The News

Russia’s central bank unexpectedly held its benchmark interest rate firm, despite what even President Vladimir Putin acknowledged were signs of an overheating economy.

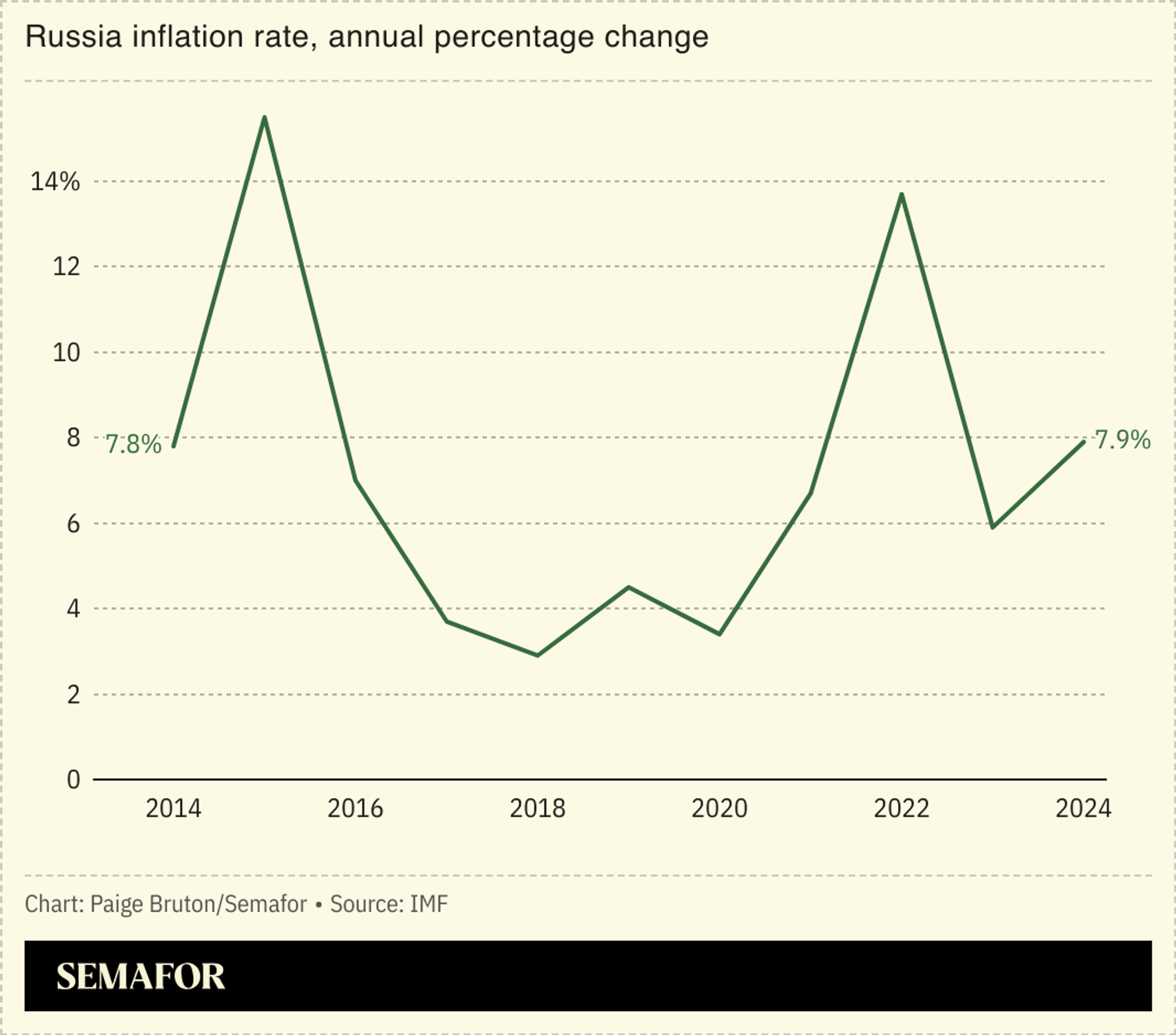

A weaker ruble has combined with labor shortages — both a result of the fallout from Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine — to drive annual inflation to 8.9%, while the IMF projects a “sharp slowdown” in economic growth.

Policymakers faced a difficult choice, though: Raising rates would have drawn the ire of major businesses and some ministers, while holding fire could risk inflaming inflation further.

“The intense pressure on the central bank... shows the stakes are unusually high,” The Bell, an outlet focused on the Russian economy, wrote.

SIGNALS

Russian elites make central bank a scapegoat

Russian business leaders have launched fierce attacks on the central bank in recent months, blaming it for hampering the economy with its eyewatering interest rates — currently at 21%. While the war in Ukraine has fueled inflation, oligarchs have focused their ire on the central bank rather than the Kremlin. The country’s biggest industrial lobby has proposed giving the government more oversight of the bank, while an influential think tank with ties to the defense ministry called for rates to be rapidly cut. The central bank, meanwhile, has stressed the importance of its independence, and has been widely credited with preventing a far worse economic collapse. But Vladimir Putin could decide to assert greater control, for example by appointing a loyalist to replace its current chair, which would only worsen Russia’s ailing economy, a former official wrote.

War economy faces growing limitations

Russia has prioritized its war in Ukraine, with military expenditure dominating the federal budget for 2025 even as pensions and welfare spending face cuts. The move has sparked frustration among the country’s pensioners, with one calling it an “outrage.” But the vast spending levels have transformed Russia’s defense industry, doubling the production of armored vehicles and ramping up ammunition output, as well as maintaining a steady stream of new recruits with massive financial benefits. Even so, much of its military production has relied on refurbishing existing stocks, which will start to dry up at the end of next year, analysts argued. And the Kremlin has already slashed benefits for wounded soldiers, and will likely have to make further cuts to military compensation as resources continue to dry up, one Russian journalist argued.