The News

BERLIN — Germany has long been a global wind power leader, but a slowdown in expansion and an effective campaign from the far fight threatens to dent its reputation for clean energy.

The Alternative für Deutschland party has made its NIMBY-like opposition to wind a central plank of its platform, pushing the debate over renewable energy to the forefront ahead of three state elections in eastern Germany. The AfD could finish in first place on Sunday in two of those states — Saxony and Thüringia — which were once part of the communist German Democratic Republic.

Some elements of their anti-wind playbook are similar to right-wing talking points in the US or elsewhere in Europe. (Donald Trump this week said wind power “kills the birds, it destroys the fields.“) But in marrying populist talking points with arguments that appeal to simmering local frustrations about clean energy, the AfD’s campaign has developed a novel tactic that seems to have caught on with the electorate.

“If you consider why people consciously or unconsciously decide to live in the countryside… then the quality of life of these people is impaired by the wind industry,” Nadine Hoffman, a member of the Thüringen state legislature and the AfD’s local spokesperson for environmental and energy policy, told Semafor. “The rejection is natural.”

Know More

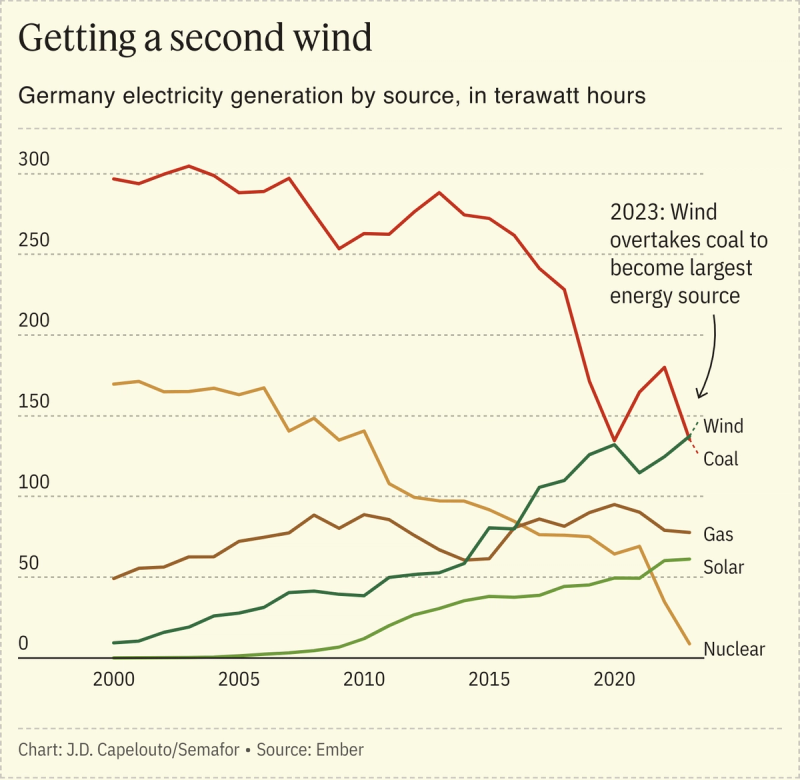

More than a third of Germany’s active wind turbines are located in the smaller but less densely populated east, which includes Saxony and Thüringia. Wind overtook coal last year to become Germany’s top electricity source, generating nearly 30% of the country’s power. But expansion has slowed, with wind generation set to grow by only 1% this year, largely because of weaker wind speeds and a construction slowdown.

The AfD, perhaps best known outside of Germany for its anti-immigration and euro-skeptic stances, opposes the broader energy transition and denies man-made climate change — but the party’s pledges to stop wind power specifically has featured most prominently in its campaigns in the east.

Compared to other elements of the energy transitions like solar farms or electric vehicles, nothing energizes right-wing German voters quite like wind: Only about a quarter of AfD supporters in eastern Germany support wind power, while about half oppose it, according to a recent study from the German Economic Institute.

A 2021 study found that areas of Germany where new wind turbines were built were likely to see a boost in support for both the fiercest critics and backers of wind power: The AfD and the environmentalist Greens.

