The Scoop

Blackstone has over-succeeded in the private-equity industry’s race to raise money from everyday investors.

The firm has raked in $150 million a week for a buyouts fund aimed at retail investors that launched in January, a haul that has spurred copycat funds from rivals coming late to the game.

The fund, known as BXPE, was the one of the first to take private equity to the masses and at $4 billion is by far the largest. But in a quiet market for deals, Blackstone now has more cash than places to put it and is quietly striking deals with smaller private-equity firms to piggyback on their buyouts, people familiar with the matter said.

The firm has been negotiating with middle-market firms including Kohlberg & Co. to put some of its money into their deals. About 15% of BXPE’s money is now in non-Blackstone transactions, one of the people said. Both firms declined to comment.

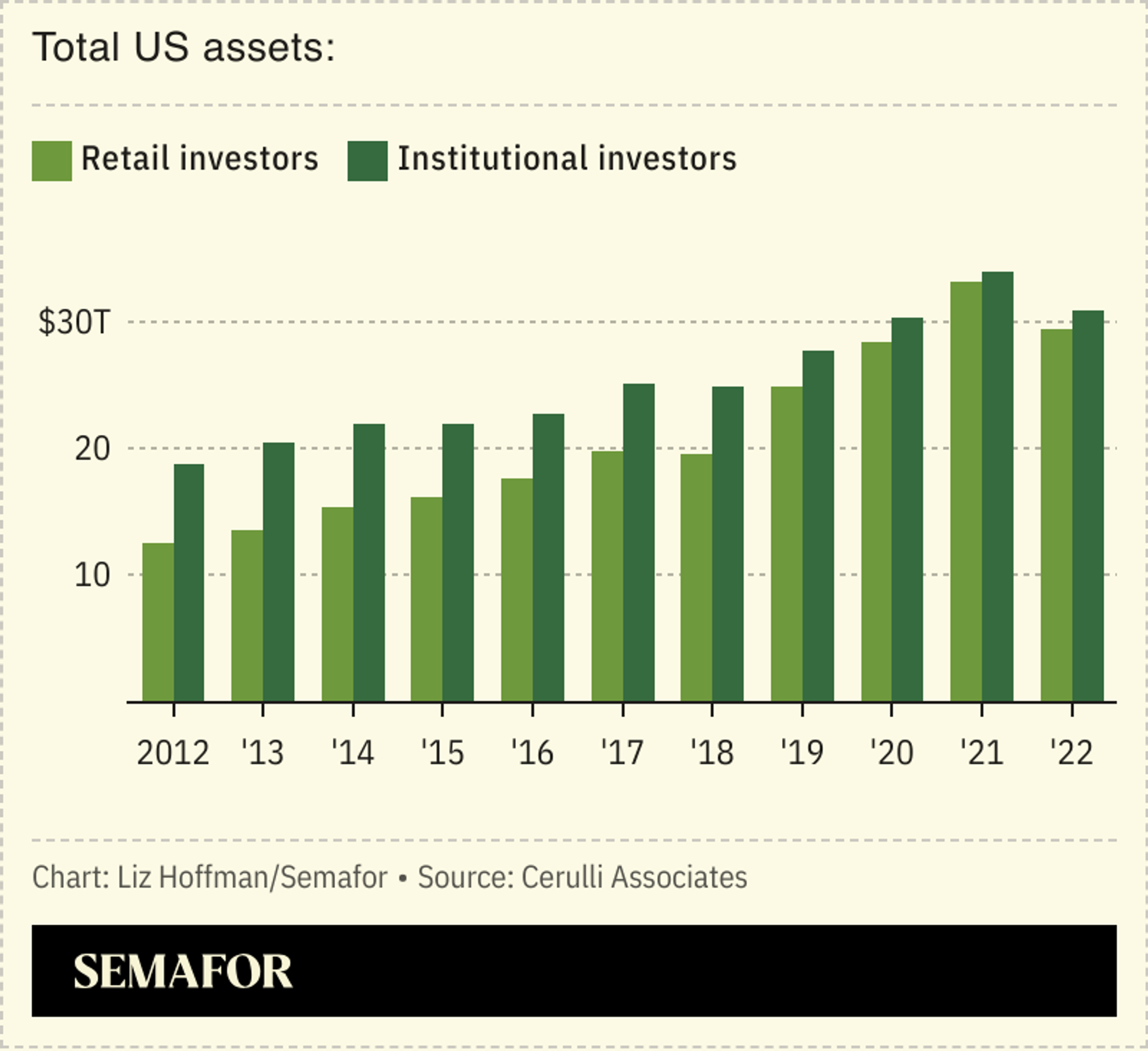

Private-equity firms have historically raised money from pension funds, insurers, and endowments — big players that can write big checks. But for the first time, individual investors have almost as much to invest as those institutions, according to Cerulli, which pegs US retail assets at $30 trillion. Private fund managers are scrambling to get their share.

