The News

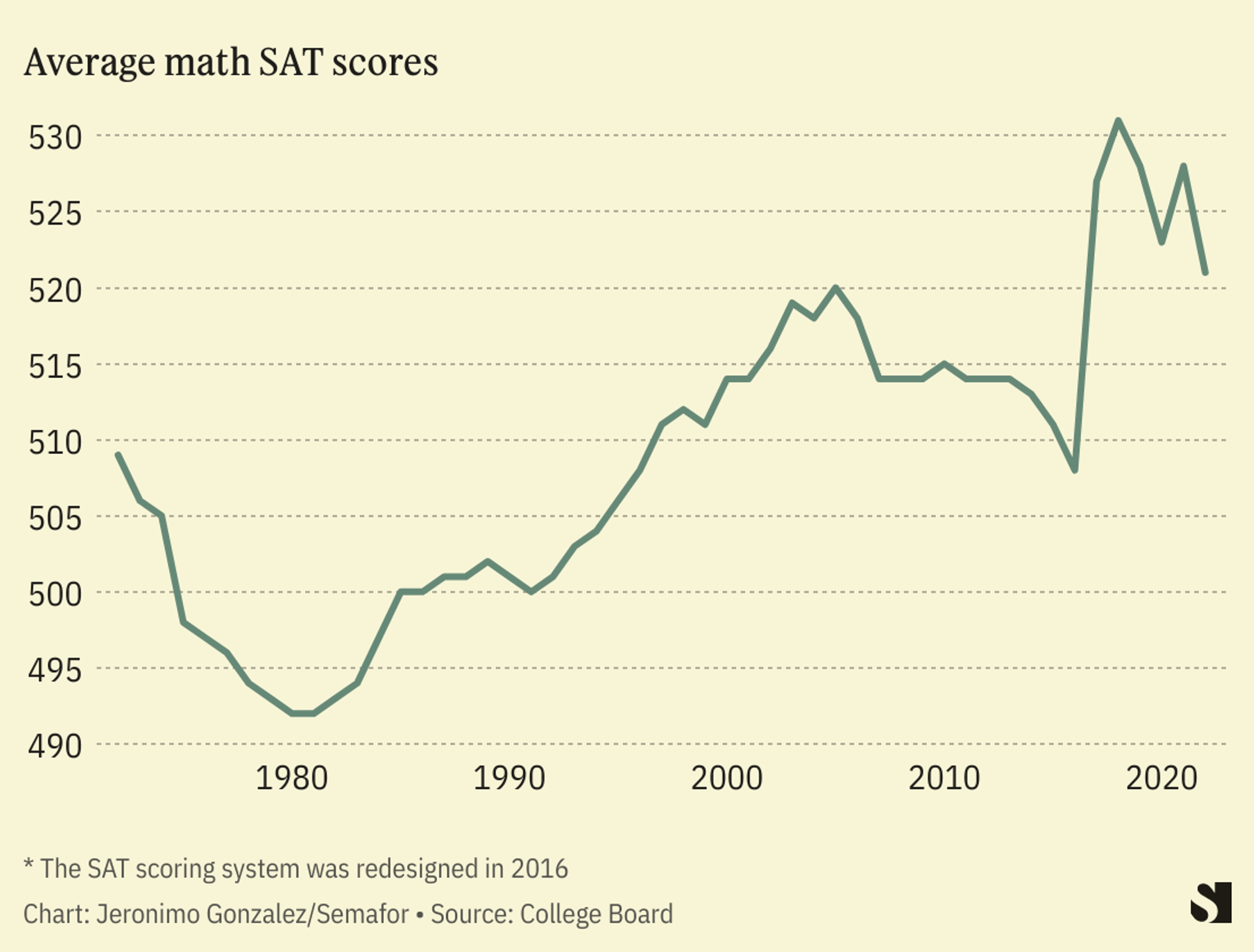

Jamaal Bowman, a former middle-school principal who is now in the U.S. Congress, complained recently that annual standardized testing “disproportionately harms Black and brown students and students with disabilities.” He introduced a bill eliminating federal mandates for testing in math, reading and language, dating from the 2002 No Child Left Behind Act.

His side has recently been winning this long American argument. In the wake of the racial justice protests of 2020, and in an effort to dodge legal challenges to affirmative action, many U.S. colleges have dropped SATs as entry requirements, adding heat to a furious and long-running debate on the subject

In this article:

Tom’s view

Bowman is not wrong, exactly. Richer students do tend to perform better than poor ones on standardized tests, and in the U.S., White and Asian students have on average performed better than Black students.

The problem is that every other available form of grading is more biased, two educational policy researchers, Sam Freedman and Daisy Christodoulou, told me. You might think that teacher assessment would be fairer: Teachers are not just looking at how students perform in high-pressure exams, the thinking goes, but their whole educational performance. But teachers’ assessments are consistently biased against poor and ethnic minority children.

Assessing by grade-point average in the U.S. system is also racially stratified. Assessment by essay is more biased against poor students than are SATs, according to a 2021 study. Evidence from “gifted and talented” programs found that universal standardized screening picked up more disadvantaged and minority students than traditional parent-and-teacher-led referral systems. Meanwhile, SAT performance correlates well with college attainment: It doesn’t, as some suggest, merely reflect income levels or how good you are at SATs.

Standardized tests don’t introduce inequality: They reveal it. The deeper problem is that disadvantaged and minority students are systematically less prepared for college life. Ending standardized testing is like seeing that a room is messy and turning off the lights rather than cleaning it up.

The View From The U.K.

During the pandemic, children in the U.K. were unable to take exams, and entry to universities was instead determined with an algorithm, taking into account the students’ performance to that point and the school’s previous overall results to help put the individual student in context. Many students found their grades were lower than their teachers had predicted, leading to an outcry, so the algorithm was abandoned and replaced by teacher-assessed grades.

A 2021 study found that, far from reducing inequality, the move to teacher assessment disproportionately benefited children whose parents were university graduates, perhaps through unconscious bias, or perhaps because they were more likely to “lobby their child’s school to ensure they receive favourable assessments.”

Notable

- Some students from wealthy families are gaming “holistic” college entrance assessments by paying to get research published in peer-reviewed journals, to make them look like more rounded applicants, ProPublica reported.