The News

Honduras announced new measures to tackle organized crime, including the building of a megaprison that could host up to 20,000 inmates, doubling the country’s current prison capacity.

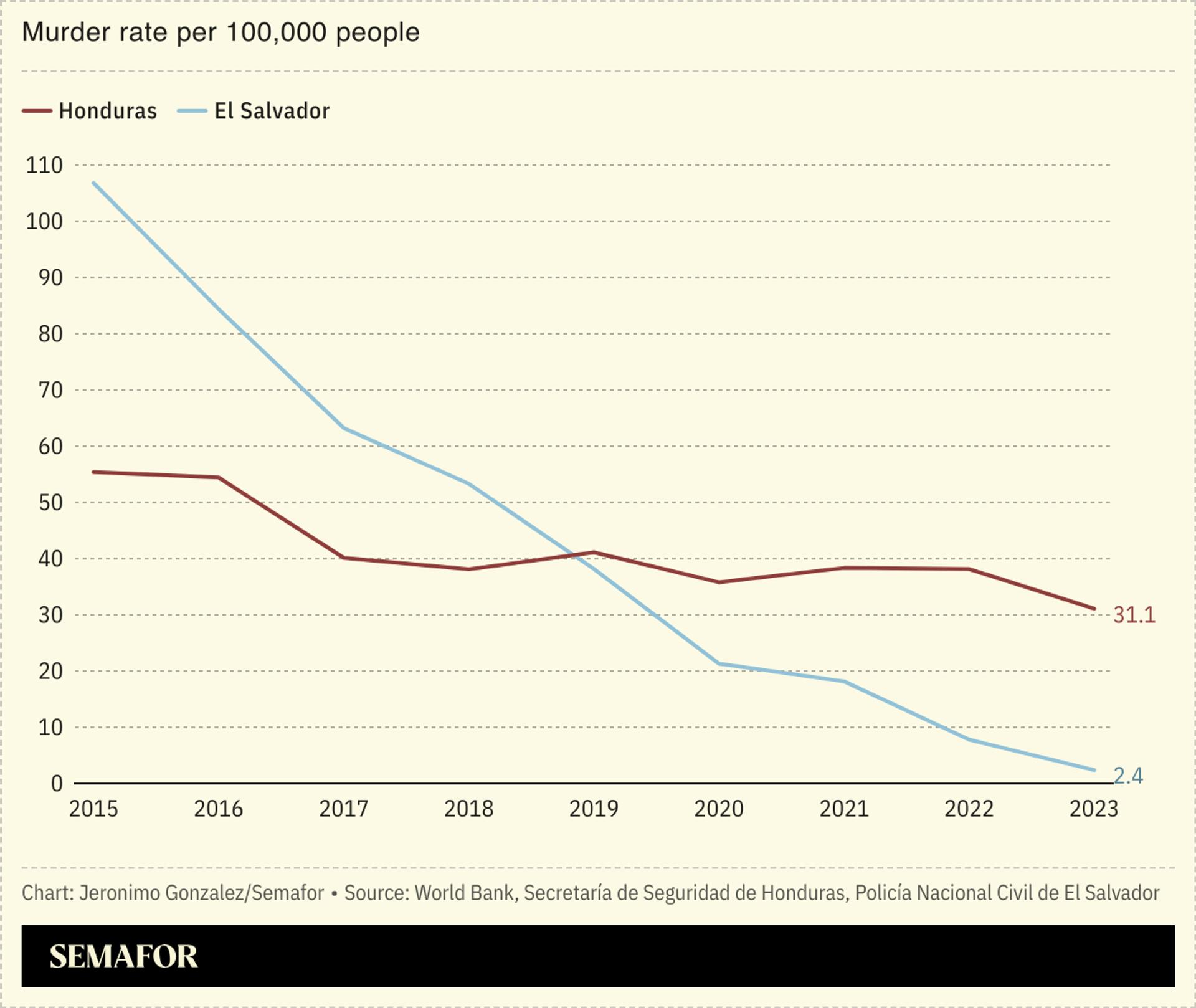

The plan also includes holding mass trials and labeling gang members as terrorists. Honduras President Xiomara Castro placed the country in a state of emergency in December 2022, giving the government more power and suspending parts of the Constitution, in an effort to curb the gangs’ dominance over parts of the country, which has one of the highest murder rates in the world.

SIGNALS

Plan echoes El Salvador’s zero-tolerance approach to violent gangs

Honduras’ megaprison plan and broader crackdown on violent crime closely resembles that of neighboring El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele. Bukele’s tough-on-crime strategy has led to a drop in murder numbers and a rise in his approval rates. Other Latin American countries like Ecuador have attempted to follow the “Bukele plan,” and the president of Honduras reportedly met him in early June to discuss his successful measures. But human rights groups say Bukele’s approach has led to widespread human rights abuses, and in Honduras, has proven largely unsuccessful so far, with gangs and drug-trafficking groups still controlling large swathes of the country, El País reported.

Environmentalists oppose controversial ‘Honduran Alcatraz’ plan

The new megaprison project in Honduras follows another 2023 plan for a maximum-security detention center — a “Honduran Alcatraz” to be built on a remote island off the coast of the country to imprison gang leaders. El País characterized it as a “desperate” measure from the government to try and curb violence, and the plan also drew criticism from biologists over its potential environmental impact on the island, an uninhabited and diverse ecosystem that was designated as a protected territory. The government recently claimed they had obtained the required environmental permits to go forward with the island prison.

Inmate violence at megaprisons raises questions about their effectiveness

Other megaprisons across Latin America housing thousands of inmates see violence, riots, and the dominance of gangs, InSight Crime wrote, raising questions about the effectiveness of such detention facilities in combating violence. One Latin America expert predicted last year that this could likely happen in Honduras: “A new prison is quite useless if you don’t first regain control of the others you already have,” he told the Associated Press. “Criminal gangs have shown throughout their history that they can adapt.” A wave of violence in a women’s prison last summer that resulted in the death of 46 inmates prompted El Faro to describe it as another episode in “the tradition of death in Honduran prisons.”