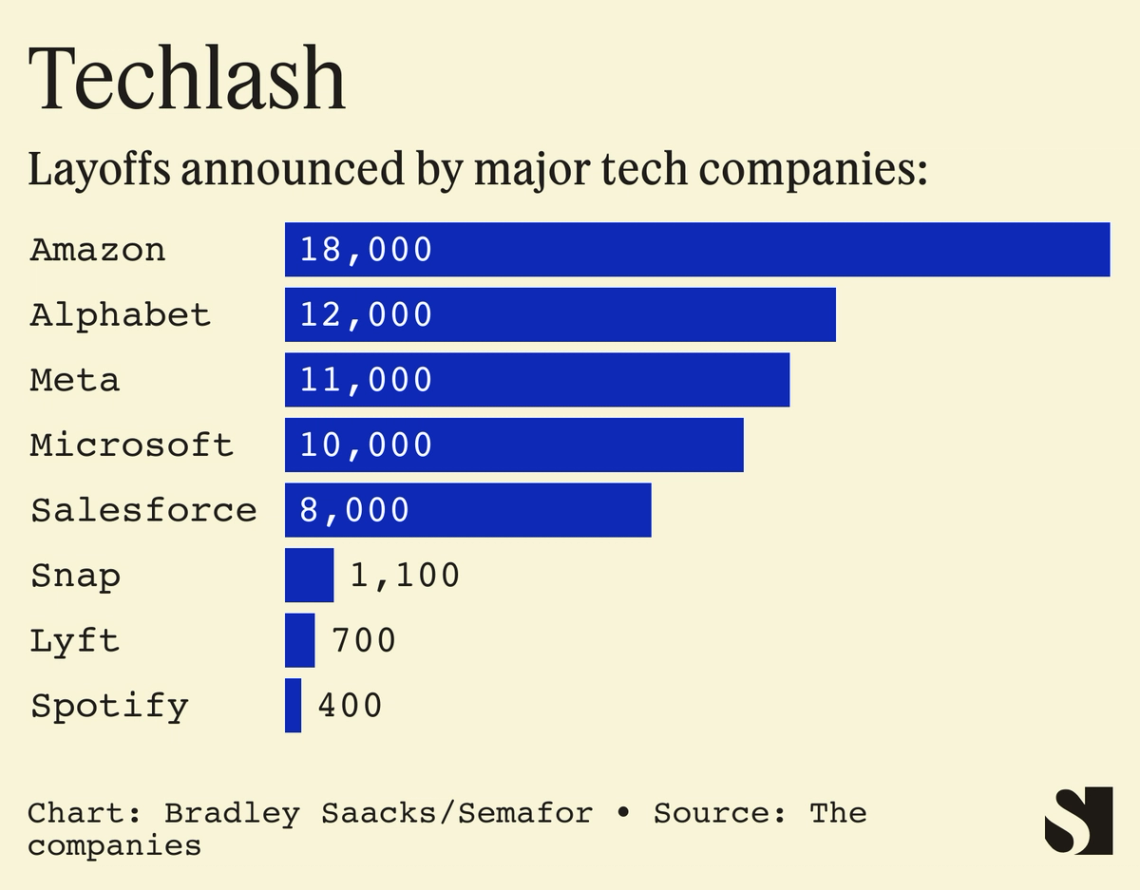

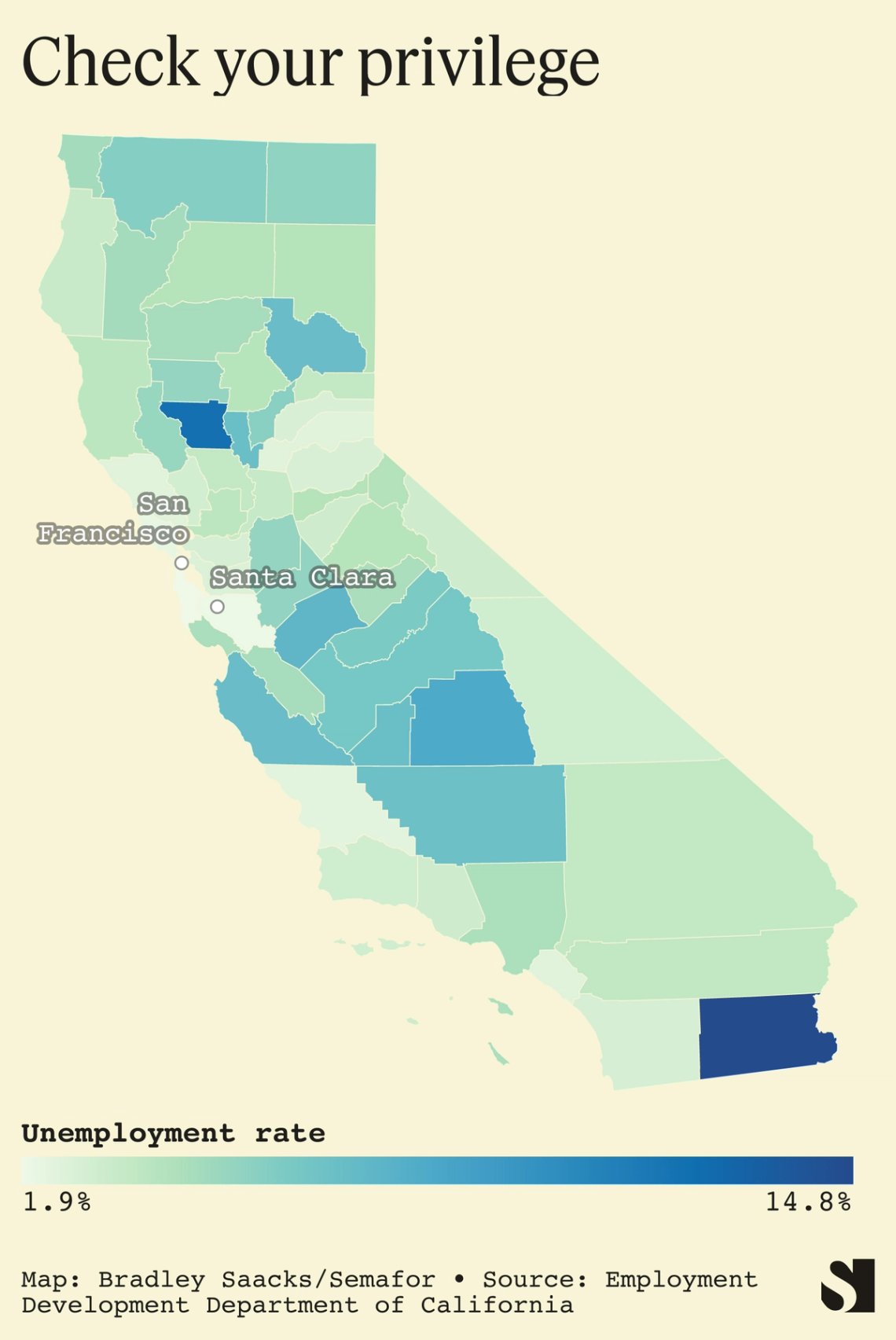

THE NEWS Silicon Valley spent the past half-decade out of reach of activist investors. No longer. Elliott Management has a multibillion-dollar stake in $156 billion Salesforce, joining fellow activist hedge fund Starboard, which has been there since the fall. Chris Hohn’s TCI has been rattling the cage at Google parent Alphabet, pushing for 37,000 job cuts on top of the 12,000 the company has already announced. Altimeter Capital wants Meta to stop pouring money into its virtual-reality headsets. And Nelson Peltz, whose firm, Trian, owns about $1 billion of Disney stock, wants a seat on its board. (Though not a Silicon Valley company, Disney has traded like one since its big bet on streaming charmed Wall Street, then fizzled.) The particulars of each campaign vary, but they’ve put four titans of California’s corporate class — Marc Benioff, Sundar Pichai, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bob Iger — under pressure. The unifying message is that these companies should trim workers and the lavish perks they enjoyed for a decade, and get back to doing whatever it is they do well. “Time to get fit,” begins Altimeter’s open letter to Zuckerberg.  Mike Blake/Reuters Mike Blake/ReutersLIZ’S VIEW Tech giants are no longer untouchable. It’s not just that their stocks are cheap enough to tempt activists, but rather that they’ve lost the armor that once protected them: investors’ unbridled FOMO. Activists are mostly what Wall Street calls “value” investors. They sift through thousands of listed stocks to find the ones that should trade higher, then push them to do things — spin off underperforming divisions, replace their CEOs, sell their real estate — that might close the gap. But for the past half-decade or so, tech stocks have been the opposite of a value play. They’ve traded well above the sum of their parts, or any historically rational multiple of their earnings, and flourished despite obvious flaws in their governance and strategies. No matter that Salesforce lost two co-CEOs in three years, or that Zuckerberg alienated needed allies in Washington. The louder old-school investors shouted that a bubble was forming, and that short-sighted investors were cheering on unsustainable growth, the higher their stocks went. Low interest rates pushed investors