The News

Egypt was declared malaria-free by the World Health Organization, after nearly a century of work to eradicate the disease in the country.

Egypt saw 3 million cases a year in the 1940s, and the Aswan Dam’s development in the 1960s created new bodies of standing water for the mosquitoes to breed in, but by 2001 the disease was “firmly under control,” according to the WHO. “The disease that plagued pharaohs now belongs to [Egypt’s] history,” the WHO’s chief said.

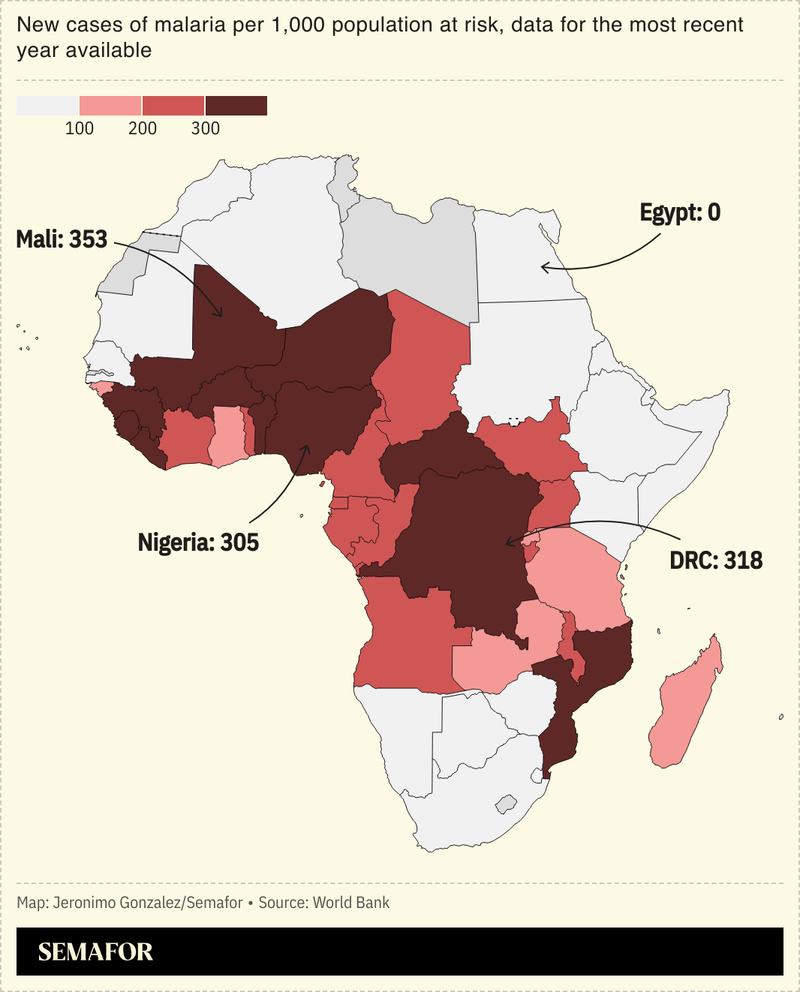

It’s the 44th country to be certified, but the wider battle against malaria goes on: The mosquito-borne disease still kills around 600,000 people a year, the large majority of them children in sub-Saharan Africa.

SIGNALS

A ‘historic’ declaration for Egypt

The WHO’s director-general described the news as “historic.” The mosquito-borne disease certainly has a long history: Boy pharaoh Tutankhamun, who lived between 1332-1323 BC, suffered from malaria, along with up to 70% of ancient Egypt’s population, a microbiology expert noted in The Conversation. Egypt secured its malaria-free certification through early case identification, vector control, public education, and “strong cross-border partnership” with neighboring countries like Sudan, the WHO said. But the battle still isn’t over, as “multisectoral efforts” spanning surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment must be tirelessly maintained, the country’s deputy prime minister cautioned.

The global disease burden has shifted

Much of the world is moving away from infectious diseases toward non-communicable diseases like diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, but low- and middle-income African countries now face a “double burden,” according to a 2022 study. Inadequate insurance systems mean people delay treatment at the onset of symptoms or resort to self-medication, which, combined with often cheaply imported substandard medications sold by the private sector, has led to the emergence of drug-resistant malaria strains, the authors wrote. There also seems to be a vicious cycle at play between poverty and malaria, where the poorest are often the most likely to be affected, and the disease itself perpetuates poverty “because the sick cannot work or go to school,” Science reported.