The News

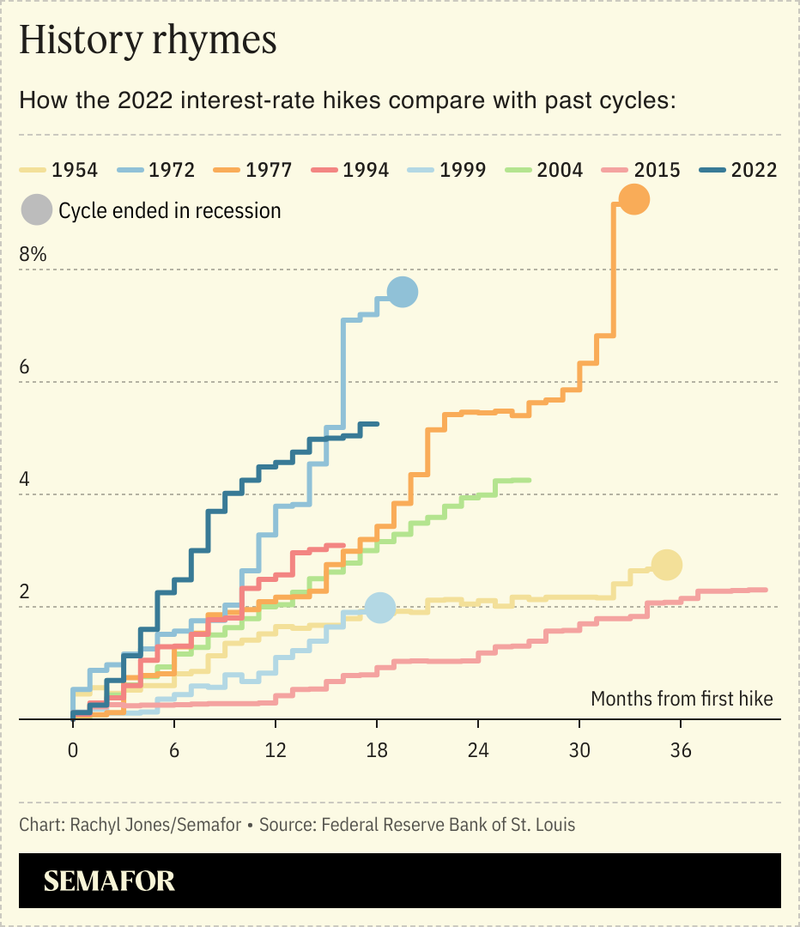

The Federal Reserve has begun its great descent from the monetary mountain, having threaded an historically small needle: Most steep rises in interest rates since World War 2 have ended in a recession. That could still happen in the US, but for now there are enough jobs for most people who want one, inflation has cooled, borrowing costs are falling, and the economy is growing.

Austan Goolsbee is the president of the Chicago Fed.

Q&A

Can we declare victory on a soft landing?

That’s a little misleading because it connotes a stopping point. It was an achievement for the US and other major economies around the world in 2023 to bring inflation down — almost as much as it’s ever come down in a single year — without a recession.

Now we’re in a second part of the job, which is trying to freeze the economy where it is right now. Inflation coming in around 2% and unemployment at 4.1% with GDP growth of 2.5% or 3% is a lovely place to stop. The challenge is, can we engineer that as a steady state, or are we going to crash through?

How sacrosanct is that 2% inflation target? Why not just declare victory at 2.5%?

Totally sacrosanct. When the Fed announced the 2% inflation target in 2012 and made it official, I was critical because I thought it was overly precise for a data series with a lot of noise in it. But that is now a sacred promise, and I will say that I’ve come — if not a full 180 degrees, maybe 178 degrees on this. The target was an anchor when inflation surged and kept things from spiraling.

You said recently that you think inflation may possibly come in under 2%. How realistic is that?

It’s not my most probable outcome. But if you look at the three-month inflation, it’s under 2. It’s not inconceivable in the way it was a year ago.

I was surprised at how quickly the debate turned in August between being worried about inflation to being worried about jobs. Can you shed any light on the Fed’s thinking?

