The Scoop

BlackRock is under fire from a federal agency, which is itself a target of Washington scrutiny, over its influence in corporate boardrooms. It’s fighting back.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. wants to impose sweeping limits on how giant asset managers invest in US banks. The agency’s concern is that BlackRock, Vanguard, and other big money managers wield too much influence over lenders that decide what gets built in America.

The effort has the rare backing of both Republicans on the FDIC, who think giant asset managers are too liberal, and Democrats, who think they’re simply too big. Two defining forces in corporate America — concerns over “wokeness” and monopoly power — are colliding, and the ensuing fight is likely to touch on a third: private-sector backlash against expanding regulatory power.

The FDIC’s proposal to BlackRock and Vanguard, delivered Oct. 4, would bar them from trying to influence a bank’s behavior by, for example, nudging it away from financing oil projects — a nod to the past ESG priorities of BlackRock CEO Larry Fink. It would also require them to disclose any conversation their employees have with bank executives, and to notify the FDIC every time they acquire more than 10% of the shares of a bank — a level BlackRock already holds at about 40 lenders, people familiar with the matter said.

The FDIC “may request such additional information at its discretion,” the draft agreement says, which has left executives concerned that they’re signing up for a new permanent overseer. The agency set an Oct. 31 deadline for BlackRock and Vanguard to sign the agreements limiting their actions.

Without a deal by that date, BlackRock and Vanguard could be forced to sell hundreds of millions of dollars worth of bank stocks — not ideal for a sector still bruised from last year’s mini-crisis. The agency can extend the deadline.

BlackRock executives pushed back in a call with FDIC staff in recent days, the people said, arguing the rules are unworkable for funds that trade in and out of positions frequently to match indexes. Some of the rules would kick in at a 5% stake, which both BlackRock and Vanguard, because of their sheer size, hold in nearly every public company.

The push shows how FDIC Chair Martin Gruenberg, who agreed in May to resign after an investigation found pervasive sexual harassment at the agency, is determined to govern right until the end. He has also proposed new rules on deposits and is holding up a rewrite of new bank rules for being insufficiently strict, Semafor has reported.

On the asset manager front, current rules allow investors to own big stakes in banks so long as they remain passive — although, as Jonathan McKernan, the Republican FDIC director who proposed the new rules in January, has pointed out, it’s a loose system of self-reporting.

