The News

BlackRock’s $12 billion acquisition of HPS Investment Partners shows that what was once set up as an existential war between public and private lending is anything but.

BlackRock, best known for its ultra-cheap index funds, has been looking for a way into the fast-growing world of private credit, bespoke arrangements negotiated directly with corporate borrowers. HPS, which was founded in 2007 by three breakaway Goldman Sachs bankers, has $150 billion in such loans and will sit alongside BlackRock’s bond funds to “provide both public and private income solutions.”

In this article:

Liz’s view

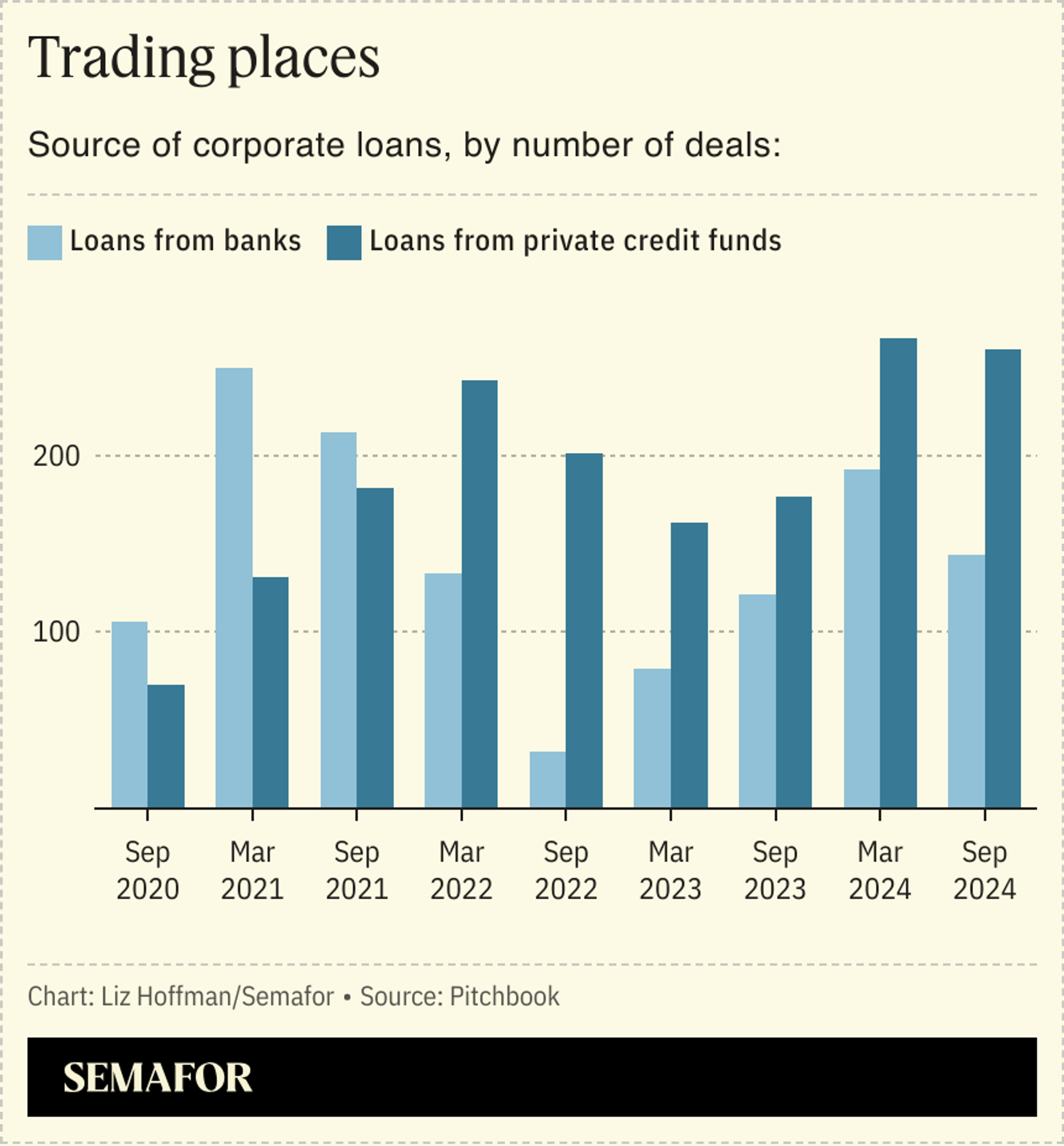

For most of its decade-long rise, private credit has been cast in opposition, and competition, to loans and bonds underwritten by banks.

That’s a satisfying but outdated lens. Borrowers want the cheapest money. Investors want the best returns. Banks want to stay just close enough to companies to solicit M&A deals while offloading risk.

As more money flows into private credit — there’s about $2 trillion now, which BlackRock sees going to $4.5 trillion by 2030 — the lines will start to blur. The same thing has happened in stocks over the past decade, with mutual funds dabbling in private rounds and buyout shops taking stakes in public companies. My guess is that in a few years, we won’t be talking about private or public credit anymore.

The winners will be firms like BlackRock and Apollo, who can come with a full menu of borrowing options. Corporate executives, too, will have more choices and competition for their business. The losers will likely be firms that believe in the bright line between public and private and are happy to stay on their side of it.

That’s why HPS, which had a hard time convincing investors on its go-it-alone IPO plans, is selling itself. It’s why even Pimco, the pure-play bond giant, has quietly added $160 billion of private credit to its $2 trillion in public debt holdings.

“There had been close to zero innovation in fixed income in 20 years,” John Zito, who oversees lending at Apollo, told me a few weeks ago. “The industry had been designed in a very narrow way: ‘Here’s a public allocation to corporate credit.’”

Apollo runs its $600 billion credit business “with no walls,” Zito said. “We come to clients with 16 or 17 different products in our bag.”

Here’s his boss, Apollo CEO Marc Rowan, speaking on a recent podcast: “Institutions historically have limited their participation in private assets to their alternatives bucket,” which accounts for about 20% of the average pension fund’s holdings. “That was done out of a mistaken belief that private was risky and public was safe — what if that basic conception is just wrong?”

Apollo, JPMorgan, and others are building out trading desks to buy and sell private loans the way brokers buy and sell bonds. The assumption is that private loans will get easier to trade, especially as they get bigger and more standardized. Meanwhile, it’s getting harder to trade large slugs of corporate bonds without affecting their prices.

“You’re going to see a lot more acceptance and there’s not going to be ‘that was private’ or ‘this is public.’ It’s just going to be ‘that was Intel,’” Zito said, referring to Apollo’s $11 billion loan to the chip company. “The world isn’t there yet, but there’s this convergence.”

I’ve been covering this long enough to remember the first nonbank loan to crack $1 billion. It was, I swear, a big deal at the time, which was 2016.

Room for Disagreement

Some private lenders are skeptical of this convergence. One I spoke to recently doubted that there is enough interest from investors to sustain a vibrant trading market. The bespoke nature of these loans is a feature, not a bug, he said, which limits how easily they can be bought and sold. “These aren’t shares of stock,” he told me.

Notable

- Rowan’s interview with Nicolai Tangen, the CEO of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, is worth listening to in its entirety. “We don’t want the bank’s client. We want the asset.” — Spotify or Apple Podcasts