The Scene

Little has changed four years after the CEOs of America’s biggest companies promised a more egalitarian approach to business, according to a Semafor analysis of corporate filings.

The splashy 2019 commitment from the Business Roundtable and its 181 CEO signatories redefined the “purpose of a corporation” as more than just a blind pursuit of profits.

Yet corporate spoils are still shared overwhelmingly with shareholders, not employees. While executive compensation wasn’t specifically called out in the pledge, CEO pay has continued to soar, outpacing raises handed out to hourly workers, less out of generosity than a post-pandemic scramble to hire workers.

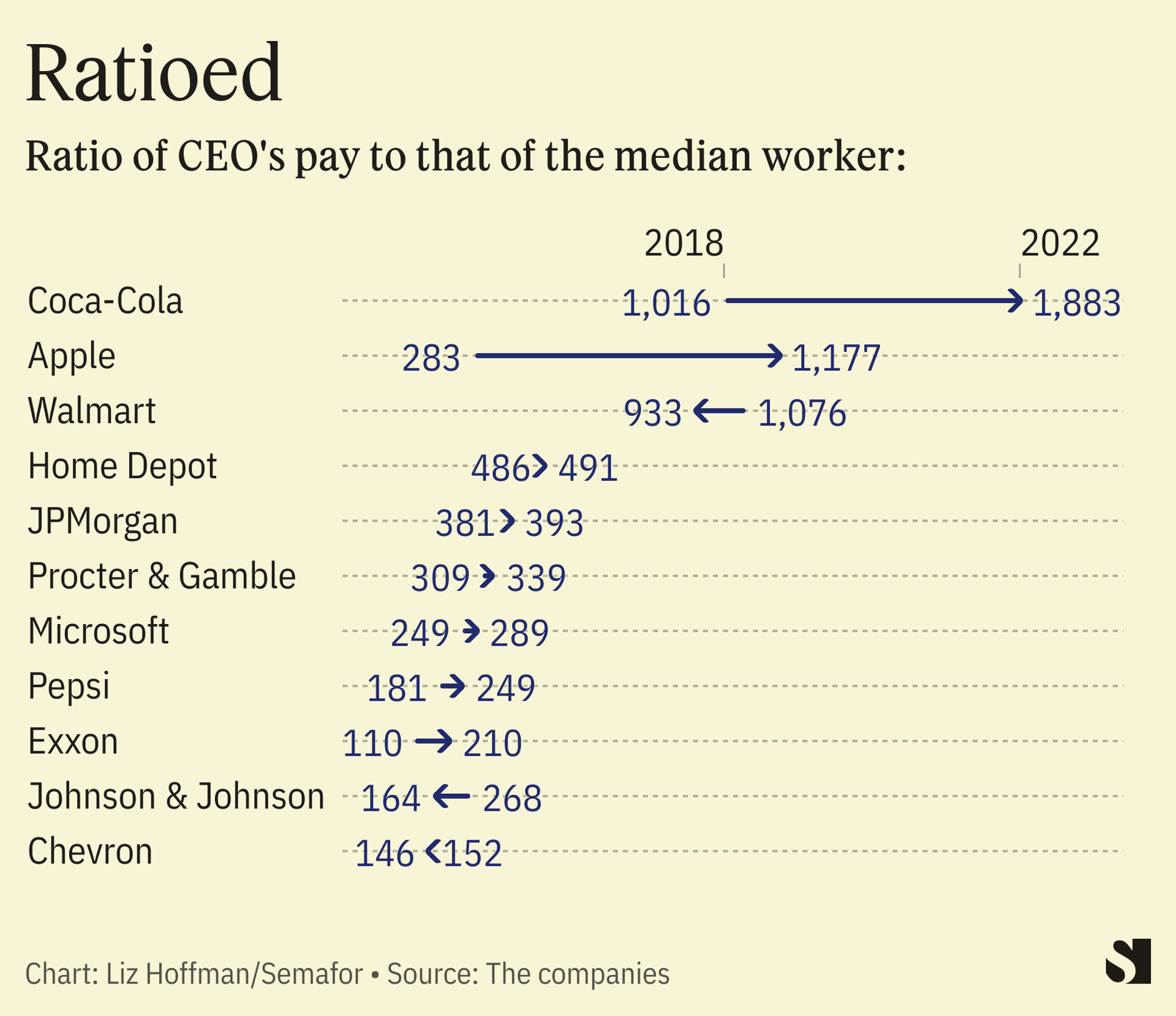

In 2018, the year before the BRT made its commitments, the average CEO made about 140 times what his or her average worker took home. Last year, that ratio was 186 to 1.

Among the BRT’s 20 largest firms, CEO pay has risen from 324 times that of the median worker in 2018 to 441 times in 2022.

Twelve of them spent more of their free cash flow last year buying back stock than they did five years ago. Six, including Exxon, Procter & Gamble, and Coca-Cola, spent less on physical investments and technology in 2022 than in 2018, despite soaring profits. Six now have lower ESG scores from S&P Global than when they signed the BRT statement.

The Business Roundtable meets next week in Washington with a more earthly agenda as corporate bosses worry about rising tensions with China, push for reforming the permitting process for big infrastructure projects, and lobby for retaining expiring tax benefits.

In this article:

Liz’s view

I think CEOs mostly meant it in 2019. Their failure to follow through says a lot about the cold wind that’s swept in the past two years through a business community that is desperate to drop the do-gooderism, quit getting yelled at by Vivek Ramaswamy, and get back to business.

Larry Fink has dialed back the ESG talk after becoming a target of conservatives. Salesforce ditched its “wellness culture” for one of “high performance,” and CEO Marc Benioff has stopped touting his liberal politics. At Davos this year, executives were largely absent from the conference’s virtue-signaling, Ukraine-toasting, turnip-juice-guzzling mainstage, packing their schedules instead with client meetings in cloistered hotel suites.

Marc Pritchard, Procter & Gamble’s chief brand officer, said last year that companies have “gone a bit too far into the good” at the expense of growth, and entrants at this summer’s Cannes Lions advertising awards were advised by one juror to dial down the politics and focus on “selling shit.”

A development that feels closely related: Nearly a third of those who joined companies in diversity-related roles after the 2020 death of George Floyd — which spurred a flood of statements and new goals from big companies — have already left, according to Live Data Technologies, which tracks employment trends.

The corporate softening of the 2010s, when CEOs set diversity goals and shared dog photos on Instagram, feels like a relic. It was hustled along by the #MeToo movement and hit a gauzy peak during 2020, with the pandemic and widespread racial-justice protests. A wave of anti-Asian violence and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were also morally unambiguous issues on which to take a stand.

But today’s questions are more deeply divisive — see: Bud Light boycott— and CEOs are all too happy to stick their heads back below the parapets.

Room for Disagreement

The S&P 500 ESG index, which excludes about a third of the S&P 500 index for one unsavory practice or another, has beaten the market each of the past four years, so there’s clearly value in standing for something.

And over the past few months, companies have trimmed buybacks in favor of physical investments, suggesting a longer-term view of value.

Notable

- “When did Walmart grow a conscience?” The Economist on corporate makeovers that would make “Milton Friedman turn in his grave.”

- The BRT’s 2019 manifesto that started it all.