The News

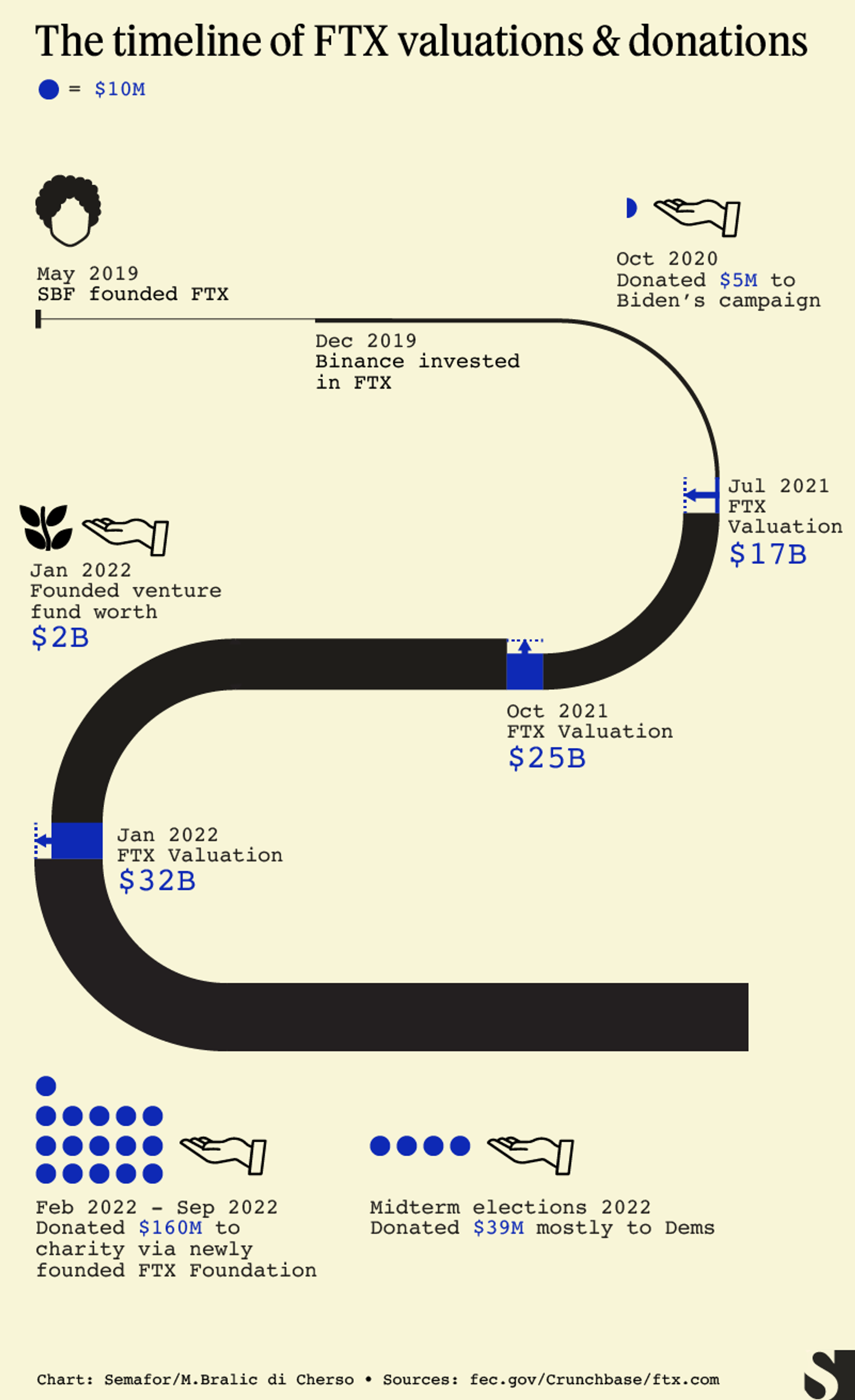

A week ago, Sam Bankman-Fried seemed like crypto’s inevitable king. He was bailing out fallen rivals and advising members of Congress. FTX was feted by major Silicon Valley investors and slapped its name on sports stadiums.

FTX, which was one of the world’s biggest crypto exchanges, is now on the brink of insolvency, trying to plug a hole that people familiar with the matter put at between $8 billion and $10 billion. It is winding down an affiliated trading arm, Alameda Research, whose website disappeared from the internet on Wednesday.

“I fucked up,” Bankman-Fried, who is an investor in Semafor, tweeted Thursday in his first public comments in days. “I should have done better.” He said he had badly miscalculated the risk in FTX’s business and was unprepared for a wave of customer withdrawals.

