The News

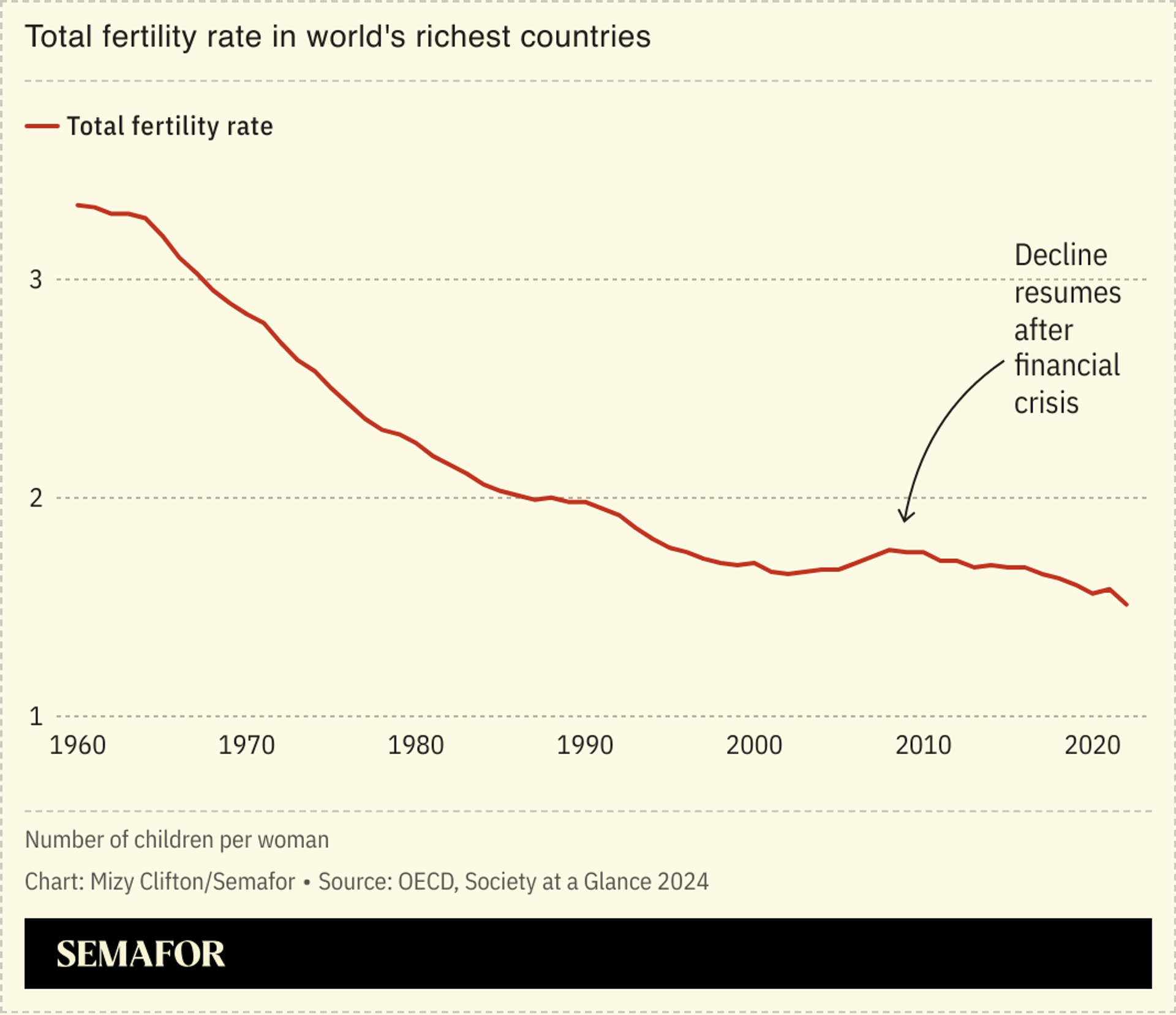

Birth rates in the world’s richest economies have more than halved since 1960 to well below the “replacement level” of 2.1 children per woman in all 38 OECD countries except Israel, according to a new study.

The OECD also found that women’s mean age at childbirth was 30.9.

It recommends policymakers concerned about fertility rates promote a more gender-balanced share of work and childcare responsibilities, and prepare for a “lower-fertility future” where fiscal pressures are stronger — such as by encouraging immigration, supporting longer working lives, and enhancing the productivity of the existing workforce.

SIGNALS

Baby-boosting policies have failed to work

Governments are understandably alarmed by falling birth rates, but their efforts to incentivise parenthood through subsidies and handouts — while often valuable as poverty-reduction measures — are founded on a “false diagnosis” of the problem, The Economist argued, since the bulk of the decline comes from younger, poorer women delaying motherhood and therefore having fewer children overall. Illiberal governments such as those in Hungary and Russia might have no qualms about rolling back decades of efforts to curb teenage pregnancy and encourage women into work, but there’s still the practical problem that few citizens are productive enough to offset the exorbitant costs of baby-boosting policies. Societies need to instead adapt to this new, aging reality, the outlet added.

Concerns over declining birth rates may slide into ethnonationalism

Global population totals have increased despite below-growth fertility rates across the world since the 1970s, thanks largely to migration, according to the UN’s Population Fund. Crisis talk about birth rates may quietly betray a more ominous logic: ”[T]hat if certain birth rates are too low, then others may be too high,” the formulation behind the far-right’s “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory, a columnist wrote in Current Affairs. That higher immigration is rarely considered a solution suggests concerns are ultimately less economic than they are ethno-nationalist, she added.

Women’s bodies risk becoming the battleground

Incentivising birth to fulfill certain collective objectives risks turning women’s bodies into “mere conduits to meet macro demographic targets,” a professor of sociology argued in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs: As an alternative, ”[a] reproductive justice framework… provides a useful lens to think about low birth rate as a social issue, beyond the narratives of heroic mothers saving nations and civilisations,” she added.