The News

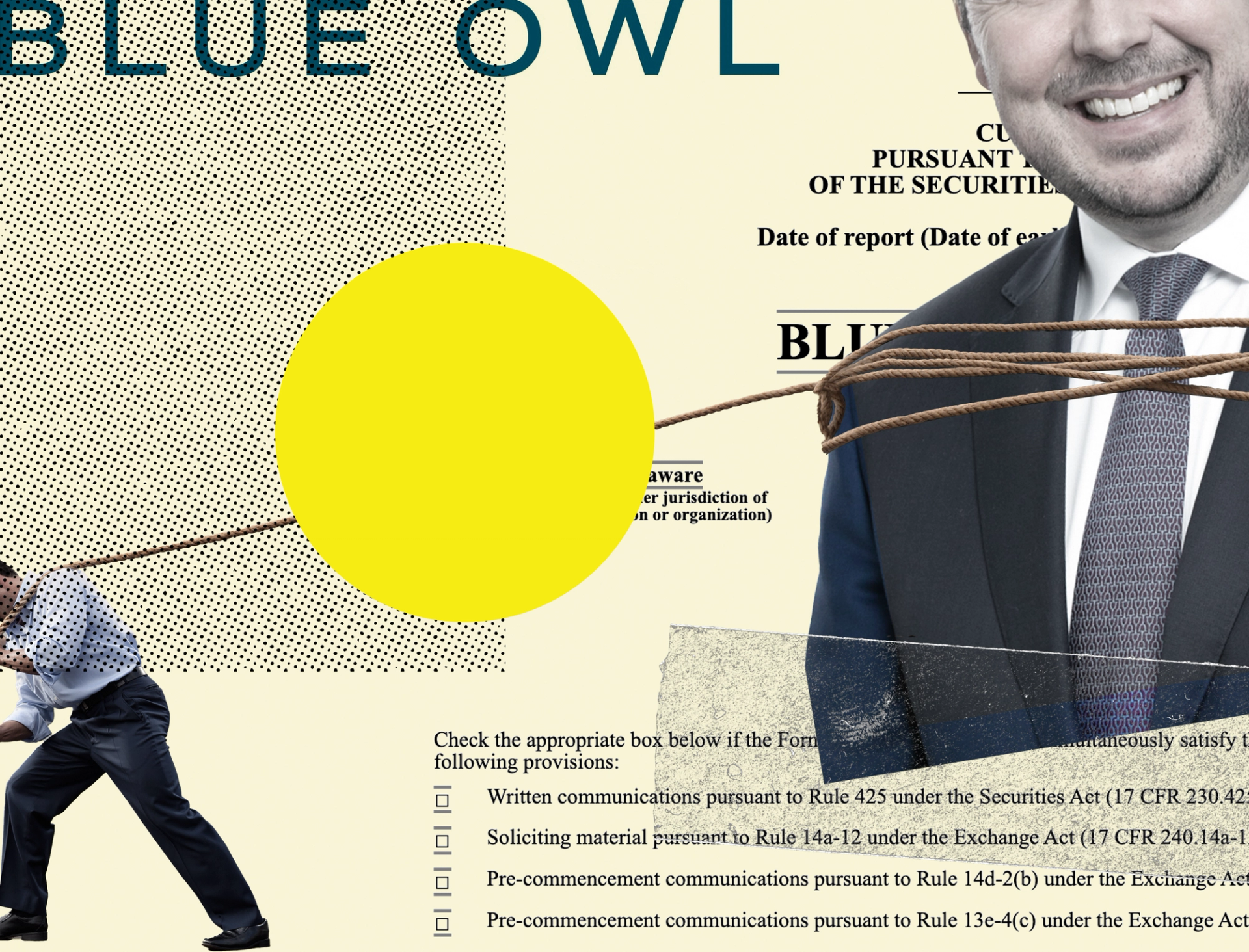

The cost of peace at Blue Owl, the hot-handed investment firm where a civil war erupted this spring: $34 million a year.

Michael Rees, the co-founder who Semafor reported was being pressured to quit, will be paid a quarterly bonus currently set at $8.5 million, according to corporate filings. That number will fluctuate depending on how much money Rees makes for the firm and could rise significantly as his business grows. He’ll take his bonus in Blue Owl stock through 2025.

The rejiggered contracts resolve an ugly internal battle at the top of one of Wall Street’s hottest firms. Rees also gets tighter control over the day-to-day operations of his business, in exchange for a promise to publicly support the firm’s top brass.

Blue Owl was formed from the 2021 merger of Owl Rock, a leader in private lending, and Rees’ business, Dyal, which takes stakes in other investment firms and professional sports teams. A reorganization this spring effectively demoted Rees, who refused requests from the firm’s co-CEOs, Doug Ostrover and Marc Lipschultz, to resign.

Blue Owl declined to comment.

In this article:

Liz’s view

I wrote in June that this all seemed foolish and that there was more than enough money to go around, and it turns out there is. Everybody has a price, and Rees’ was high, but manageable for a firm whose only problem was internal.

In two years, Blue Owl has nearly tripled the money it manages to $150 billion. It’s in the fastest-growing parts of the investing world; private credit is exploding, as is Dyal’s business of cashing out private-equity founders for a slice of their profits.

Ostrover and Lipschultz had few options. The executive-compensation lawyers I asked this spring to look at Rees’ contract said it was ironclad, making it nearly impossible to force him out or fire him.

And having invested most of the $13 billion fund he raised last year, Rees is out raising another one. Investors want to know who will actually be putting their money to work, and turnover in the “key man” tends to send them fleeing. “Blue Owl clearly thinks it can shed Rees while keeping his business,” I wrote. It seems they couldn’t, and sued for peace.

Room for Disagreement

When Blue Owl launched, Rees was a contender to run the firm one day, a serious rise for a former back-bencher who spent his entire career working for others — first Lehman Brothers, then Neuberger Berman. He’ll now have to be satisfied with tending to his own corner. Wall Street is littered with stories of itchy employees being bid back into the fold with big paydays, then leaving anyway.

Notable

- Our June scoop on how Blue Owl cracked.