The Scoop

KKR owes $2.5 billion to Goldman Sachs’ richest clients, a tab that stems from an unusual provision in a 2021 deal and that is only getting bigger.

Two years ago, KKR bought Global Atlantic from Goldman for $4.7 billion, hoping to make it the core of a push into insurance. It bought the insurer not in a fund with outsiders’ money, as is typical for private equity, but on its own books, and it counts Global Atlantic’s profits as its own.

Not wanting to overstretch financially, KKR bought just 63% of the company. Much of the rest ended up in the hands of clients of Goldman’s private bank, where the minimum account size is $10 million.

The deal included an unusual provision: Those minority shareholders can force KKR to list their shares in Global Atlantic in a few years, or find another way to buy them out, people familiar with the matter said.

The buyout shop considers Global Atlantic central to its future and is unlikely to let it go, meaning it would have to buy back the other 36%.

In the meantime, the price tag to do so is only going up. KKR in June valued its own stake at $4.4 billion, which pegs the minority stake at $2.5 billion. At its current stock price, KKR would have to issue 42 million shares, about 5% of its existing share count.

The clearest mention of this predicament in KKR’s 414-page annual report to investors is this line: “in connection with other investments, we may make certain future contingent payments in the form of common stock.” Of course, KKR could borrow to buy out Goldman’s clients or find another, more patient investor to step in.

“It’s not an open-and-shut case, but the optics could be better, for sure,” said Shivaram Rajgopal, an accounting professor at Columbia. “Forget the lawyers. Tap a smart person on the street and ask ‘does this make sense to you?’ and I think businesses have an obligation to listen to that.”

Disclosure obligations are “a little murky when someone has a strategic plan and knows it will cost them money but has the flexibility not to do it,” said Robert Evans, a capital-markets lawyer at Locke Lord, who noted that KKR could simply float one-third of Global Atlantic. “It may only become a thing when there’s a board resolution or an offer is launched.”

A KKR spokeswoman declined to comment beyond corporate filings. KKR co-founder Henry Kravis is an investor in Semafor.

In this article:

Liz’s view

KKR could have issued new shares back in 2021 to buy all of Global Atlantic. But CEOs are optimists. When given the choice between dilution now or dilution later, they will always choose later, assuming their stock will be more valuable then. And shareholders don’t like deals that dilute them, and it was almost certainly easier to kick the can.

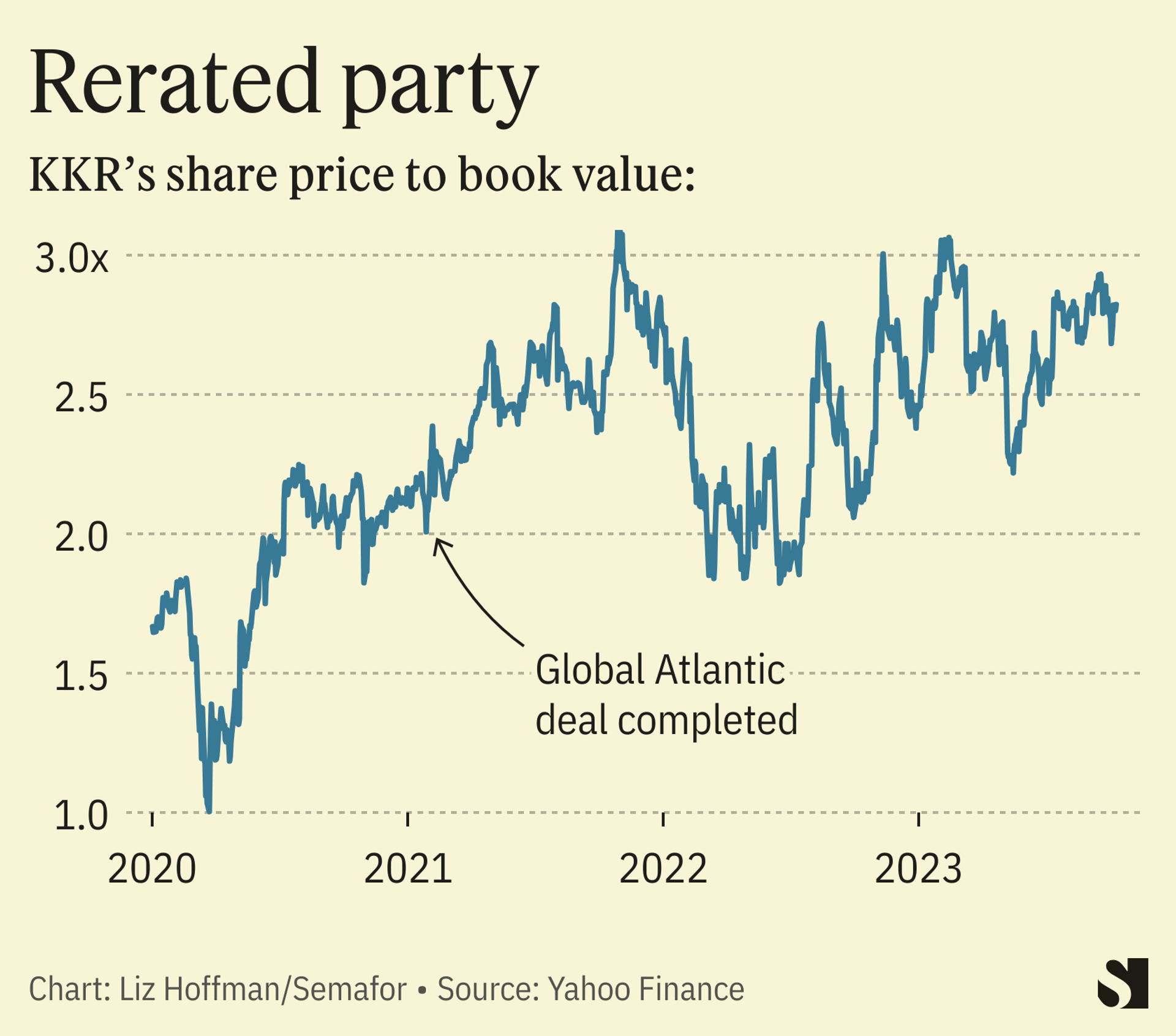

That was a good bet for KKR: When the deal was struck, its stock was trading at twice its book value. Today it trades closer to three times, meaning the company would have to issue fewer shares to come up with the cash.

But if I were a KKR shareholder, I’d want to know that this dilution risk is out there. Maybe they do — institutional investors have a lot of analysts and do their own work — but it’s another reminder that in a growing sea of corporate disclosures, important things are often hard to find.

Room for Disagreement

This isn’t so unusual: Apollo did the same multi-step maneuver in its acquisition of its own insurance arm, Athene. It doubled its stake to 35% in 2020, then bought the rest a year later, a deal that’s been a home run for investors on both sides and simplified Apollo’s relationship to the source of a huge portion of its assets under management.

At the time of the acquisition, KKR said it expected to manage about $90 billion of Global Atlantic’s money. So even with a price tag that continues to grow, it’s likely worth it to lock down full ownership.

Notable

- “Investors have long fretted about Apollo’s dependence” on a publicly traded Athene — WSJ

- “Permanent AUM that can grow, that generates fees and carry” — KKR executive Scott Nuttal in 2020 on the deal’s rationale