The way I think of it, and I’m only allowed to speak for myself, is that it’s not about individual data points. I understand why it’s the market’s business model to — I hesitate to use the phrase “overreact” — but react in a really extreme way. We get a disappointing jobs number, and you’ve got people going on TV saying we need to cut 150 basis points. And then we get a strong jobs number and they say we need to raise.

There was a long period of time where we were focused almost exclusively on inflation because we had to be. We’ve moved out of that period to a more normal [focus] on both sides of the mandate and trying to figure out the trade-offs.

The through-line for the last year and a half has been steady progress on inflation. Now it’s coming in right around 2% and the job market is cooling from overheated levels to something like steady-state full employment. If you’ve got both sides of the Fed’s legal mandate — the stabilization of prices and the job market at full employment — then you’d better be careful having the interest rates so much higher than where anyone thinks is normal.

If you had said, before the pandemic, that the Fed is going to raise rates 500-plus basis points in a single year, most people would have predicted deep recession, if not collapse. And that didn’t happen.

Why?

One: Normally, the cyclical things are also the rate-sensitive things, like housing and cars and construction. So when it’s overheating, you raise rates and it tends to slow down. This time, not going to the dentist or going out to a restaurant — that was what drove the recession. Those are less rate-sensitive. So that scrambled the transmission mechanism.

Two: We think of housing as one of the most interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy. But there’s been a fundamental shift since 2007 in the share of mortgages that are 30-year fixed mortgages. There used to be much higher usage of adjustable-rate mortgages, and so the transmission mechanism of monetary policy was faster.

To go back to something you said last year about the timing of rate cuts and the danger of waiting too long: We’ve pulled the turkey out of the oven. How worried should we be about residual heat?

The hardest thing a central bank does is get the timing exactly right at moments of transition. I’ve gotten to know Chair Powell pretty well, and he is a first-ballot Hall of Fame Fed chair. He has shown astoundingly good judgment. The question now is: We had a lot of increases in rates and we held them high for a long time, and how much that cumulative tightening is still coming through?

Let’s talk about Fed independence. We heard what Donald Trump said, but Democratic politicians were publicly calling for rate cuts, too. What do you make of all that?

Countries where the central bank is independent, where the sitting administration does not get to dictate what the interest rate should be, have lower inflation rates, higher growth, lower unemployment. The outcomes are a lot better. I think it’s a bad idea to contemplate a system where the Fed is not independent.

But isn’t there an argument for the Fed to be more tethered to politics? For example, that third round of pandemic stimulus was not your decision but it made your job harder by fueling inflation.

Those seem like two different questions to me. One is: can the sitting administration dictate what interest rates? The research is very, very clear on the outcomes. There’s a second question: Would it be appropriate for the Fed to be weighing in on government policy? I think that’s a bad idea. It’s like my Midwest motto: “There is no bad weather. There is only bad clothing.” The Fed’s job should be: you tell us the conditions, and then we will react.

No matter who wins, tariffs are going to be a major part of the next 5 or 10 years. What do you think is the right size and shape of those?

Like every other economist, I am not a fan. That said, if Congress wants to pass tariffs, they’re perfectly free to do that. Tariffs raise prices. And if they affect prices, then it affects the dual mandate. But we react to the conditions, not to the policy.

On antitrust: is the economy overly concentrated?

I think there has been an increase in concentration and market power. That’s different from: did that cause inflation? Markups vary a lot over the business cycle. I think there are a lot of industries where the evidence is pretty strong that market power has risen, but you’ve just got to be careful applying that to the aggregate economy.

One of the Fed’s jobs is ensuring maximum employment. How are you thinking about AI?

If AI holds out the promise of productivity growth increases, that does endanger employment in some sectors where productivity growth is so high that they don’t need people to do those tasks anymore. But the 150-year history of technological progress feels like if you get productivity growth that fast, our incomes are going to go up, there’s going to be very robust growth without inflation, and there will likely be a whole lot of job openings in sectors that do not yet exist. That’s the history of automation and technology replacing employment.

But you don’t think AI is coming for all of our jobs and society is going to collapse?

If in 1915 you had told people how many phone lines there would be in the future, they would say every man, woman and child in America would need to be a telephone operator, and so it’s impossible. The fact that we had that many phone lines and employment did not go to zero even in the telecom sector, is kind of instructive.