The Scoop

Goldman Sachs plans to lay off as many as 4,000 employees as it struggles to meet profitability targets and retreats from its gamble on Main Street banking, people familiar with the matter said.

Managers across the firm have been asked to identify low performers for what could be a cut of up to 8% to its workforce early next year, the people said, with some cautioning that no final list has been drawn up.

Those cuts appear to be much deeper than ones taking place at other Wall Street firms like Citigroup, which is letting go of dozens of staffers amid a market downturn, and Barclays, which is laying off about 200 people, CNBC reported.

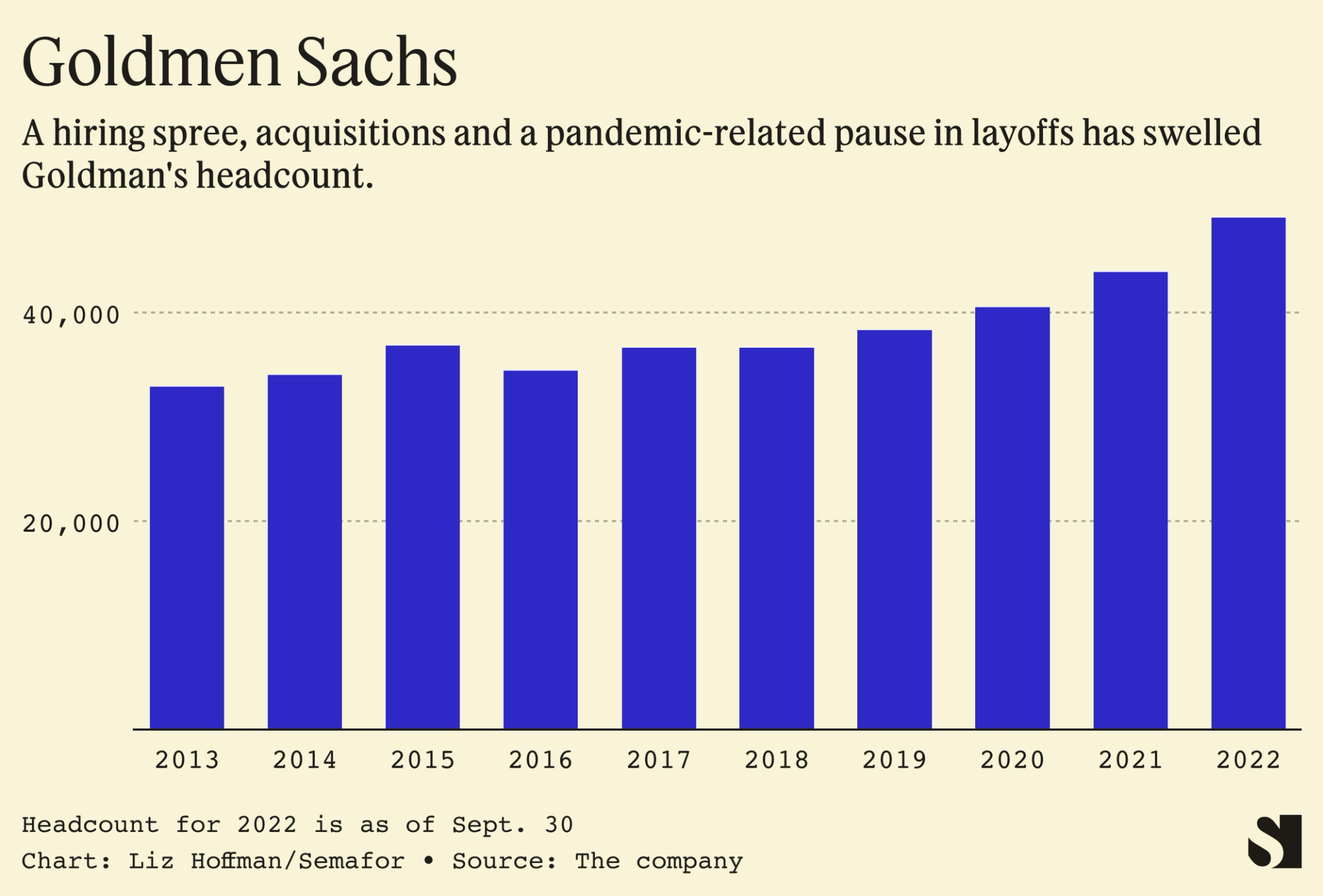

In a typical year, between 2% and 5% of Goldman’s employees are laid off or receive no bonus — “zeroed out” in industry parlance, a clear sign to start looking for another job. Like other firms on Wall Street, Goldman skipped these cullings in 2020, because the pandemic made them insensitive, and in 2021, because boomtime profits made them unnecessary.

Now, though, CEO David Solomon is falling short of a profitability goal he set in February. The dealmaking and fundraising booms have vanished, and Goldman’s big bet on consumer banking hasn’t paid off. The firm has lost billions of dollars building a tech-forward Main Street bank, called Marcus, that isn’t yet profitable.

Goldman’s workforce has swelled by a third since Solomon took over in 2018 to more than 49,000 now, largely due to a hiring spree in engineering and Marcus. Acquisitions added some, too: GreenSky, a specialty lender, had about 1,000 employees when Goldman bought it earlier this year.

In this article:

Liz’s view

Goldman’s decision to go to Main Street — a business it avoided for almost 150 years — was a sound one. There are only so many mergers you can broker, or companies you can take public, or bonds you can trade, and companies have to grow. In 2014, when Marcus was hatched at a gathering of top executives in the Hamptons, the bruises of 2008’s trading meltdown were fresh and the financial world was shifting toward safe, boring businesses like consumer banking — the one business Goldman wasn’t in.

But the firm has clearly overspent and over-hired, acting more like a tech company being cheered on by venture capitalists than a Wall Street bank bearing the scars of past crises of overexuberance. Solomon is now moving to stem those losses: The firm is dialing down new consumer loans and concentrating its efforts around partnerships, like the Apple and General Motors credit cards, where it can tap its relationships with blue-chip companies.

Dismantling that takes time, and in the meantime, the firm has a problem with shareholders. Goldman trades at 1.2 times the value of its assets, while its closest peer, Morgan Stanley, which has similar Wall Street roots but a steadier base of money management, trades at 1.6 times.

Layoffs won’t help that number this year, but will show, ahead of a planned all-day investor presentation in February, that Solomon is taking this seriously. There is only so much money to go around — and a few billion less of it, given its consumer losses– and divvying that up between employees and shareholders is an unenviable task.

Room for Disagreement

Goldman can afford to lose money on side bets because its core businesses — arranging trades, mergers, and listings — show no cracks.

It will be comfortably at the top of the global M&A and U.S. IPO rankings this year, boom-and-bust businesses that will boom again, and its traders are minting money. And while some talent might leave, it remains an employer of choice, especially with the troubles at the tech firms that lured MBA grads away.

As Institutional Investor wrote in March, that continued dominance is actually hampering investors’ enthusiasm for its pivot to Main Street. “Goldman Sachs Group struggles with a conundrum,” reporter Jonathan Kandell wrote. “Its investment bank is too damn profitable.”