The News

China is pouring resources into nuclear fusion research, spending an estimated $1.5 billion — double the US government’s figure.

Beijing has “built itself up from being a non-player 25 years ago to having world-class capabilities,” one nuclear scientist told Nature, with ambitious timelines: It hopes to build a one-gigawatt test reactor in the 2030s and a prototype power plant within a few decades after that.

ITER, the huge multinational fusion collaboration based in France to which China contributes, will not begin experiments until 2039, 19 years behind schedule. China’s rapid expansion is also pushing global science forwards, say advocates, who hope fusion will one day provide limitless green energy.

SIGNALS

China still faces hurdles on energy self-sufficiency

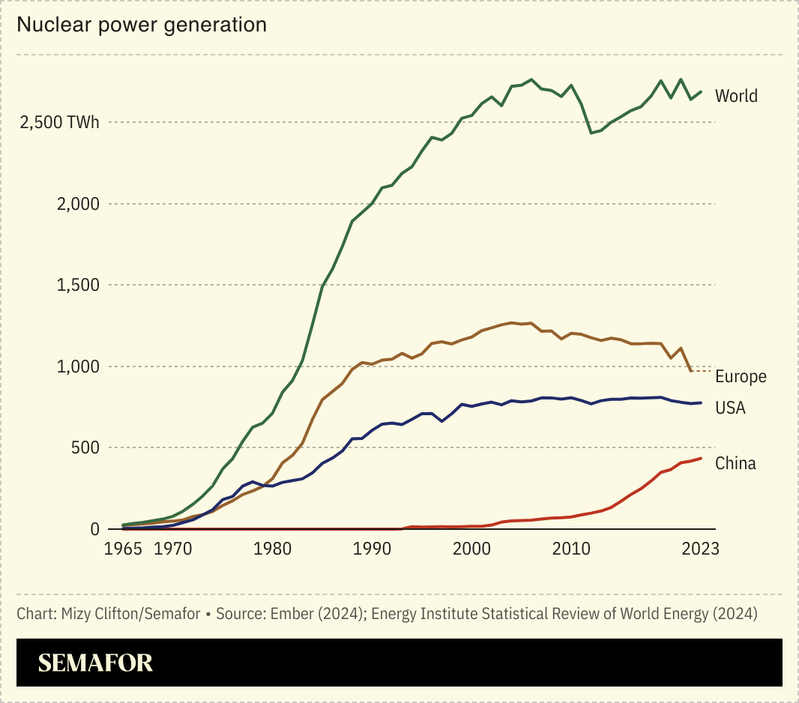

China is expected to overtake France as the country with the second-largest nuclear power capacity by 2026, and could surpass the US within the next decade, The Diplomat noted. Beijing’s ambitions are about geopolitics as well as climate change: Conflicts including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have thrown into sharp relief the importance of energy self-sufficiency, and China — a long-term net energy importer — wants to reduce its reliance on oil and gas. But despite being mostly self-sufficient in the design and construction of plants, China still suffers from a shortage of in-house specialists, and hasn’t yet built out the infrastructure needed for other aspects of the supply chain, nor faced down public opposition, the Financial Times reported.

Beyond China, infrastructure and skills shortages are hampering progress

Nuclear energy is controversial among climate advocates: Greenpeace, for example, argues that the climate “emergency” simply can’t wait for the construction of nuclear power plants (which take on average 10 years to build). Building plants is so slow in the West partly because countries lack the necessary infrastructure and skills, The Economist argued, which in turn deters investment because there is no guarantee of timely returns. Despite newfound “positive momentum,” progress remains slow, and stakeholders need to develop industry-wide best practices for scaling up all aspects of the supply chain if they are to get out of this vicious cycle, McKinsey & Company experts argued in 2023.