The Scoop

A startup that spun out of Airbnb to manufacture tiny homes at a factory in Mexico is launching a mortgage product it hopes will relieve California’s housing crisis.

Samara, which raised $41 million in 2023, is now getting into the financing business. It will start offering a mortgage that lets homeowners take equity out of their primary house to install backyard units, technically called accessory dwelling units, or ADUs.

The company is providing a financing and logistics shortcut for what is perhaps the central policy challenge facing both political parties: A housing crisis that is concentrated in cities like San Francisco and New York but driving unhappiness around the country.

It’s taking advantage of the momentum of the “Yes in My Backyard” (YIMBY) movement, which last year won a change to California law overruling bans on infill. Along with a good financing deal, it could — if widely adopted — offer a way to increase density in some neighborhoods, whether neighbors and local politicians like it or not.

“This is literally people saying, yes, I want this, in my backyard,” said Samara’s CEO, Mike McNamara, who launched the company alongside Airbnb co-founder Joe Gebbia. “The politics around this debate have shifted.”

It’s not just housing policy at Samara’s back. The company is seizing on two financial trends: Rising prices that have left homeowners sitting on a gold mine of equity in their houses, and Wall Street’s insatiable appetite for newfangled loans.

The average homeowner has $300,000 of equity in their house, up from $182,000 before the pandemic, according to CoreLogic. Samara’s offering mimics a second mortgage, but is cheaper, with rates starting around 6.5%. And because about half of its customers already use their ADUs as a rental, there’s an income stream that investors can underwrite.

Samara declined to name its financing partners. Its CFO, Chris Wasley, said it will work with banks, investment funds, and securitization channels. (Financing mortgages on its own balance sheet would be a strange use of very expensive venture money.)

In this article:

