The Facts

Three years after the U.S. government rescued the country’s airlines, the bill is this: $62 billion spent, $19 billion repaid or expected to be, a few billion in savings elsewhere, and $1.4 billion in airline stock that remains underwater, according to a Semafor analysis of federal data.

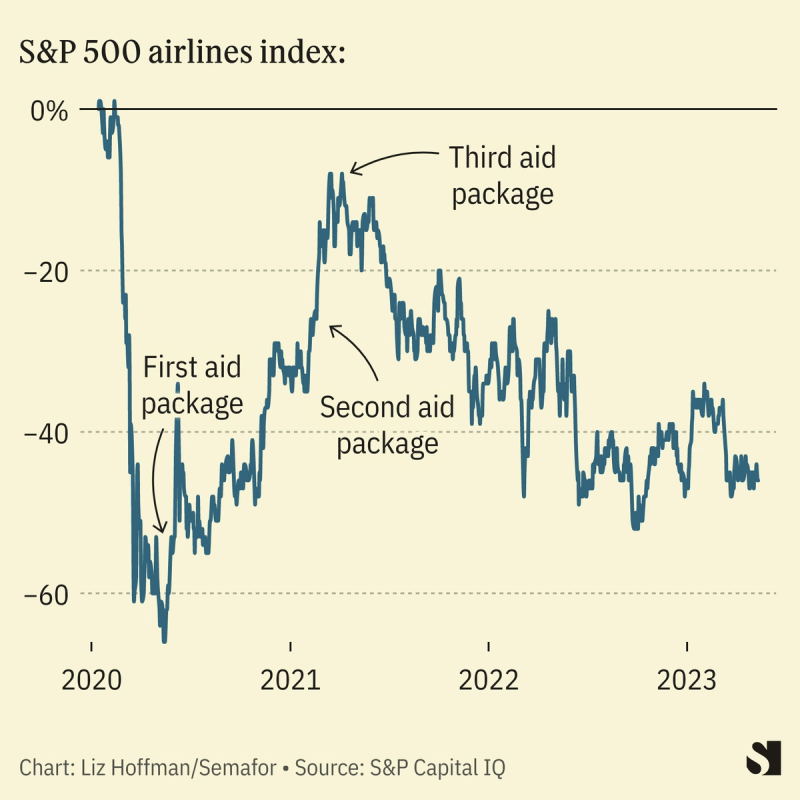

In the spring of 2020, nobody was flying and Washington approved the first leg of unprecedented aid for U.S. airlines and contractors. Congress re-upped it in December 2020 and again in the spring of 2021.

People are traveling again, though not quite at pre-pandemic levels, and airlines are grappling with worker shortages, labor unrest, and higher fuel prices. Delta and United both posted losses in the first quarter and American eked out a small profit, but all are projecting a busy summer.

The government’s takings might increase a bit if airline stocks recover, but this rescue looks quite different from the 2008 bailout of Wall Street, which ended up making billions for taxpayers. This one will not.

Liz’s view

I’ve spent the past few weeks talking with people who helped design and pass the airline aid, and as you’d expect, each of them defended it, with some caveats that I agree with.

“It’s as simple as all of the airlines would have folded,” Mitchell Silk, a former Treasury official who worked on the program, told me last week.

The first rescue package, in April 2020, was clearly necessary. Airlines were burning hundreds of millions of dollars every day. Even Delta, the strongest of the big carriers, had about two months of cash, I reported in my book, which looks at the pandemic’s economic toll.

The second round, in December 2020, is debatable. The economy was starting to open back up by then, as were the fundraising markets. On the other hand, omicron was sweeping through the country.

The third package, a $15 billion slug passed as part of the American Rescue Plan early in the Biden administration, was clearly a mistake. (“That wasn’t us,” Silk said briskly when I asked him about it.) By then people were flying again, and in my book reporting at the time, I found no airline executive who was considering firing anyone then.

I’m loath to call the airline aid a bailout, which suggests letting someone out of a problem they created. Airlines definitely prioritized shareholders in the 2010s, but no company is set up to survive revenue going to zero. And unlike 2008, this time around, the recipients didn’t cause the crisis we were saving them from.

Another thing each person I talked to told me was that the program was never designed to make money. That’s unfortunate.

Bailouts are sometimes necessary, especially for airlines and banks, which are now back in the bailout discourse. Both are essentially national resources in private hands, and we’ll continue to save them from problems of their own making (banks, every decade or so) or outside shocks (airlines, every two decades or so).

