The Scene

Nobody wants U.S. Treasury bonds.

Once a symbol of America’s economic might and accepted as a global coin of the realm, they have fallen badly out of favor, with serious consequences for taxpayers, investors, and financial markets.

Elementary economic forces — too much supply and not enough demand — have collided to create the worst stretch for U.S. government bonds since the Civil War. The government keeps borrowing to cover its budget deficits, while once-reliable buyers of that debt, both at home and abroad, have pulled back.

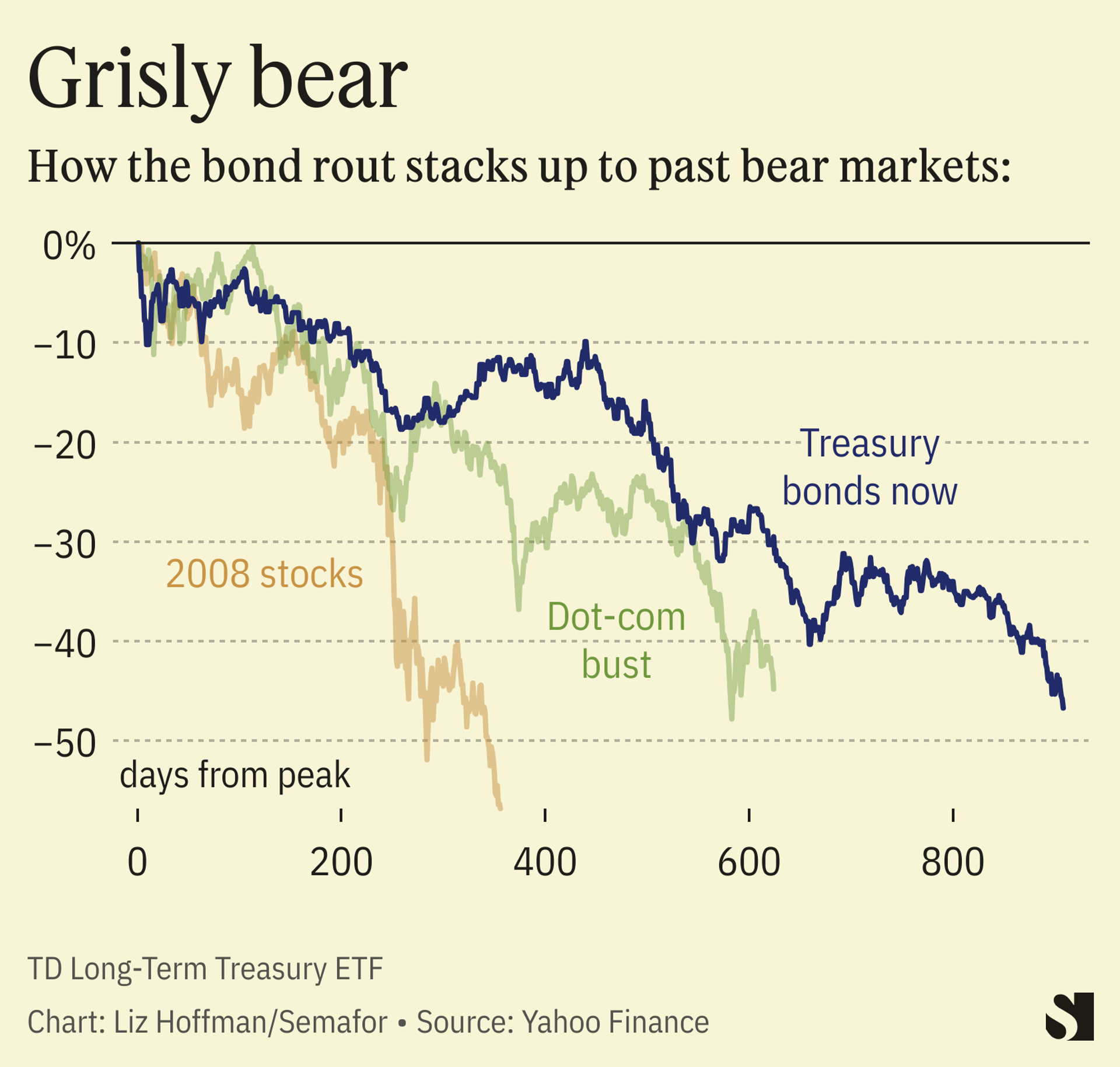

The result: Investors are demanding the steepest yields since 2007. Auctions of fresh bonds that were once routine are now going terribly. And bond portfolios are getting absolutely hammered. The longest-dated Treasury bonds are in a bear market worse than the dot-com bust and almost as bad as 2008.

The government is borrowing more than expected, increasing the supply of Treasurys and dinging their value. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve is selling down its own holdings, dumping yet more bonds into a market that doesn’t really want them.

“There’s just a lot less demand than there was even six months ago,” Goldman Sachs’ Jim Esposito said last week. “You can buy a 6-month T-bill that’s yielding north of 5%. Why wouldn’t you buy that instead of a long bond that’s yielding 4¾?”

Already 2.5% of the U.S.’s economic output is going to service its existing debts, a number that some analysts expect to hit 4% by 2030. Already running huge deficits, the only way for Treasury to pay the interest — along with ambitious spending programs like the CHIPS Act and student-loan forgiveness — is to keep borrowing.

But from whom?

China and Japan, once reliable buyers of Treasury bonds, have been selling them to prop up their weakening currencies. A decade ago they held more than 22% of U.S. government bonds; today it’s 7%.

The Ukraine war has dampened demand among Eastern European buyers, said Steve Ricchiuto, the chief U.S. economist at Mizuho. Increasing U.S. oil production means fewer petrodollars in the Middle East to be reinvested through the Treasury market.

U.S. banks, too, are stepping back.