The unraveling began Sunday, with a shot fired on Twitter from a rival. Changpeng Zhao, the CEO of Binance, said his firm would sell its holdings of a token, called FTT, backed by Bankman-Fried’s firm. Zhao cited “recent revelations” about FTX, a nod to a story published a week earlier by CoinDesk that said Alameda was heavily invested in FTT and questioned its financial health.

Panicked investors tried to sell their tokens, and FTX didn’t have enough cash to redeem them. Bankman-Fried, a major donor to Democratic candidates, frantically scoured Wall Street and Silicon Valley billionaires for a $1 billion-plus lifeline, Semafor reported Tuesday. He ultimately agreed to sell to Binance, but even that tentative deal quickly fell apart.

Most of FTX’s legal and compliance teams, including its general counsel, quit before Binance could even roll up its sleeves. Binance backed out of the deal Wednesday, saying FTX’s “issues are beyond our control or ability to help.” Venture capital giant Sequoia wrote down its stake in FTX — which it had valued at $32 billion and just six weeks ago, in a blog post since removed from its website, predicted would eclipse JPMorgan Chase as finance’s big fish — to zero.

The seeds for the implosion were planted months ago. In June, Alameda lent $500 million to a troubled crypto firm, which soon went bankrupt. Reuters reported that Bankman-Fried transferred at least $4 billion from FTX to Alameda to cover those losses. At least some of that money belonged to FTX’s customers, who had bought FTT tokens with it, Reuters reported. That recalls the 2011 collapse of MF Global, which dipped into customer accounts to cover its own losses.

In this article:

Liz’s view

Crypto pioneers like Bankman-Fried claimed to be reinventing finance, achieving some kind of escape velocity from the system they disdained. They weren’t.

FTX fell headlong and seemingly fatally into the oldest and surest trap in finance: It borrowed short and lent long. Its depositors had the right to ask for their money back at any point by selling their tokens.

Ignore innovations like tokens and wallets; what followed was a classic run on the bank. It’s the same thing that took down Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and Washington Mutual in 2008, Long Term Capital Management in 1998, and thousands of stockbrokers in 1929. In each case, someone (trading clients, depositors, investors) had given those institutions money and those institutions had turned around and committed that money to long-term, risky, often illiquid assets.

That process is fine. It’s how the financial system works. It’s the reason it exists. Banks and brokerages and all the other middlemen turn short-term, safe things like bank deposits into long-term, risky things like mortgages or yacht loans or Italian bond swaps. They do that by taking some risk: Banks assume all of their depositors won’t ask for their money back at the same time.

The keys are managing and disclosing that risk. Banks keep a lot of their assets in cash and cash-like investments like Treasury bonds, while hedge funds and private-equity funds lock up their investors’ money for months or years at a time. FTX did neither, and the lack of disclosure across crypto firms like it make it impossible for investors to make informed decisions.

This should, and almost certainly will, light a fire under Washington regulators, which have mostly left crypto alone. A good and easy first step would be requiring all firms over a certain size to disclose their assets. Let investors know which tokens are backed by safe things like cash and Treasury bonds and which ones are vapor. The market will price in that risk and self-correct.

Room for Disagreement

Applying old-world regulations to new-world technology may kill it in its crib. In an interview with Semafor, Coinbase’s CFO, Alesia Haas, said that rules were crucial but cautioned against a copy-and-paste approach. She speaks from experience: Haas joined Coinbase after a career at OneWest, the successor to IndyMac, which was one of the largest bank failures in U.S. history when it went belly-up in 2008.

“We agree that we need to have disclosures. We agree that we need to have reporting,” she said. “But we may not need to have a physical, wet signature when you transfer a security token from party A to party B.”

“The challenge is that physical signature is enshrined in law right now,” she added. “So how do we bring those laws forward to a digital age?” (Keep reading for the full Q&A.)

Notable

- The financial system survived 2008 in large part because big players like JPMorgan, which bought Bear Stearns and WaMu in shotgun weddings, were strong enough to step in and save them. Jamie Dimon famously regrets doing so, but it worked. The problem in crypto, the bank’s analysts wrote this week, is that “the number of entities with stronger balance sheets able to rescue [weaker ones] is shrinking within the crypto ecosystem.”

One Good Text

Liz wanted to know what former SEC Chair Jay Clayton, who ran the agency from 2017 to 2020 and tried to tackle some of the excesses of the crypto craze, made of the situation.