The News

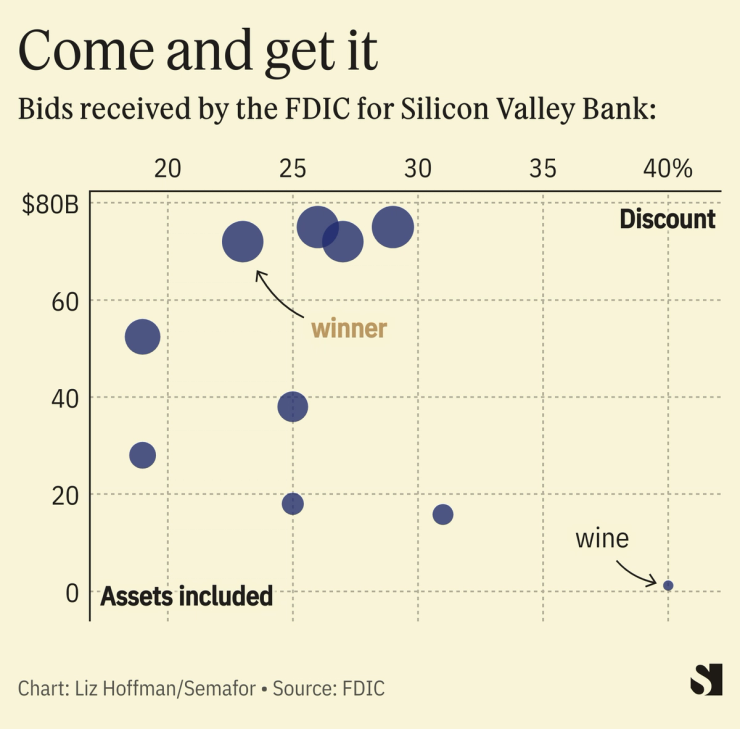

Ten firms bid for Silicon Valley Bank after it was seized by regulators in March, while another 10 wanted pieces of it, suggesting an auction that was more robust than previously known.

First Citizens, the North Carolina bank that won, offered the government the best price on the biggest chunk of assets, according to data quietly released last night by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. It bought $72 billion of loans at a 23% haircut, and took all of SVB’s deposits.

Three other firms offered less money for roughly the same pot of assets, and a handful of others bid for smaller chunks, including one steeply discounted proposal for SVB’s $1 billion in wine-related loans.

The pitches are a window into how financial players, including private-equity firms (Blackstone, Apollo, and Sixth Street all submitted bids for parts of SVB) and fintech firms (so did Brex, which provides corporate credit cards), are sizing up potential bargains in the turmoil.

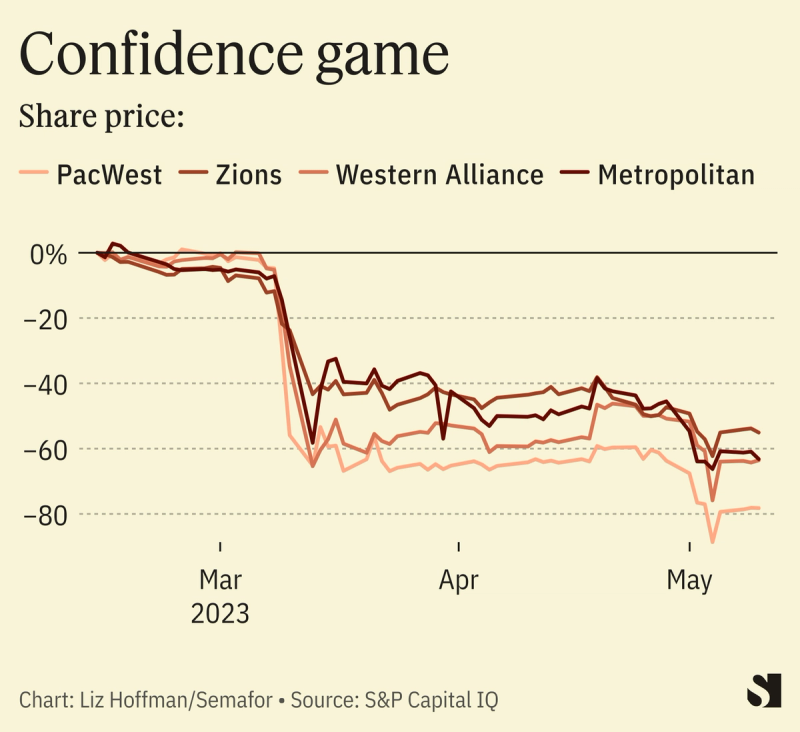

The sale of First Republic to JPMorgan failed to end the pain, with Pacific Western’s stock down 25% Thursday morning after it said its deposits, which had stabilized, dropped sharply last week.

Liz’s view

I’ve criticized the FDIC’s handling of the regional-banking crisis as too slow, messy and politically tinged. The government initially shut the biggest U.S. banks out from bidding for SVB, Semafor has reported, and the two weeks it took to ink a deal only contributed to the widening panic that has since taken down First Republic and is now threatening others.

The new release shows an auction that was more robust than I and, I think, other reporters, sensed back in March. And in the balance between getting the best price for the most stuff — anything left behind would have to be managed for years by the FDIC itself, or farmed out to an asset manager for a fee — the government appears to have struck a pretty good deal.

If there are more failures ahead, I think nontraditional bidders’ odds get better. Failed banks have two kinds of value to acquirers: financial value (buying deposits and loans at a discount is a good trade) and franchise value (buying bankers and their clients at a discount is also a good trade).

But the latter only matters for other banks. Apollo isn’t in the business of making small-business loans or offering concierge wealth-management services. It is in the business of buying big distressed portfolios.

And the two regional banks with perhaps the most franchise value are already gone; SVB and First Republic had real clients, strong brands, and talented bankers. The further you go down the ladder of increasingly anonymous regional banks, the less franchise value you’ll find. That gives purely financial bidders, like investment firms, a leg up over other banks, and presents a political problem for regulators wary about the optics.

Room for Disagreement

Republicans in Congress have been critical of how regulators handled the SVB sale, including the time it took to reach a deal. As head of the House Financial Services Committee, Patrick McHenry has already held several hearings focusing on the FDIC’s response, saying “We need competent financial supervisors. But Congress can’t legislate competence.”

The View From the top

The biggest U.S. banks will pay $15 billion to cover what it cost the FDIC to resolve SVB and Signature bank, under a new proposal from the agency. That money goes into the FDIC’s deposit insurance fund, which had $128 billion in it as of year end but has now been tapped three times to protect uninsured depositors.

Their disproportionate bills reflect the fact that the biggest firms “benefited most” from the rescues, FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg said this morning. It’s unclear exactly what he means — money poured into big banks from panicked customers of regional firms — and Jamie Dimon begs to differ: “The notion that this meltdown was good for them [us] in any way is absurd,” he wrote in his annual letter last month.

Notable

- Dig into the SVB bids yourself.