KKR raised $1.8 billion over the past year from 12,000 individual investors for an infrastructure fund, and is partnering with money managers to sweep more mom-and-pop money into its buyouts funnel. Carlyle’s first co-investment fund aimed at retail investors went live on Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch’s client portals last week, and CEO Harvey Schwartz, who spent a few days last month wooing wealth managers on the West Coast, has said a private-equity flavor is coming in 2025.

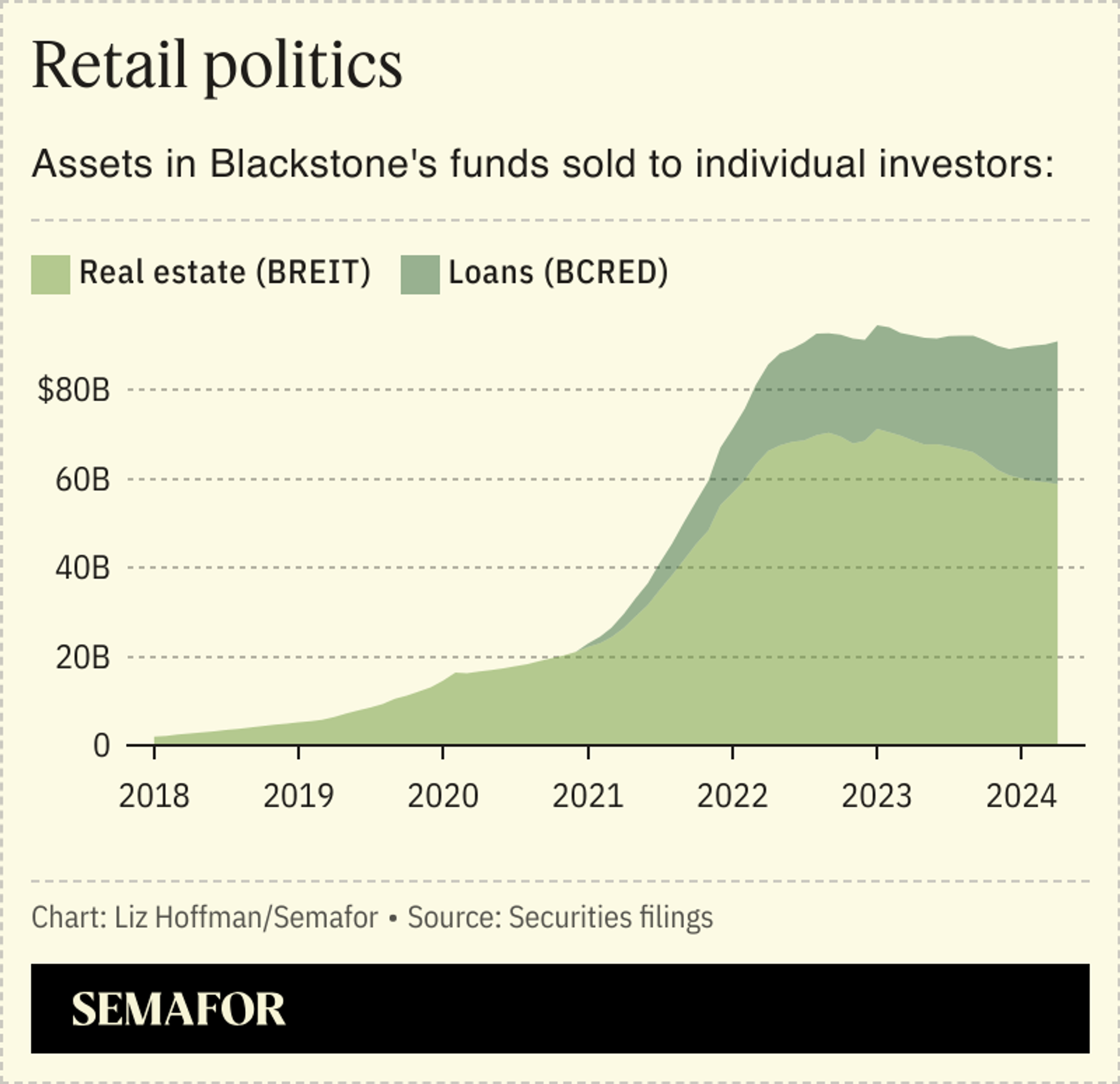

Blackstone has a head start. Its first fund aimed squarely at retail investors, a real-estate fund called BREIT, launched in 2017. A similar loan fund, BCRED, followed in 2021. Both have raised money at an impressive clip and report annualized returns above 10%.