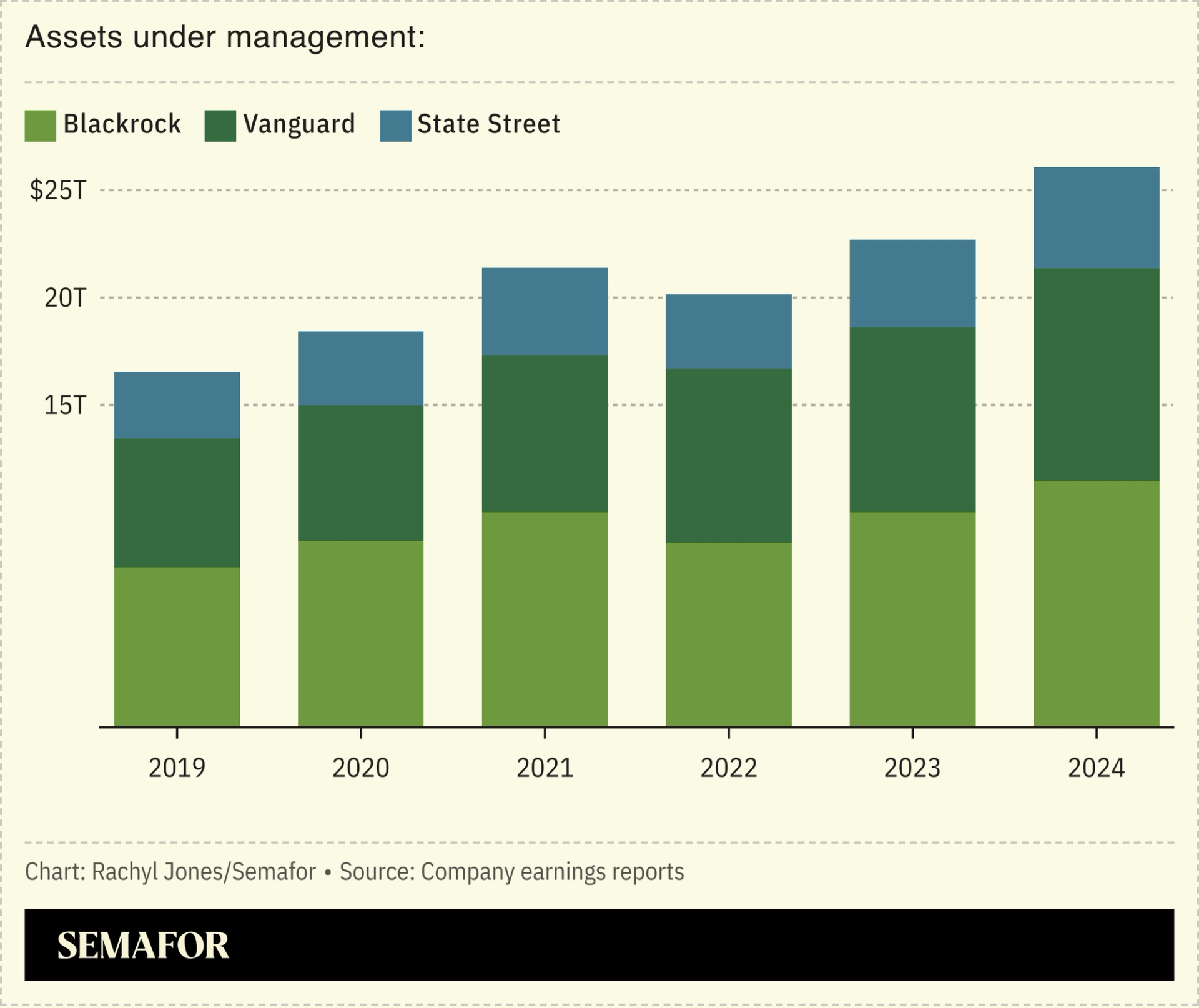

“The Big Three purport to be merely passive investors, but a growing body of evidence suggests that’s not always the case,” he said in a speech earlier this year, referring to BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street.

The FDIC and BlackRock declined to comment.

A Vanguard spokesman said: “Consistent with our mission and passive approach, we have taken strong actions, engaged with policymakers, and suggested additional reforms that further clarify and refine expectations around passivity.”

In this article:

Liz’s view

This seems like a solution in search of a problem. By BlackRock’s own tally of its voting record, which is publicly available, it sided with management in 1302 of 1304 items that appeared on banks’ annual ballots since 2022, according to a letter it sent to the FDIC seen by Semafor. Over that period, it bent the ears of executives over some issue or another at just 12 banks. BlackRock engaged with 1,662 companies over the first half of this year alone. (To be fair, the fact that it was able to give the FDIC those numbers suggests that monitoring those meetings would not, in fact, be all that onerous.)

But more broadly, BlackRock is getting out of the business of pushing social causes on corporate boards as quickly as it can. It dropped out of an alliance committed to cutting carbon emissions and made it easier for fund investors to vote their shares according to their own preferences. As the mood around ESG has soured over the past two years, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, once its most vocal proponent, has gone all but silent on the topic. Vanguard, which was only ever lightly in moralizing business, has also backpedaled.

When then-Sen. Pat Toomey published a report in 2022 that accused BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street of using “investors’ money to advance liberal social goals,” he may have had a point, though a quickly dulling one. When the House Judiciary committee accused them of being part of a vast left-wing conspiracy, it didn’t.

In 2021, BlackRock voted to require JPMorgan to conduct a racial-equity audit, over Jamie Dimon’s objections. This year, JPMorgan’s cause-cluttered ballot included measures on racial equity, carbon emissions, indigenous people, human rights, and animal welfare. BlackRock voted against all of them.

Room for Disagreement

“BlackRock’s extensive voting guidelines are all about governance. I’m not sure there’s a way to be a truly passive investor if you’re voting on director independence, over-boarding, etc,” said Alex Thaler, CEO of Iconik, which makes software that helps shareholders vote their shares. “Every vote expresses a preference about how to create value or align with values. You can’t get away from that.”