The News

A Miami company has been making a splash in the sports business buying up financially troubled teams, like a once-great British football club that hasn’t won a league title in 36 years.

As its lineup grew — a German soccer club, a British basketball team — few in the sports world or on Wall Street could figure out 777 Partners or where its money had come from.

Like a lot of the cash sloshing around private equity these days, much of 777’s money comes from an unlikely and pedestrian source: insurance. The firm owns a Bermuda-based reinsurer whose policy premiums and annuities payments appear to have bankrolled much of its buying spree.

Last week, those cozy ties between 777 Partners and its captive insurer sparked a credit-rating downgrade that may threaten its ability to fund its growing empire.

A major credit-rating agency, AM Best, downgraded the insurer, 777 Re., because of its “weak” balance sheet and lack of up-to-date financial statements. It cited the fact that the insurer is heavily invested in deals ginned up by its parent company, 777 Partners, and said it was troubled by “governance and risk management practices that led to the significant investment in affiliated assets” that the company has now promised to sell.

777 declined to comment. A person close to the company said the downgrade isn’t “material” and that most of the company’s insurance money will be invested in third-party deals, not 777-affiliated ones.

Questions have been swirling for weeks about the source of 777’s money, and intensified after the New York Times reported last month that the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority had raised concerns about its lack of audited financial reports.

It’s not clear exactly what the insurer owns — in other words, what it has done with the $3 billion in customers’ money it holds. Bermuda requires fewer disclosures than U.S. regulators.

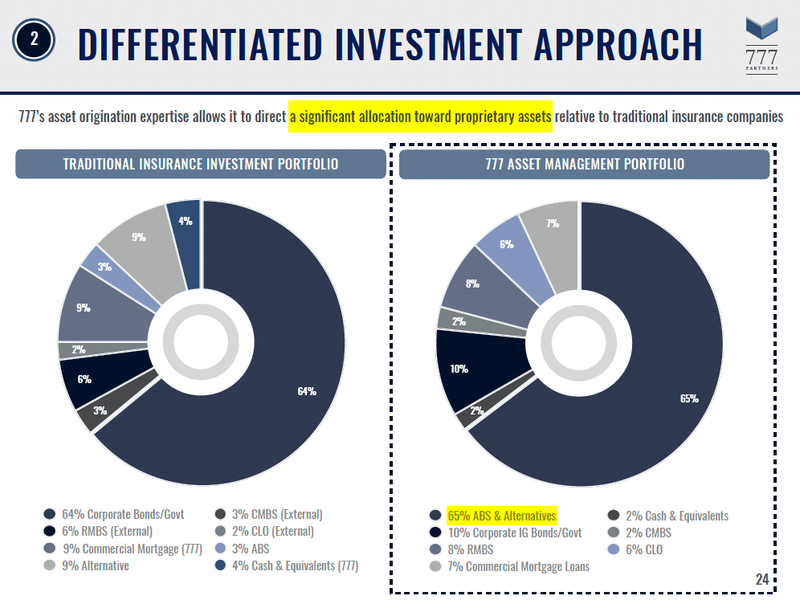

But a 2021 pitch to investors lays out what the firm’s co-founders, Josh Wander and Steven Pasko, believed was their secret sauce. They explained that 65% of the policyholders’ money would be invested in riskier things like private-equity funds and asset-backed securities, compared to 12% at traditional insurers, according to an investor presentation viewed by Semafor. “Proprietary assets” would replace deals sourced from other money managers, and insurance premiums would flow straight to companies owned by 777 as loans, the presentation showed.

The pitch promised returns of 40%, more than twice the average private-equity fund and four times what banks produce. It hoped to raise as much as $500 million to pay off debt, according to the presentation, but appears to have raised half that.

Pristine credit ratings are crucial for insurers, reassuring policyholders that the company will be around to pay out. The downgrade will make it harder and more expensive for 777 to raise money, squeezing a company that has already racked up a string of unpaid bills and owns a growing stable of sports teams with huge debts of their own.

In this article:

Step Back

Insurance premiums have become the new bank deposits, a seemingly limitless pot of money that private-equity firms can use to fund their deals. Apollo’s huge profits from Athene sparked a land rush among its competitors, which have been snapping up insurers of their own. Regulators are watching them closely, egged on by traditional competitors like MetLife that claim these new owners have an unfair advantage.

Liz’s view

Finance is about incentives, and private equity’s new obsession with insurance has some troubling ones.

Academic research shows that the new owners quickly shift their policyholders’ cash from safer investments like municipal bonds into riskier and, ideally, more profitable ones like bundled mortgages or aircraft leases. State regulators keep a pretty close eye on U.S. insurers, and there are limits to how risky their holdings can be.

But there’s a more pernicious incentive, too, one that appears to have played out at 777. At the same time private-equity firms have been buying up insurers, they’ve also been getting into the lending business, stepping in where skittish banks have pulled back.

It’s one thing for a private-equity firm to decide that its captive insurers should own more mortgage bonds. It’s another when those mortgage bonds were assembled by the private-equity firm, which needs to move them off its books. Swap mortgage bonds for troubled sports teams — Everton alone lost £166 million over the past two seasons — and it’s not hard to see why people have questions about 777’s finances.

Room for Disagreement

Sports assets have been only going up in value. “Teams were once considered poor, unpredictable investments,” The Ringer’s Dan Moore wrote last year. Today they’re among the most coveted assets in the world.” And because the market for sports teams is increasingly global (see: the influx of Middle Eastern money) there will likely always be an exit.

Notable

- Private equity-owned insurers get higher returns, but “there is no evidence that this is a consequence of general partners’ skill.”