into riskier bets. The higher tech shares went, the more emboldened their leaders became to keep spending — on streaming, on the metaverse, on hacking the human lifespan. “Like many other companies in a zero rate world,” Altimeter wrote, “Meta has drifted into the land of excess — too many people, too many ideas, too little urgency.” Companies might howl (Disney has thrown up a particularly robust stiff-arm) but I suspect some CEOs might privately welcome the outside pressure. It makes it easier for them to take on workforces that, already pampered by free massages and a steady stream of headhunter calls, were only further emboldened by the pandemic. Tech companies had a hard time getting their workers back to the office, and the tug-of-war showed just how much power sat with employees who are now facing management — and shareholders — who think they’re overpaid at best and superfluous at worst. It all has a very early-2010s vibe to it. In 2013, ValueAct got a board seat at Microsoft. A year later, Apple boosted its stock buyback program after a pair of activists, Carl Icahn and David Einhorn, urged it to do so. The first half of that decade was perhaps the heyday of large-cap activism, with Mondelez (market value at the time of $76 billion), Procter & Gamble ($177 billion), and Apache ($38 billion) all facing down restless shareholders. Since then, bets have been smaller and campaigns less headline-grabbing.  ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT The companies now in activists’ sights still have plenty of defenses. For starters, they’re still expensive. Even after 2022’s slide, the Nasdaq 100 index still trades at 24 times the expected next-year earnings of the big tech stocks that make it up, well above its average over the past decade. And some, like Meta, remain controlled by their founders. Other CEOs like Benioff and Iger don’t hold sway over their companies and investors through big stakes, but rather force of personality. It’s not time to call the top on the cult of the founder just yet. NOTABLE - A few years ago, Alphabet reorganized itself, shining a light on the stuff that makes money (search and YouTube) and putting its moonshots into an “Other Bets” category. The Information dives into that bucket, which includes self-driving cars and robotics, and the pressure the company is under to rein in spending there.

|