During the pandemic, they parked a flood of new deposits in government bonds because they had nowhere else to put them. Demand for loans was light. Now that deposit glut is easing and businesses are borrowing again.

Plus, many are sitting on the same paper losses on Treasury bonds that brought down Silicon Valley Bank this spring, and are disinclined to load up on more. Bank of America, which has $132 billion of unrealized losses, has sold half its Treasury bonds this year.

In this article:

Liz’s view

A lot of investors own government bonds not so much as an investment, but as an alternate currency, a sort of Chuck-E-Cheese coin to be used inside financial markets. They were thought to be as good as cash.

But the past few years have tested government bonds, and they failed.

The market briefly broke in the fall of 2019, then again six months later in the early days of the pandemic. U.K. government bonds were behind a nearly calamitous crisis in British pension funds that forced the Bank of England to step in.

It was a $91 billion pile of U.S. government bonds that sparked Silicon Valley Bank’s failure. Big banks took the regional bank crisis as proof that not only were Treasury bonds not making them any money, they weren’t even making them safer.

The Treasury market is supposed to be the deepest and most liquid in the world, and its smooth functioning has serious consequences for other markets. For example, hedge funds that got caught on the wrong (and heavily leveraged) side of a violent Treasury swing earlier in March sold whatever else they could, contributing to the rout in stocks. Safe havens only work if they’re safe.

Room for Disagreement

Ricchiuto said there are new sources of Treasury demand that will keep the market humming. Tech companies are sitting on hoards of cash, and some experts think China’s trade surplus is as much as $300 billion bigger than the official numbers suggest.

“They’re clearly not reinvesting that in the [German] bund or [U.K.] gilt market,” he said.

He said the price swings don’t reflect a broken market, but rather a debate over whether the Fed will hit its 2% inflation target or quiet-quit closer to 3%.

Notable

- Of course there are hedge funds cleaning up on the bond rout. — Bloomberg

- U.S. tech giants sold billions in Treasury bonds as rates rose. — EuroFinance