Know More

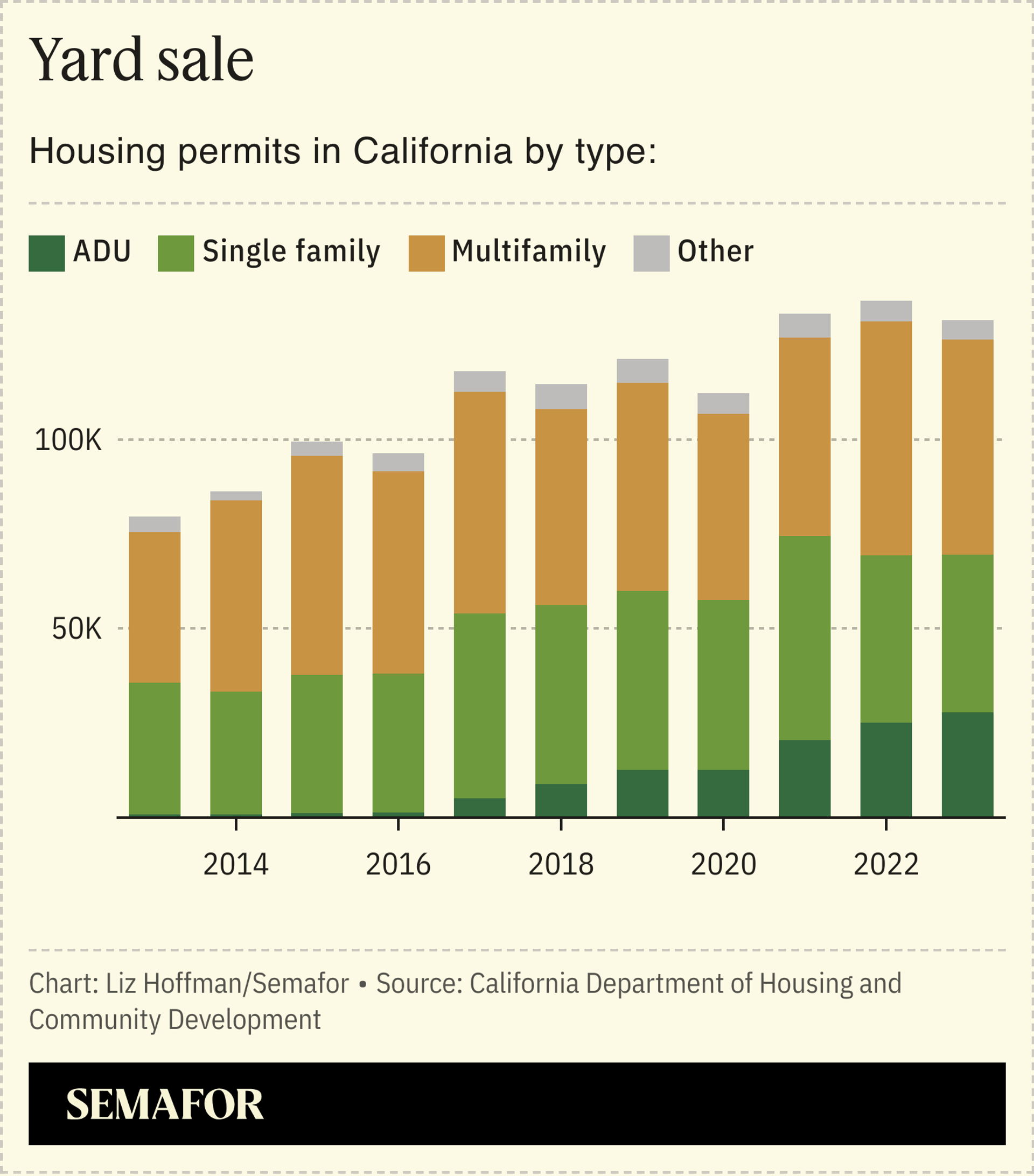

Applications for ADUs in California, one of the nation’s most strapped housing markets and the epicenter of the grimy politics associated with it, have risen 20-fold since 2016. About one-quarter of the 110,000 housing permits the state approved last year were for ADUs. States including Colorado, Maine, New Jersey, and Vermont have all taken up or passed laws that would change zoning laws to make it easier to build backyard dwellings. Last week, San Jose became the first city to let owners turn their ADUs into condos and sell them separately.

Whether backyard dwellings will make a meaningful dent in the housing shortage depends on how people use them. Samara’s aesthetic — airy, with clean lines and cathedral ceilings — seems designed for a particular type of Airbnb traveler. There’s a reason a chunk of its seed money came from Airbnb, which is always trying to attract new listings. And wealthy California families using ADUs to house nannies or private chefs will do little to improve the political climate.

But as the largest generation in US history retires without enough health aides and assisted living facilities to care for them, more parents are moving in with their kids. And the housing crunch means more young adults are living with their parents. Nearly 40% of men between the ages of 25 and 29 were living with an older relative in 2021, according to Pew Research.

Samara sees that trend as key to its fortunes. Customers can use ADUs to “house the grandparents or the kids that come home from school,” McNamara said.

Liz’s view

We wrote last week about the seemingly endless list of things being securitized right now, spliced and diced and sold into a waiting sea of money at investment funds. Recent weeks have seen novel bonds backed by home heat pumps, Subway franchises, IP addresses, and Sotheby’s art loans. It’s all “a bit spicy,” even for Janus Henderson’s head of securitized product.

“Clearly this should be an asset class,” Wasley, Samara’s CFO, told me, using the language of this massive post-2008 shift in how seemingly everything is being paid for these days. Samara’s loans “should trade below second mortgages and slightly above first mortgages” in terms of investor returns, putting it in a sweet spot for Wall Street investors.

The impulse for companies to turn their physical products into financial ones is powerful. Rooftop solar companies figured this out years ago. (Wasley spent six years at Solar City, lining up financing for its customers.) See this chart on auto loans. Online shoppers spend more when they can buy now and pay later, so we now have a thriving BNPL asset class, in which PayPal sells checkout loans to KKR. Lots of rich people like sports, so there is a thriving trade in team stakes.

In theory, plentiful financing should make purchases cheaper, as it did for rooftop solar. But lubricating big purchases — Samara’s two-bed-two-bath model starts at $400,000 — through financial engineering can end badly. It can gull people into taking on debt they don’t understand and can’t repay, as we saw with the government’s green-energy PACE loans.

Homes tend to appreciate in value, unlike solar panels whose technology becomes obsolete, or cars whose value starts declining the minute it’s driven off the lot. Whether the same will be true for tiny homes is less clear to me, but Wall Street firms will be all over this. Some will regret not having thought of it themselves.

Notable

- Two timely conversations about why it’s so hard to build things in America. Ezra Klein on San Francisco’s $1.7 million public toilet: “The basic issue is the problem in the blue states is the default is set to make things hard.” John Arnold on Odd Lots: “concentrated benefits, diffuse costs area.”