The Scene

The backlash against corporate diversity efforts became one of the year’s defining stories. But a second banking crisis never materialized. We look back at our 2024 predictions to see which ones hit the mark and which ones missed.

In this article:

What we got right

The Corporate DEI Retreat

My first story of 2024 was headlined: “Big business will be the next target of DEI attacks.” I promise that idea was revelatory enough last January to be worth printing, which shows just how quickly public sentiment has turned against corporate diversity efforts.

The backtracking started at heartland brands like Tractor Supply and John Deere, but by December had come for Walmart. The pandemic, inflation, labor shortages, regulatory crackdowns, and geopolitical tensions have kicked CEOs down Maslow’s pyramid from leisurely self-actualization to bare subsistence, and they no longer have the time, money, or credibility to spend on DEI.

Trump promised in a sprawling speech on Sunday to “stop woke” and target diversity initiatives at private companies. He has support from a growing group of MAGA money managers pitching, in one investor document seen by Semafor, “the S&P without the woke sh*t.”

Obsessed with insurance

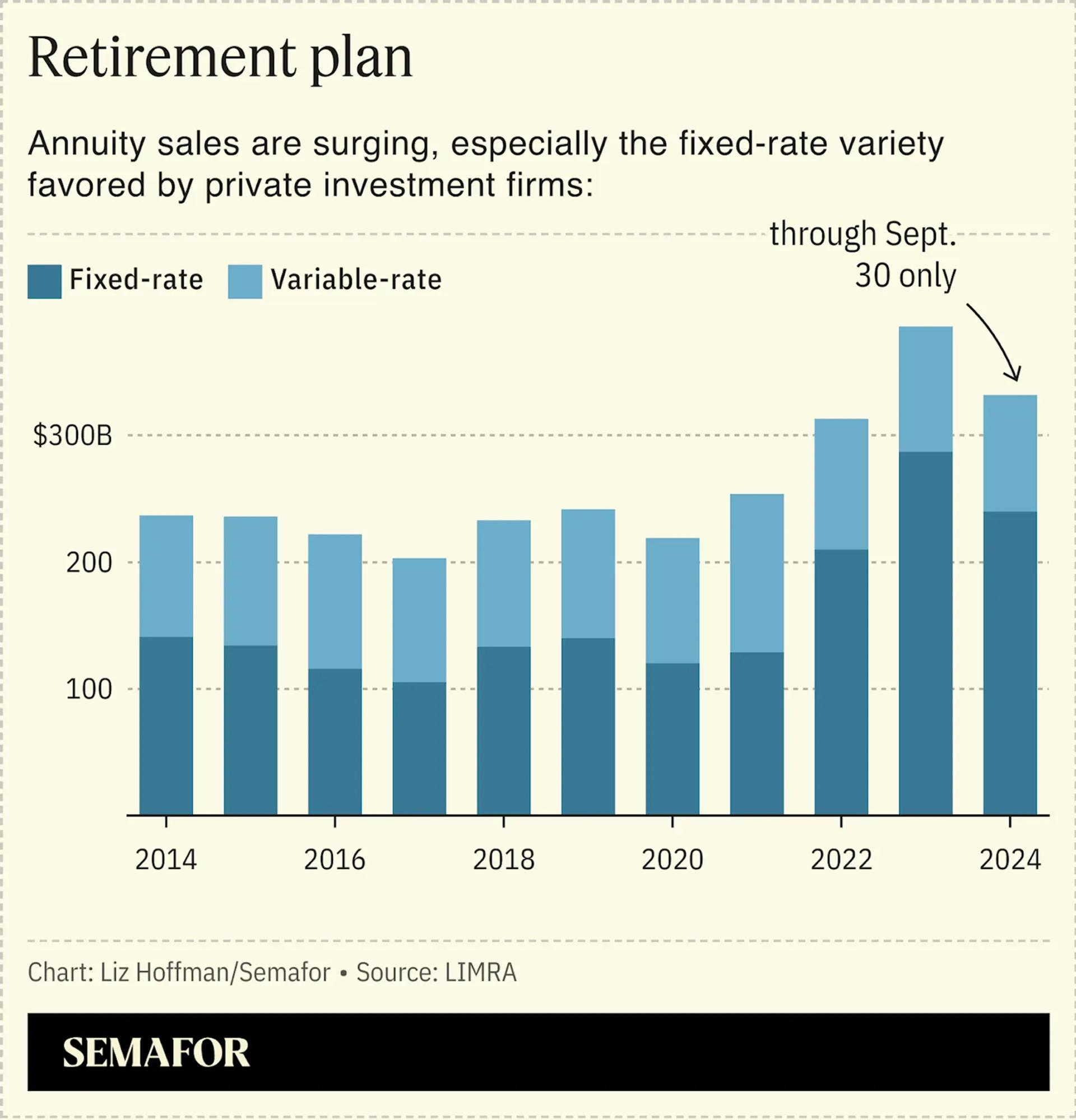

“There are two kinds of money managers these days: those with an insurance arm, and those that want one,” I wrote in May.

