The Scoop

Private investment firms are circling a major life insurer, intensifying a race for Americans’ nest eggs.

Prosperity Life, owned by Elliott Management, held sale talks this month with potential buyers including TPG and European investment firm JAB, people familiar with the matter said, though neither conversation is still live. Wall Street has been hoovering up insurance and retirement businesses, which generate cash that they can invest for decades.

Any deal would likely value Prosperity around $3 billion to $4 billion, the people said. The company manages $23 billion of policyholders’ money and has been built up through acquisitions including the July takeover of National Western Life for $1.9 billion.

TPG, JAB, and Elliott declined to comment.

In this article:

Know More

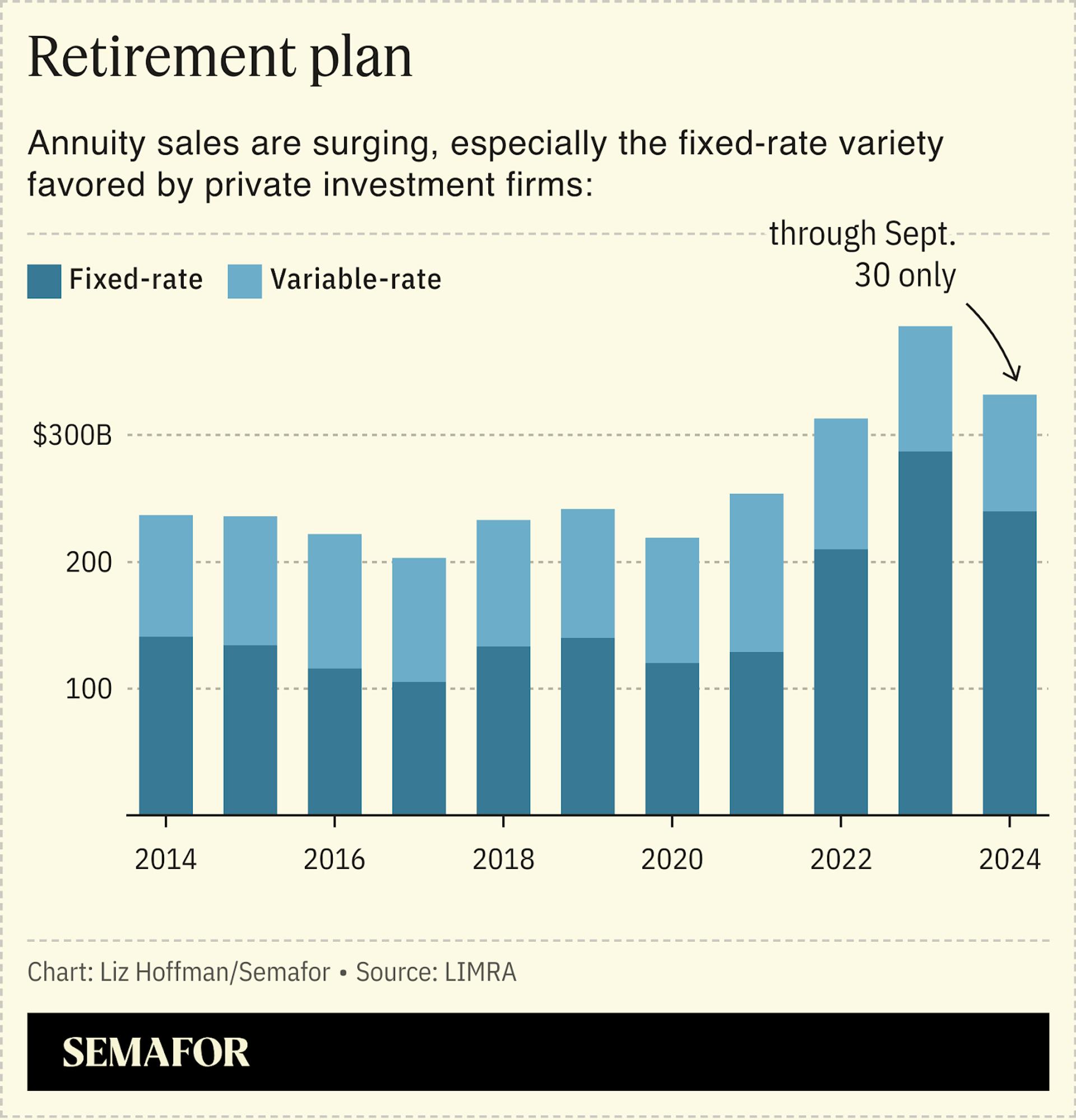

Life insurance policies and annuities — which are contracts that promise retirees a fixed income in the future — have become the hottest corner on Wall Street. The cash they generate through premiums that won’t be paid out for decades, until policyholders retire or die, are an attractive money source for dealmaking. Apollo, Blackstone, KKR, Brookfield, and other investment firms have all gotten into insurance, and rivals that don’t yet have an insurance arm are scrambling to buy one.

These firms are betting that they can invest policyholders’ money more profitably than traditional insurers, which generally favored blue-chip corporate bonds and other sleepy investments. They have, in most cases, replaced those vanilla assets with private loans, often backed by things like plane leases and consumer layaway purchases.

“I think insurance companies over the last two decades really blew it because they got out of investing,” Anant Bhalla, JAB’s chief investment officer, said at the Semafor Business Summit in June. “So who stepped in? The people are very good at it. Alternative asset managers.” (You can watch his entire interview here.)

Critics, meanwhile, warn that higher profits mean higher risks and have sounded alarms about Wall Street gambling with Americans’ retirements.

TPG, which remains on the hunt for an insurance acquisition or partner, has picked up $3.5 billion from independent insurers since acquiring a private-credit arm, Angelo Gordon, last year, CEO Jon Winkelried said at an investor conference last week.

“Not surprisingly, we’re now involved in conversations with very established large insurance companies who are coming to us saying, ‘Look, it would be interesting for us to figure out whether or not we can do business together, whether we can establish some relationship,’” he said.

