The Scoop

New details show that the obscure Miami firm snapping up global sports teams used a $1.5 billion pot of customers’ cash at an insurance company it controls to do so.

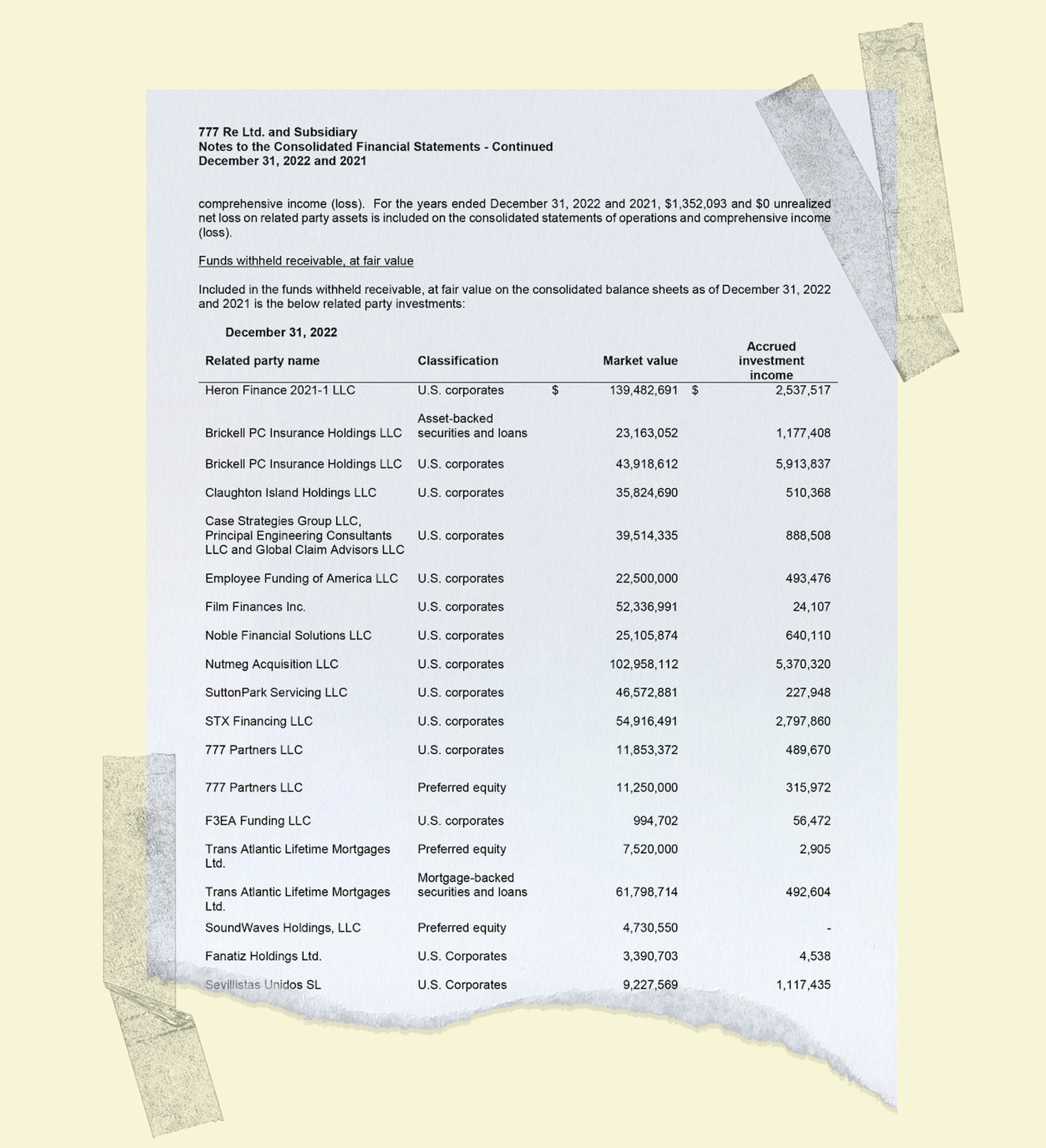

Financial documents reviewed by Semafor reveal that 777 Partners used policyholders’ money to buy European soccer clubs, invest in a South American streamer, launch a payday lender and a budget Canadian airline, and make dozens of other riskier bets.