But BREIT has been hit by waves of redemptions as investors, unnerved by a downturn in commercial real estate, ask for their money back. At times, withdrawals have exceeded monthly limits set by Blackstone, forcing the firm to sell assets to raise cash. Things have calmed down recently, and the cracks haven’t deterred investors in BXPE, who are piling in at a rate of $25 million a day.

BXPE isn’t as narrow as real-estate or credit, and can invest across a few Blackstone playbooks, including straight buyouts, secondaries, and life sciences — designed, Blackstone President Jon Gray said recently, to be “as broad as possible, so that we could scale the product and we could be flexible on behalf of investors in terms of where we deployed it.”

Liz’s view

This is a high-class problem to have. But it’s a problem, and Blackstone looks right now like the dog that caught the car.

For one thing, too much money chasing too few deals almost never ends well. And a suburban dentist — forever the prototype of a semi-rich everyman drawn to the glitz of private-equity — isn’t giving Blackstone money thinking it’s going to end up in the hands of a middle-market buyout shop.

Blackstone could simply slow down its fundraising. It’s not a bank, and doesn’t have to take every dollar people want to give it. Investment firms cap the size of funds they raise from big institutions all the time, knowing there’s a limit to how profitably they can put that money to work.

But Wall Street isn’t in the business of turning money away, especially not now, and especially not publicly listed firms, which have become asset-gathering machines whose stocks trade on how much money they invest, rather than how well they invest it.

Blackstone last summer became the first member of the club to hit $1 trillion in managed assets and has set another target that would see it nearly double in size again over the next 10 years. A lot of that growth is expected to come from retail. Already one-quarter of the firm’s assets today are from individual investors.

Shelf space for private-equity funds at Merrill Lynch is as fiercely contested as shelf space in the cereal aisle at Walmart. “Wealth management firms are not going to put thousands of names on their platform. They’re going to put three in a segment, or maybe five,” Gray said at an industry conference last month. “And in almost every case, Blackstone will be one of them.”

Turning off the spigot risks losing ground to rivals and the attention of financial advisers, so firms are loath to do it.

A notable exception: HPS recently slowed its fundraising at private banks because it couldn’t find enough investments that fit its criteria. That shows commendable restraint, especially heading toward an IPO that will value the firm largely on how much money it manages. HPS declined to comment.

“Suitability” is a word you’ll hear a lot around this retail land grab. Conventional wisdom says that riskier investments only work for people who can afford to lose it all; Bloomberg’s Matt Levine calls it “earning the right to get swindled.” But even millionaires can be irrational. And retail investors, no matter how rich, tend to run for the exits in a downturn. The question is whether any amount of investor education and disclosure can turn a big-boy product into a small-fry one without serious problems.

“It’s all about how much illiquidity can you suffer to get that sort of a return,” Goldman Sachs President John Waldron said in April at Semafor’s World Economy Summit. “For the $500,000 or $1 million [net worth] person, that’s obviously harder. That’s the trade-off that constantly needs to be judged.”

Room for Disagreement

“We’re not waiting for the all-clear sign to invest,” Gray said in April. He was talking about a muddying outlook for interest rates and economic growth, but it’s also a core bit of the DNA at Blackstone, which has never minded being early, as long as it’s right. The rise of retail in private markets is inevitable and there is likely a significant first-mover advantage in laying the distribution pipes, cozying up to advisers, and — and this is key — making money for investors, all of which Blackstone has done ahead of rivals.

The View From Jay Clayton

When he ran the SEC under President Donald Trump, Clayton tried to change those rules to let more plebeians behind the velvet rope. He succeeded only marginally, but has continued to stress the absurdity of putting retirement assets that won’t be touched for decades into easily traded stocks and bonds instead of more profitable, but less liquid, bets.

“You’re paying for liquidity that you don’t need and can’t access,” he said last year. “Capital formation these days largely comes from outside the public markets, yet the investing public is largely held outside those private markets.”

Correction

An earlier version of this story said that BXPE was the first private-equity fund marketed to retail investors. KKR’s version, known as KPEC, launched last summer.