The News

The Federal Reserve’s two-year battle against inflation is working. The question now, which sparked yesterday’s stock-market declines, is whether it’s working too well.

Just as it seemed Wall Street and the Fed were on the same page about an interest rate cut in September, a flurry of bad economic news spooked a market already primed for a dip. Investors now worry that the Fed waited too long to take its foot off the brake and tipped the US into a recession.

The spark came from data last week that showed a spike in unemployment and a slowdown in hiring. A handful of concentrated market bets — wagers so reliably profitable lately that confident investors loaded them up with debt — provided the kindling when they unwound quickly. Escalating geopolitical tensions didn’t help. Neither did shaky corporate earnings from Silicon Valley. And it’s all happening during the August doldrums, when trading desks lightly staffed with junior employees tend to shrink from risk-taking.

The result: a swift, sharp drop in tech stocks, a flight to the safety of bonds, and calls from some market players for an emergency rate cut — a rare, unscheduled move between the Fed’s regular meetings.

But the panic had abated by midday, and most major markets were higher by mid-Tuesday. Reset expectations of steeper interest rate cuts look to be staying around, while the panic that accompanied that shift dissipated.

“In terms of phones ringing and investors trying to get a handle on things, we are having our busiest day of the year,” read a note from Goldman Sachs’ trading floor to clients on Monday. “From a trading perspective we are not.”

The firm reported “very little panic” among big investors and blamed the selloff on technical factors, including a surprisingly hawkish one-two punch from the Bank of Japan that foiled one of Wall Street’s favorite trades and sent the Nikkei down 13%. The index bounced back this morning, lending weight to the theory of a glitch.

The US economy is still growing steadily, there are still more jobs than people looking for them, and consumer spending is holding up. Of the 18 economic gauges preferred by the government, more are definitively rising than falling.

Still, the signs are more concerning than a few weeks ago. Unemployment passed a threshold that’s been a reliable indicator of recessions for half a century. Credit-card delinquencies are rising.

Investors aren’t expected to hear from Fed Chair Jerome Powell until the central banking annual huddle in Jackson Hole on Aug. 22, leaving more than two weeks for investors to chew over their concerns.