777 came seemingly out of nowhere this year to bid for Everton, one of the oldest soccer teams in England. Few in the sports world or on Wall Street knew where it got its money. The documents show that much of it came from U.S. customers of its captive insurer, 777 Re., who hold life policies or annuities with the firm.

In all, half of 777 Re.‘s $3 billion in customer funds — which it is supposed to invest conservatively enough to ensure it can pay future claims — went into riskier deals that 777 Partners had created, the documents show. That includes $112 million invested into entities that 777 Partners used to buy Italian, French and Spanish soccer teams.

“This is a mischaracterization of our assets, as roughly half of the exposure as of year-end 2022 that you describe, which is treated under US GAAP as related party exposure, bears no credit exposure whatsoever to 777 Partners or its affiliates,” a spokesperson for 777 said in a statement. “For example, roughly 500mm invested in third-party bankruptcy remote structured settlement securitizations where the underlying credit risk is to large U.S. insurance company annuities, i.e. Prudential, Metropolitan and AIG.”

Semafor reported Tuesday that 777 Re. had been downgraded by a credit-rating agency unnerved by its investments, a major blow for any insurer. The new documents show exactly where its customers’ money went.

Life insurers collect premiums up front but only pay out decades later, making them tantalizing vehicles for private investors. But traditional insurers tend to invest conservatively in stocks and bonds.

In a presentation to investors in 2021, 777 Partners said it planned to buck that conventional wisdom. Two-thirds of customers’ money would go into risky things like bundled loans, real estate, and private equity, and it would focus on “proprietary” investments that 777 Partners itself created.

The ratings agency, AM Best, said in its downgrade report that the company had agreed to sell some of those related-party investments.

Here’s a sampling, according to the documents:

- Fanatiz, a South American soccer-streaming platform backed by 777 Partners.

- A payday lender whose corporate filings in Florida are signed by Mollie Wander, 777 Partners’ co-founder Josh Wander’s sister and a senior lawyer at the firm.

- A company controlled by 777 Partners that leases aircraft to budget airlines also controlled by 777 Partners, and a separate shell company that lent money to help purchase the Boeing 737 Max planes.

- $22 million invested into 777 Partners itself.

In this article:

Liz’s view

I wrote yesterday about the incentives that kick in when Wall Street’s financial engineers take over insurers, which is happening more and more.

Academic research has shown that the new owners shift policyholders’ cash from safer investments like government bonds into riskier ones like real estate. Around the margins, that’s understandable and maybe even healthy. Stodgy insurers that never warmed to private markets are probably sacrificing returns. But:

There’s a more pernicious incentive, too, one that appears to have played out at 777. At the same time private-equity firms have been buying up insurers, they’ve also been getting into the lending business themselves. …

It’s one thing for a private-equity firm to decide that its captive insurers should own more mortgage bonds. It’s another when those mortgage bonds were assembled by the private-equity firm, which needs to move them off its books and collect its fee.

To 777 Partners, this dynamic is a feature, not a bug. In the investor presentation, Wander and co-founder Steven Pasko said their insurance business would generate huge returns by putting most of its money into high-risk, high-return “proprietary” investments — exactly the kind of cozy and less-liquid dealings the documents show. They said the quiet part out loud.

The result: an insurance company whose holdings would make a hedge-fund manager blush, and policyholders whose fortunes are now tied to a French soccer team relegated to the country’s third-tier league.

Room for Disagreement

One of the most successful and admired investors in the world does this all the time and it works out fine. Warren Buffett’s insurance companies, including GEICO and Berkshire Hathaway Re, collect premiums that he uses to buy operating businesses like Dairy Queen and BNSF railroad.

Called “float,” it’s a unique feature of the insurance industry that “allows us to enjoy the use of free money — and, better yet, get paid for holding it,” Buffett wrote in a 2010 letter to shareholders. But he added: “Outstanding economics exist at Berkshire only because we have some outstanding managers running some unusual businesses.”

Notable

- The New York Times reported last month that the U.K.‘s Financial Conduct Authority had raised concerns about 777 Partners’ lack of audited financial reports.