The News

Wall Street is gearing up for the next battle over U.S. investments in China, worried that Congress will out-hawk the White House and impose harsher limits that would ban a host of client services.

In August, the White House issued an executive order restricting money flowing to China in semiconductors, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence — all key for the country’s military and intelligence agencies. The Treasury Department is turning that order into tailored rules governing equity stakes, debt financing, and joint ventures.

Mike Gallagher, chair of the House select committee on China, told Semafor that approach leaves too many loopholes and uncovered sectors that could still give Beijing an advantage. He said that meetings with financial executives and investors in New York last week left him more convinced that the U.S. needs a wider approach — backed by legislation, not just the kind of agency rule-writing that is a common Republican punching bag — that goes farther than the Biden administration’s efforts.

Wall Street lobbyists want Democrats to take the initiative in Congress, hoping to keep any legislation more in line with Treasury’s proposal. So far they haven’t seen signs of that happening. If anything, Gallagher’s swing through New York last week boosted his credibility and momentum, stoking fears China hawks could get their way.

Even if a Republican-led bill is “more hawkish than what Wall Street would devise on its own, they can live with it as long as there is certainty,” Gallagher told Semafor, ”[as long as] we’re not just at the whim of a particular president, and there’s a glidepath to transition to the new rules.”

Know More

Rep. Patrick McHenry, the Republican chair of the House Financial Services Committee, has been skeptical of both the White House’s approach and congressional action, seeing both as heavy-handed government intervention. He’s even suggested using Congress’ power to hamstring the White House’s order.

“To outcompete China, we cannot become more like the Chinese Communist Party,” McHenry said at a hearing last week. “We must double down our commitment to free people and free markets.” He supported using Treasury’s sanctions watchdog, called OFAC, to stop investments that threaten U.S. security, suggesting a more company-specific approach.

Financial firms wary of new restrictions may find comfort in the fact that a divided Congress has trouble accomplishing much beyond what absolutely needs to get passed to keep the lights on in Washington (think the current government funding battle).

The idea of imposing restrictions on investments in China has bipartisan support, but past efforts have faltered.

Liz’s view

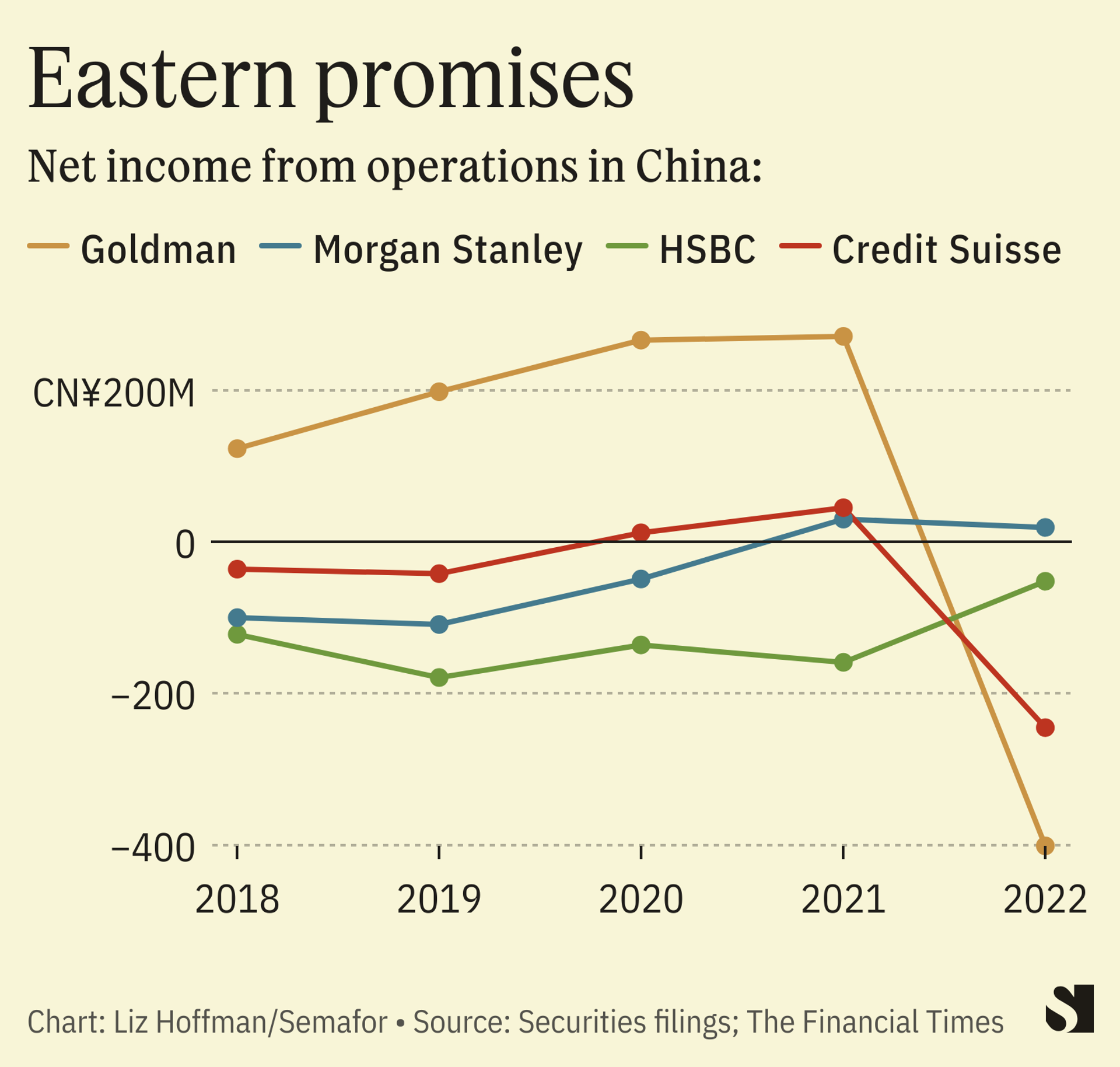

I think the concern is less about immediate profits; with the rare exception, mostly in venture, Western financial firms lose money in China and have for years. And the fees they do make, mostly from taking Chinese companies public on western exchanges, are already under threat — not from Washington but from Beijing.

That’s unlikely to change as China grapples with slowing growth and a wobbly property sector, which contributes as much as 30% of the country’s economic output.

But overly broad rules drive Wall Street crazy because of the cost to comply with them and the penalties for even unintentional mistakes. And as I wrote last week, economic retrenchment is just generally unnerving for the financial set, whose careers have been carried, and fortunes minted, by a world that was steadily liberalizing.

When JPMorgan laid out the four planks of its model, “global” was number two. Goldman Sachs bills its $2.7 trillion asset-management arm as “global, broad, and deep.” They have no idea what to do if that reverses.

The View From U.S. businesses in Shanghai

“2023 was supposed to be the year investor confidence and optimism bounced back after years of Covid disruptions and restrictions,” reads a report this week from the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, which promotes U.S. business interests in China.

Instead its members painted the bleakest picture in decades, with just over half saying they were optimistic about the next five years. Those in logistics, technology and management consulting were especially negative as China’s crackdown on intelligence industries continues. “Many have reevaluated their basic assumptions” about doing business on the mainland, the report said.

Notable

- Check out the full survey results from AmCham in Shanghai, with one-third of respondents saying policies and regulations toward foreign companies had worsened in the last year.