Wall Street sees insurance premiums and upfront cash from other products that guarantee retirement income as a cheap and plentiful way to pay for their dealmaking. Private investment firms are acquiring insurers (like Apollo and KKR have done) and striking partnerships to manage their money (the Blackstone and Blue Owl route). Insurers are beefing up their own investing prowess, but most are finding it too little, too late.

“Insurance companies over the last two decades really blew it because they got out of investing,” said Anant Bhalla, chief investment officer of JAB, which is on the hunt for an insurer to buy. “So who stepped in? The people who are very good at it.”

My last scoop of 2024 (barring any welcome tips between now and Dec. 31) was about Prosperity Life, a major insurer, drawing takeover interest. It will get sold, as will many of the independent companies on this list.

The rise of Wall Street’s one-stop shops

“Private equity retains its image as finance’s youthful rogue, but it is, generationally speaking, an old millennial,” I wrote in March, when we scooped merger talks between two giants. Specialty shops are selling out to superstores that can offer a wider range of products at lower prices.

Blue Owl grew from $165 billion to $235 billion in 2024, mostly through acquisitions. BlackRock spent heavily (at some eyebrow-raising prices) on takeovers in credit and infrastructure. General Atlantic made the first major acquisition in its 40-year history.

We haven’t yet seen a blockbuster merger, mostly because these firms have healthy egos and distinct cultures. But expect that to change as the pressure on fees continues. In selling itself to BlackRock, HPS showed that even $100 billion in client assets and a long track record of profits isn’t enough to go it alone.