Solar, meanwhile, has not been politicized in the same way by the far right. New reforms have helped push German solar energy generation to a new record, and even as rural eastern Germany becomes dotted with solar farms, voters don’t seem to mind. Most AfD supporters in the region support solar energy, despite the party’s official stance against it, the economic institute study found.

“The impact of a wind turbine is not only visually much greater than that of a solar system,” the AfD’s Hoffman said, explaining why more people hate wind turbines compared to solar panels. “You only have to look at the huge foundation that seals the ground. Solar systems are also not subject to bird strikes like wind turbines.”

J.D.’s view

Far right opposition to renewable energy, in Germany or elsewhere, isn’t a new phenomenon, but the AfD’s campaigns in the east are notable for how they have sought to politicize wind power specifically. By seizing on a particularly visible issue in rural Germany — where the average voter is more likely to see wind turbines on any given day — the AfD made wind one of its defining issues by pairing its anti-establishment stance with its climate message.

If the party gains more power and is able to slow down wind expansion, it would be a bad look for Germany’s clean energy bonafides, and could give ideas to populist actors in other countries that are expanding renewables.

Even if the party is not able to form any state governments, it could become “sand in the gears” of climate efforts by opposing renewable energy infrastructure projects and “by pushing mainstream parties to have more cautious stances on renewables,” said Manès Weisskircher, who leads a research group at Dresden University of Technology studying the climate policies of far-right groups.

Instead of just railing against the climate movement or calling climate change a “hoax,” the AfD has gotten hyper-specific around wind energy infrastructure. The party employs many typical anti-wind arguments, many of which have been debunked or are unverified: That turbines are noisy, harm birds, contaminate the ground, and produce low-frequency sounds called “infrasound” that cause sickness.

But its most successful pitch opposes wind turbines in forested areas and near homes. Last year, the AfD teamed up with the conservative party of former Chancellor Angela Merkel to pass a law in Thüringia making it more difficult to build wind turbines in forests, despite the objections of the current left-wing government.

“Wind energy is also likely to have negative consequences for tourism, because who comes to the Thuringian Forest to marvel at industrial plants?” Hoffmann said.

The AfD’s rhetoric has been particularly successful in eastern Germany, a major producer of lignite, because the region has been especially impacted by the country’s pledge to phase out coal by 2038 in favor of renewables.

Voters there have already endured a vast transformation after German reunification, which was marked by unemployment and population decline in the east. Mainstream political parties have had a difficult time pitching rural communities on the shift to renewables, leaving room for populist parties to swoop in.

“There is this sentiment that is activated by populist actors that the energy transition is sort of forced upon them by the government in Berlin that is run by Western Germans, mainly,” said Matthias Diermeier, a researcher at the German Economic Institute. “People in eastern Germany… have the feeling that they have been in a transition period for 35 years.”

The View From The rest of Europe

A rollback in wind energy in Germany, a vanguard of the energy transition in Europe, would buck a broader trend seen throughout the continent, as many other European countries take steps to loosen constraints on onshore wind.

The UK’s new Labour government, for example, recently lifted the country’s de facto ban on new onshore wind farms. Even some countries with right-wing national governments, like Hungary and Italy, are showing more openness to wind, easing the planning and permitting process, said Conall Heussaff, an energy and climate research analyst at the Brussels-based Bruegel think tank.

But the effective populist politicization of wind power in Germany could serve as “a kind of case study for other similar political entities to try to use onshore wind as a way to further create a wedge in political discourse,” Heussaff said. The French far-right National Rally party, for example, similarly opposes the expansion of wind power.

Room for Disagreement

On the federal level, Germany is still investing heavily in wind and other renewables. Recent permitting reforms have made it easier to build turbines, and the country is deploying more renewables than others in Europe, Bloomberg reported this week.

The power of the states is limited, so even in the unlikely event that the AfD is part of a government in Saxony or Thüringia, the party would have to overcome a lot of hurdles before it comes close to fully reversing the country’s energy transition.