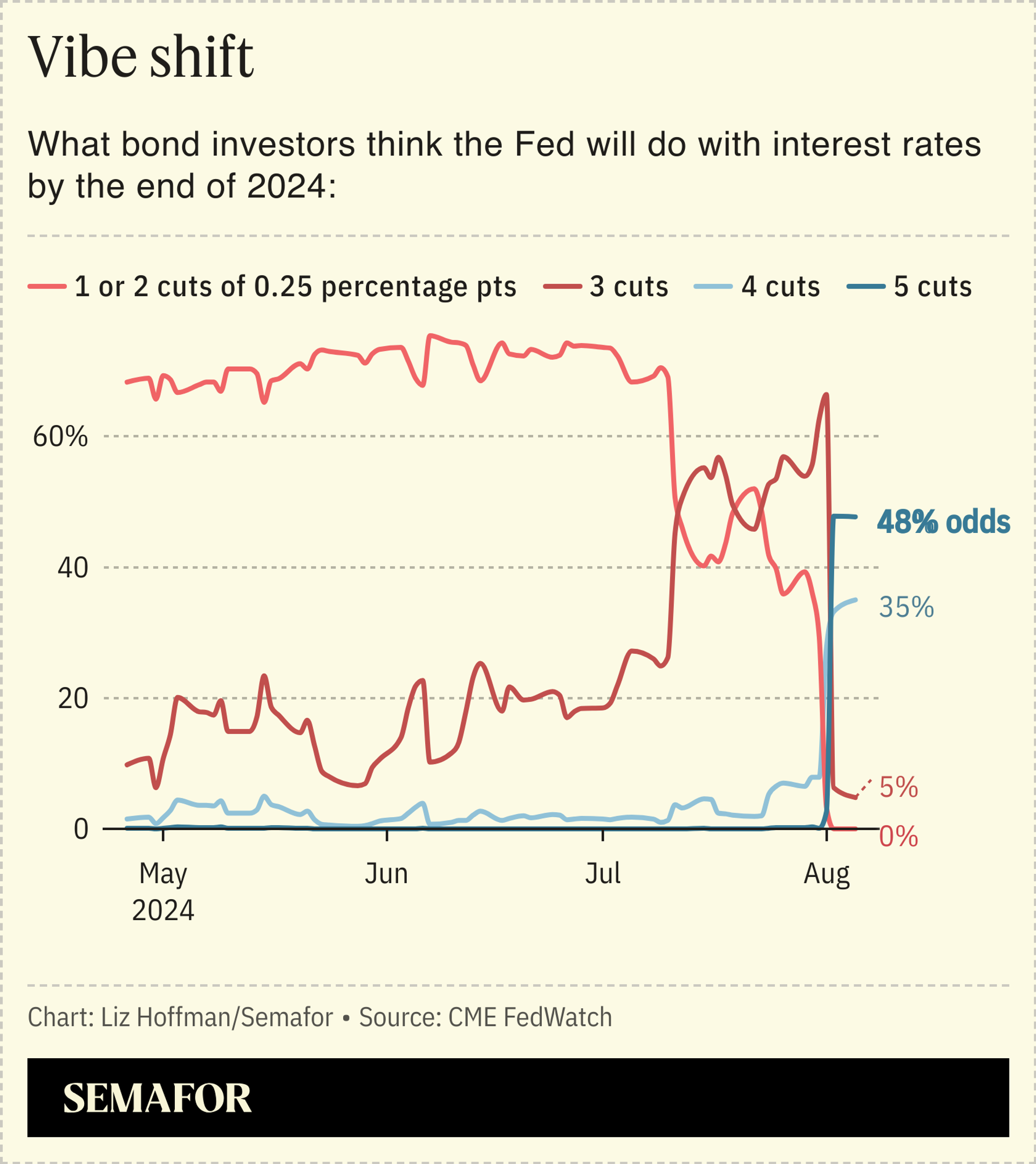

Just three weeks ago, investors were putting 70% odds that the Fed would make one or two cuts of 0.25 percentage points by year-end. Today that bet has no takers, and nearly half think there will be five such cuts (or fewer, bigger ones).

“This is a dangerous game,” said Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY. “Markets are constantly trying to anticipate what a backward-looking Fed will do any time there’s a new data point. A stock-market correction isn’t going to lead them to suddenly pivot, especially without evidence of a pronounced downturn.”

In this article:

Liz’s view

Murky data lets people see what they want, and what Wall Street wants is rate cuts. A lot of business models and investing playbooks don’t work when money isn’t free, and so the wish has been father to the thought for months now.

Investors could just as easily point to strong economic indicators as proof that the Fed should keep rates high. And in fact, when the Fed raised rates in 2015, the people who stood to benefit from higher rates were cheering them on. “I’d go sooner rather than later,” JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon said, after years of low interest rates had crimped loan profits at big banks. The unemployment rate was higher then than it is now.

But investors have gotten used to cheap money. They’ve also gotten used to being rescued. The downturns over the past two decades — the 2007 “quant quake,” the 2008 meltdown, the pandemic, last year’s bank failures — were all severe enough that the government had to step in. There’s no evidence yet that this is more than just a selloff, and maybe a healthy one. Too much money has crowded into too few places, from the Magnificent 7 to the popular yen carry trade to the Great Bet on Calm. Margin calls tend to thin out those ranks.

“When markets go down and [investors] lose money,” Jon Pruzan, the former CFO of Morgan Stanley who is now president of investment firm Pretium, told me in June. “That’s called an economic cycle.”

The View From Donald Trump

The former president was quick to pounce, calling it the “Kamala crash.” Presidents have generally avoided tying their track record to the stock market, which can go down as quickly and capriciously as up. “Former President Trump is the first to do that,” Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi told CNBC. “I’m confused by it.” That could turn into a weakness if stocks rebound, as they are likely to do closer to the Fed’s expected rate cut in September.