What we got wrong

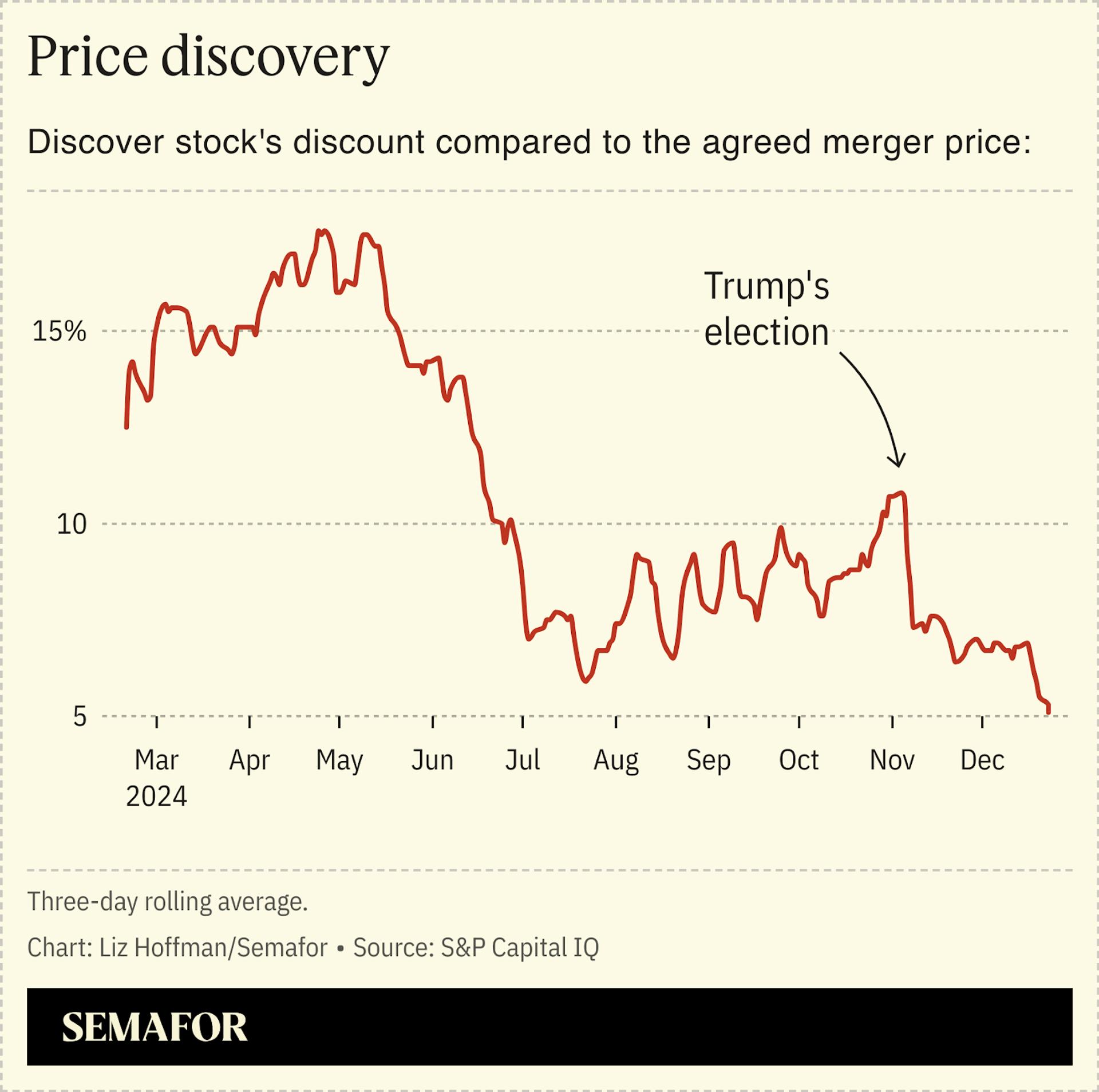

Capital One-Discover

“This deal feels like a thought experiment that escaped the lab,” I wrote in February of Capital One’s $35 billion takeover of Discover. I thought the companies were underestimating the antitrust pushback they would get, and the political dislike of credit-card companies in particular. I wrote more words than most of you probably cared to read about why Capital One-Discover won’t actually do much to break up the Visa-Mastercard monopoly.

But Trump won. Investors are now convinced the deal will get through: The gap between Discover’s share price and the agreed $183-a-share deal price has been cut in half since the election.

Bank trouble

I thought the troubles at a small New York bank this spring would be the start of a second wave of bank collapses — one that would be a more troubling omen than the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic in 2023, which were wrong-footed by a sharp and unexpected rise in interest rates.

“Banks like [New York Community] are now teetering because they misjudged their own borrowers,” I wrote. “That’s the basic job of a bank and gives this turmoil a more uneasy flavor than last time.”

Instead, NYCB’s problems were a one-off related to a 2019 change in New York City rent-control laws. Former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin put up $1 billion to rescue the bank and that was basically the end of it. Midsized banks are nearly back to their 2022 profit levels.

“I always thought the concerns about regional banks were overblown,” Sheila Bair, who ran the FDIC during the 2008 crisis, told me this week. “Hand it to the examiners. They took SVB’s failure as a wakeup call. They really got on the banks with big market loss exposures to raise capital, build reserves, and reduce positions. If they hadn’t taken such prompt action, there would have been more failures.”

A star trader’s downfall

“Lying to counterparties is a celebrated tradition on Wall Street trading floors, and efforts to put people in jail for it have mostly failed,” I wrote in July as Bill Hwang went on trial for misleading banks about his firm, Archegos, before it failed in 2021.

My view was that big banks make for unsympathetic victims and particularly these banks, which overlooked obvious red flags in pursuit of fees. But a jury disagreed, and Hwang was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Overall, it was a tough year for white-collar criminals. Sam Bankman-Fried was sentenced to 25 years for defrauding customers who were largely made whole later, lending some credibility to his argument that FTX was solvent all along, if not as liquid as one would hope. And Carlos Watson got 10 years for duping investors in his feel-good media company, Ozy.

Semafor’s Editor-in-Chief Ben Smith, who broke the Ozy story in 2021, summed up his thoughts on last week’s episode of Semafor’s Mixed Signals podcast. “The people who are legally the victims in court here are ultra, ultra rich people who really should have known better. The question of ‘how dire was this crime?’ is a reasonable one to ask.”

Mixed record

One fascinating story of 2024 was Bill Ackman’s turn as a conservative online star, and whether it would reboot his investment fortunes. Our record on this one was mixed.

In January, as his X posts criticizing Harvard’s president, campus Gaza protests, and the diversity movement more broadly got sharper, I thought it would end badly. Ackman’s savior complex has foiled otherwise sound investment ideas before, and this crusade had the hallmarks of past losses.

By the spring, a piece of evidence had changed my mind. Shares of Ackman’s Amsterdam-listed fund had soared, backed by a sea of retail fanboys and a key Israeli investor, and he was planning a IPO of his US fund, Pershing Square, to ride the wave. “Imagine what [those views] would be worth to madding crowds in America,” I wrote in May.

But the institutional investors needed to anchor a $10 billion US listing weren’t as charmed as Ackman’s 1.5 million X followers. My prediction for 2025: He’ll be back, with lower ambitions and a more solid grasp of IPO book-building.