The Scene

Jerome Powell has said he loses sleep over whether he can successfully steer the US economy to a soft landing, cooling inflation without tipping into recession. The Federal Reserve chairman may rest easier in Jackson Hole, Wyo. this week, where he’s headlining the central bank’s annual Grand Teton confab.

Fed officials were hit with a scare recently with July’s unemployment rate rise, but subsequent data suggests the economy is still growing robustly. The calls from panicked investors have quieted, too.

With inflation receding and an economic expansion apparently on track, the Fed is heading toward a modest interest rate cut in September, likely a quarter percentage point. A serious recession threat would force steeper, faster cuts to stimulate demand, but Powell has little incentive in Jackson Hole to convey such urgency when he addresses fellow central bankers later this week. Instead, he seems likely to project confidence and flexibility.

“I’m not sure that they need to move really fast unless there’s more evidence coming in that the economy really is slowing,” says William English, a Yale professor and the former head of the Fed’s monetary affairs division. “They are kind of getting what they wanted.”

The jobs data had investors chattering about emergency Fed rate cuts to stave off a recession. At 4.3% in July, the jobless rate had climbed by nearly a full percentage point in a little more than a year. In the past, such a rise has almost only happened when the US was in recession.

In this article:

Jon’s view

But the economy’s performance isn’t as dim as the unemployment data suggests. Stock prices have rebounded and S&P 500 companies are on track to report double-digit earnings growth for the second quarter. Adjusted for inflation, the economy grew faster in the first half of this year than it did through the 2000s and 2010s. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates the economy is growing at a 2% annual rate in the current quarter, a bit of a slowdown but still far from recession.

Though companies have trimmed how many new jobs they’re offering, they aren’t cutting existing jobs aggressively. The number of Americans receiving unemployment insurance benefits is historically low — 1.9 million in July, compared with more than 6 million during the 2007-2009 recession and more than 20 million during the Covid-19 crisis.

“I don’t think we’re in recession,” says Claudia Sahm, a former Federal Reserve economist who has observed that recessions almost always accompany a quick half percentage point rise in the jobless rate, as has happened this year. While her “Sahm Rule” suggests a downturn is at hand, she says the jobless rate has been distorted recently by two developments.

Many potential workers remained sidelined after COVID-19, not even looking for jobs. That caused labor shortages and drove the unemployment rate to unusually low levels in 2023. Then, a surge of immigration and an improving economy led to a flood of new job-seekers who were initially classified as unemployed, quickly driving the jobless rate higher.

Know More

While Sahm says recession calls are unwarranted, she argues that the inflation and hiring slowdowns justify Fed rate cuts soon. “I’m concerned they’ve waited too long,” she says.

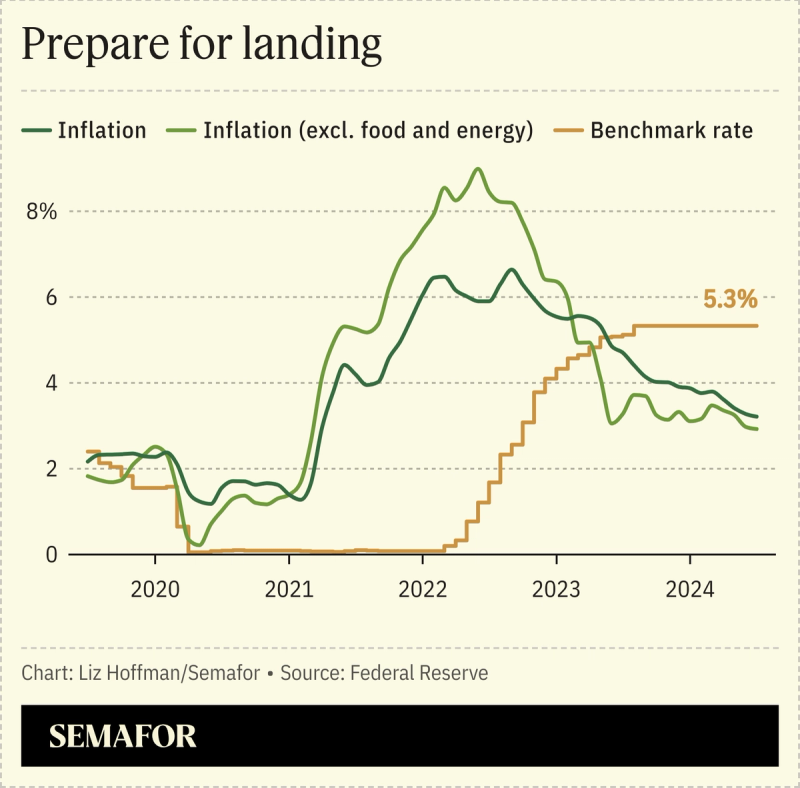

The Fed has maintained its target short-term interest rate at 5.3%, a 23-year high. Economists estimate a neutral rate in the long-run — which neither speeds up nor slows down borrowing, economic growth, inflation, or hiring — is somewhere closer to 3%.

The big question for Powell now is how quickly to get back to neutral. The central bank signaled in June that it expected to cut its benchmark interest rate by a quarter percentage point this year — leaving its target rate at a little over 5% — and then four more quarter-point cuts in 2025. That would bring the target rate to a little over 4% next year. Rates wouldn’t drop to the 3% range until 2026.

The central bank prefers taking gradual, telegraphed steps and adapting as it takes in new data. Recent tame inflation readings suggest the Fed can cut rates sooner than it expected a few months ago — starting in September rather than December — but officials worry that aggressive moves can convey potentially unjustified panic. So quarter-percentage-point adjustments are their default position.

“A sensible position is not to get too worked up,” says Ellen Meade, a Duke University professor and former senior Fed adviser.

Powell is likely to review the central bank’s progress in taming inflation without declaring victory and lay out his options under various scenarios without committing to anything.

He’ll know more after Jackson Hole. A new batch of jobs data will be released on Sept. 6 and the Fed meets a couple weeks later. Until he’s convinced otherwise, Powell’s mindset is likely to be to keep calm and carry on.