And bailouts that make money ensure that the next time one is needed, there will be more political will to enact it.

Room for Disagreement

Last year’s massive flight cancellations “are a good reminder of what a raw deal those bailouts were for taxpayers and consumers,” wrote Christian Britschgi in the libertarian Reason magazine. “Rather than allow the shock of the pandemic to create some needed disruption in the passenger airline industry, Congress chose to prop up a messy status quo.”

Know More

The program had several pieces:

- $59 billion, which won’t be repaid, to cover payroll for hundreds of thousands of workers. Most went to flight attendants, gate agents and others at passenger airlines. About $4.5 billion went to employees of cargo airlines, which ended up as pandemic winners and needed little help, and defense contractors.

- $17 billion in loans linked to that payroll aid. Debt was cheap then, and over that term, Treasury can expect to recoup between $400 million and $900 million in interest, plus the principal, according to Semafor’s analysis. (The loan charges 1% for five years, and escalates after that.)

- Separately, Treasury lent $2.6 billion secured by airlines’ frequent-flier programs, gates, spare parts and whatever else of demonstrable worth they had lying around. Those loans were expensive, and stronger airlines like Delta and Southwest never touched them. American and United borrowed as little as they could and paid it back quickly.

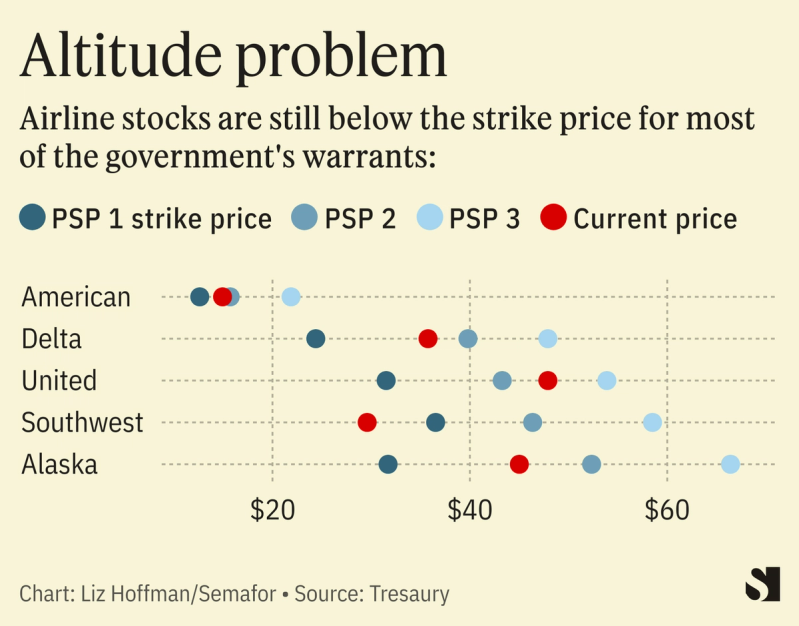

About $1 billion in loans are outstanding to small airlines, travel agents, and contractors. They’ve paid $107 million in interest as of April and will owe another $190 million, according to Semafor’s analysis. - Treasury received stock warrants in the largest airlines to let taxpayers share in the recovery. The instruments are worth $1.4 billion at their strike price, according to our analysis.

But airline stocks are lower than they were in all but the earliest days of the pandemic, which means the government’s sweeteners, struck at the stock price when the aid was agreed, is worthless for now.

- There are squishier inputs, too. Paying airline workers directly kept them off unemployment rolls, which would have added costs. I asked Treasury to quantify that and a spokeswoman said “billions” were saved. Billions more came in income taxes.

And while nobody who didn’t have to fly during the spring and summer of 2020 was flying — I got back in the air in June of 2021 to go visit, fittingly enough, an airline CEO — front-line workers and government employees were still traveling. A Transportation Department analysis estimated it would have cost the government $3 billion to charter enough flights, according to a person familiar with the matter.

The View From Europe

European governments were heavier-handed in their aid, taking direct stakes in the likes of AirFrance-KLM and Lufthansa. The bailouts there have been politically unpopular and unprofitable for Paris and Berlin, and attracted scrutiny from competitors, notably RyanAir, whose CEO said he couldn’t compete with “these state-aid, crack cocaine junkies.”

Notable

- “It is fair to say that we socialized the airline industry’s losses and largely privatized the gains,” Andrew Ross Sorkin wrote in the New York Times in 2021 in one of the the first forensic looks at what the U.S. got for its money.