The Scoop

777 Partners, the sports investor whose finances are now under intense global scrutiny, has had a silent partner for years: the chief executive of a U.S. insurance company, whose customers have unwittingly funded 777’s rapid expansion through a web of previously unreported transactions.

Kenneth King, who runs a network of insurance and investment firms, has steered hundreds of millions of dollars for years to 777, whose bid for one of England’s oldest soccer teams has raised questions both among sports executives and regulators about where, exactly, its money comes from.

King’s firm, A-CAP, sold customers’ insurance policies to 777’s reinsurance arm, separately loaned at least $400 million to 777 Partners itself and various portfolio companies, and sits on the committee that oversees its investments, according to people familiar with the matter, and internal and public documents.

One loan last year from an A-CAP insurer to 777 was quickly re-lent to a Miami shell company controlled by King to buy an $11 million beachfront condo, documents show. Other loans have helped 777 meet last-minute deadlines to fund its portfolio companies, and at least one covered payroll for 777 itself, people familiar with the transactions said.

Insurers have an obligation to their policyholders to safeguard their money, investing conservatively enough to ensure they can pay claims in the future. A-CAP’s involvement with 777 has tied its customers’ retirements to a payday lender, a Canadian budget airline, and European sports teams, among a grab bag of esoteric holdings.

A-CAP is controlled by King, who is also its chairman and CEO. The New York-based firm owns at least five insurance companies operating in several states including Nebraska and Utah.

In addition to providing financial firepower for 777’s dealmaking, King has also weighed in on how that money is spent, some of the people said. He sits on 777’s steering committee, and portfolio company executives told Semafor their business plans and requests for cash often went to King for review.

The New York Times previously reported some of A-CAP’s dealings with 777, including loans to Everton as the takeover process drags on. New documents show how enmeshed the two firms have been since at least 2019, just after 777 began its global sports buying spree, and how King appeared to benefit personally from the relationship.

“A-Cap is one of a number of lenders to 777 and its portfolio companies,” a 777 spokesman said. “As is standard practice in the industry, 777 is bound by confidentiality regarding the specifics of its loan activity.”

A-CAP and King did not respond to requests for comment.

In this article:

Know More

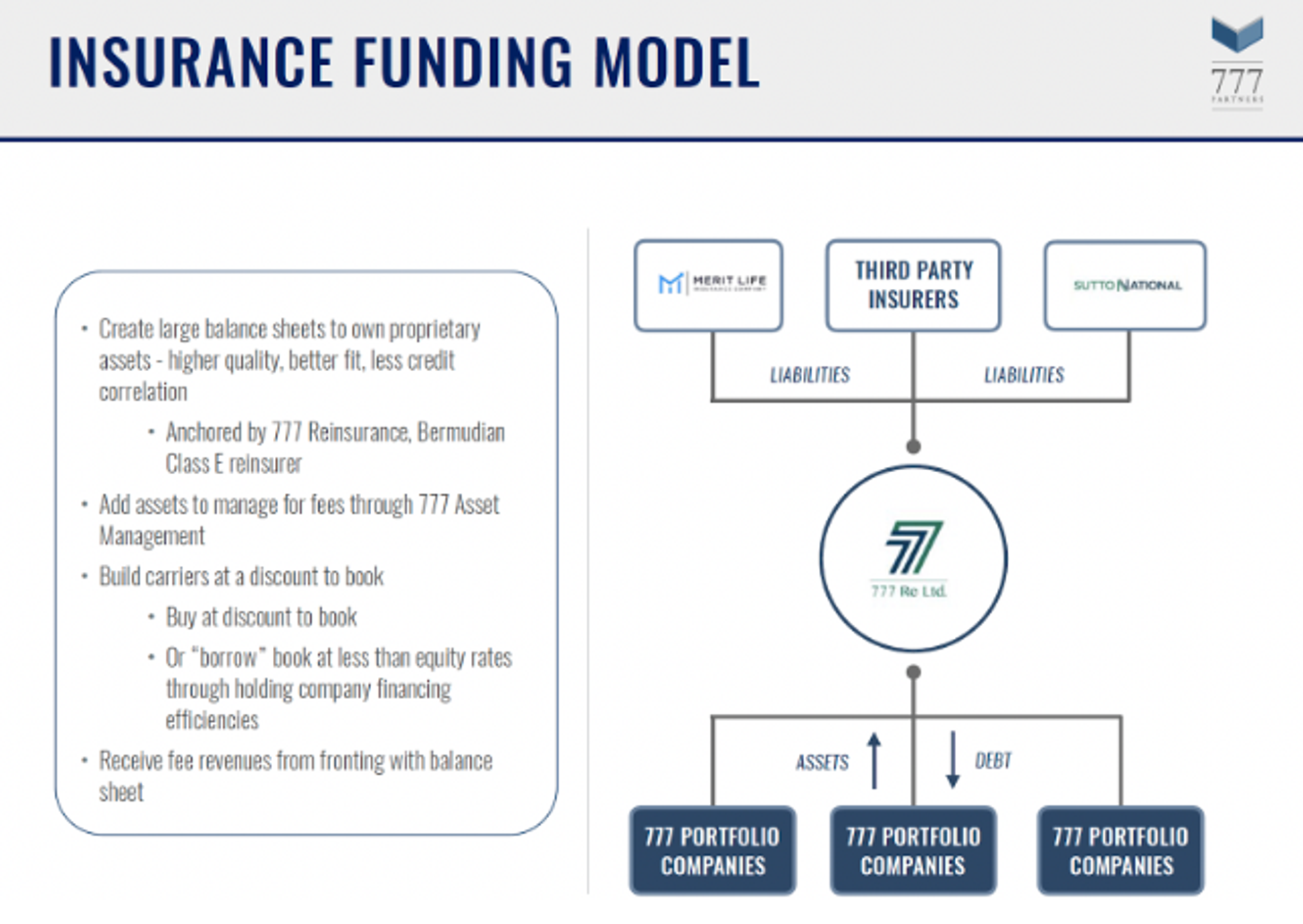

Reinsurers don’t sell insurance policies themselves, but rather buy them from insurers looking to offload risk. So relationships with primary insurers like A-CAP are key to reinsurers like 777 Re., which agree to pay out claims in the future and often take control of customers’ cash in the meantime.

That was 777’s pitch to investors. That cash — premiums for life insurance or annuities — would be invested into deals that 777 sourced and charged fees on, according to a 2021 fundraising presentation viewed by Semafor.

In 2019, an insurance company owned by A-CAP offloaded $310 million of policyholders’ cash under such an agreement to 777 Re., according to a state filing. In 2020, another A-CAP insurance arm ceded an unspecified amount of additional money.

Separately, A-CAP was quickly becoming one of 777’s biggest lenders. By 2021, the balance hit $400 million, making A-CAP its second-largest lender, according to an internal document viewed by Semafor. If 777 defaulted, A-CAP could seize “all asset[s]” not pledged elsewhere.

One loan in particular has been whispered about inside 777.

Last November, A-CAP lent about $14 million to 777 Partners, according to people familiar with the transaction. About $4 million went to cover that week’s payroll and $1 million was sent back to A-CAP, the people said, leaving $9 million.

The next day, 777 lent $9 million to a shell company to purchase a waterfront condo in Miami. The buyer, according to mortgage documents, was King.

Liz’s view

It’s time to stop calling 777 a “mystery investor” as we, the Times, and others have been doing. I still have a lot of questions, but the basic mechanics here are becoming clearer as I keep reporting.

A trove of documents and people close to the companies show that this is asset management on steroids: raising money from unusual places (with a huge reliance on one or two off-the-beaten-path sources, like King’s company) and investing it in equally unusual places (B-league sports teams, a budget airline that is “battling to survive,” a payday lender).

That half of those investments were created by the 777 itself raises eyebrows. It certainly tests the prudential limits of related-party dealings. But it isn’t all that confusing. It’s a lot easier, not to mention more profitable, to have a thing you own invest in another thing you own, especially if you’re charging management fees on one or both ends.