Liz’s view

A CEO talking that openly about private conversations shows just how irresistible insurance money has become to Wall Street.

For decades, private equity firms found money for their deals by traveling the country and asking local and state pension funds for, say, $50 million, an expensive process that involves more suburban steakhouse dinners than Wall Street executives prefer.

Apollo’s insurance arm, Athene, brought in $28 billion last quarter by selling retirement policies, mostly through retail financial advisers. Corebridge, which has a partnership with Blackstone, brought in $20 billion.

On the other side of the investing ledger, the opportunities are growing quickly, too. Banks are pulling back from certain types of lending, opening the door for investment firms to step in. Private lending and insurance have been Wall Street’s chicken-and-egg over the past decade. Neither would be thriving without the other, which explains why TPG, having finally gotten into lending, is now looking for the insurance money to lend.

Apollo has made almost $200 billion of loans over the past year, a sizable regional banks’ worth. Much of that ends up being funded by Athene’s retirement assets. “Our target is 25% of everything and 100% of nothing,” John Zito, who oversees lending at Apollo, told me a few weeks ago.

With its long-term money — life-insurance policyholders are, of course, the last people who want their policy redeemed — this system looks safer than banks, which as we saw with Silicon Valley Bank in 2023, are vulnerable to runs. But the incentives are there for more risk-taking, with little coordinated oversight. (Insurance firms are regulated state-by-state). We have no idea how this ends.

The View From Anant Bhalla

Anant Bhalla was the CEO of American Equity, a major life insurer that was sold earlier this year to Brookfield, in a process kicked off by an unsolicited bid from Prosperity. Speaking at the Semafor Business Summit in June, he cautioned firms piling into the insurance space.

“It’s not a cheap funding trade. If you wake up and say, ‘Gosh, I wish I had insurance funding because I could now fund my [deals] at [a cost of] 4% or 5%,’ that’s not the right motivation structure. Because what are you thinking — how do I find more and more assets? How do I make more and more in fees?”

He said JAB has no plans to go public and won’t chase the fee “drug” that many investment managers have emphasized as they grew bigger, went public, and needed to show steady profits for their shareholders.

“Insurance is a good business if it’s private,” he said.