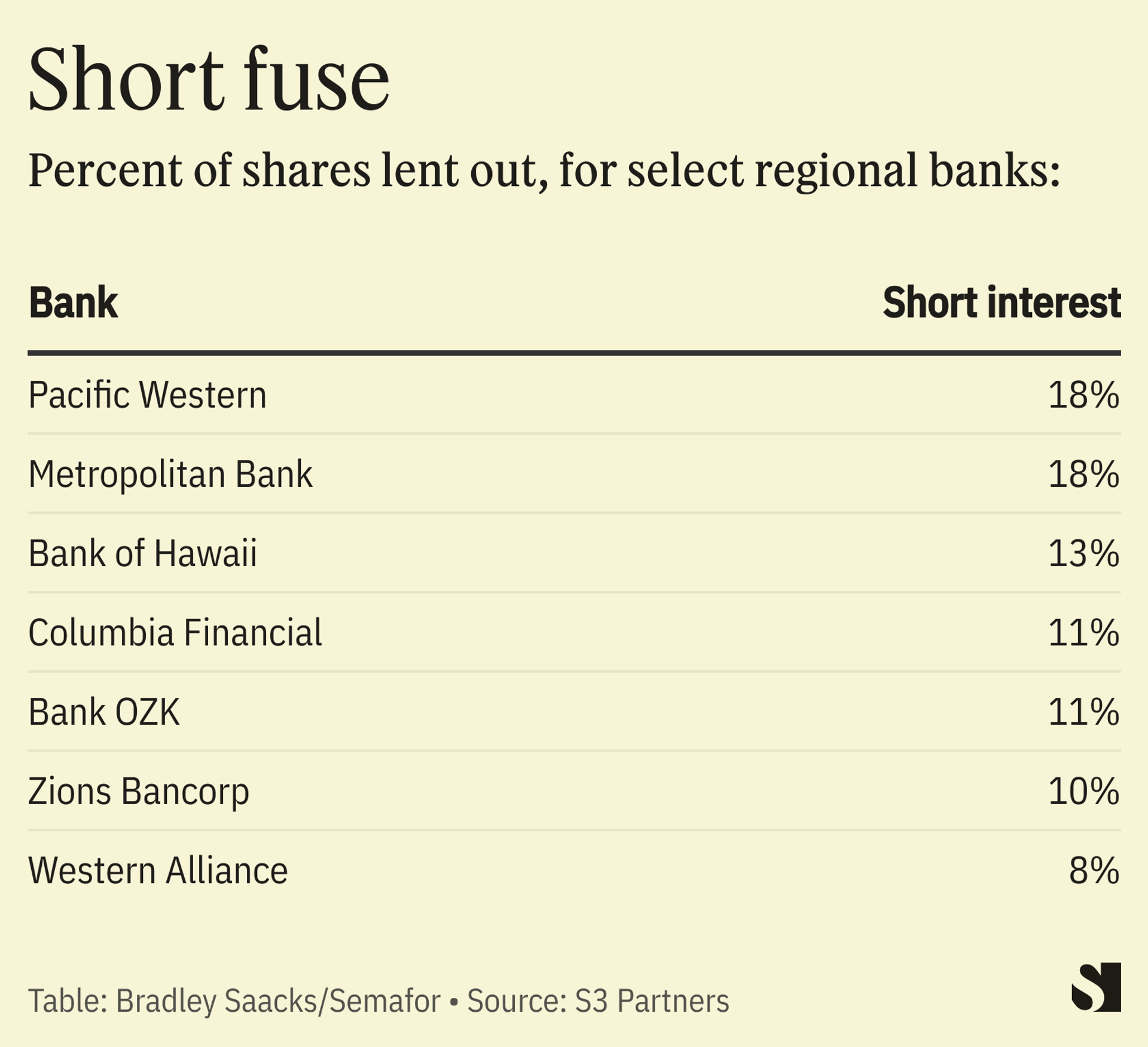

Depositors are no longer panicking, but investors are. It might be time to consider another temporary ban. Never mind that short-sellers don’t actually make stocks go down, and in rational, well-functioning markets, they play a crucial role. But this is no longer a well-functioning market. Short-sellers have made $7.4 billion by betting against the regional banks since the beginning of March, according to data provider S3.

Consider another heavy-handed intervention used in times of stress: the stock market circuit-breakers. If prices plummet, trading is halted for 15 minutes to give everyone time to think about what they’re doing. While the historical evidence is mixed, they seem to have worked in March 2020, during the early panicky days of the pandemic.

Room for Disagreement

“You ban short selling when you think the market is missing something. The market isn’t missing anything here,” former SEC Chair Jay Clayton told me. Any ban would “have to be part of a comprehensive plan,” that involves getting more capital into ailing banks, and lifting or suspending the $250,000 cap on insured deposits, he said. “It’s at best a temporary bridge, and what are we bridging to?”

The View From Europe

The collapse of Credit Suisse, which was hastily merged with Swiss rival UBS, was partly blamed on the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. But the pain hasn’t seemed to have spread to other European lenders. Italy’s UniCredit on Tuesday raised its financial targets for the year. Germany’s Deutsche Bank reported solid first-quarter results and its stock is up 10% since late March.

Notable

- The 2008 short-selling ban may have bought troubled banks some time, but it increased trading costs by an estimated $500 million, according to a 2012 paper from the New York Fed.