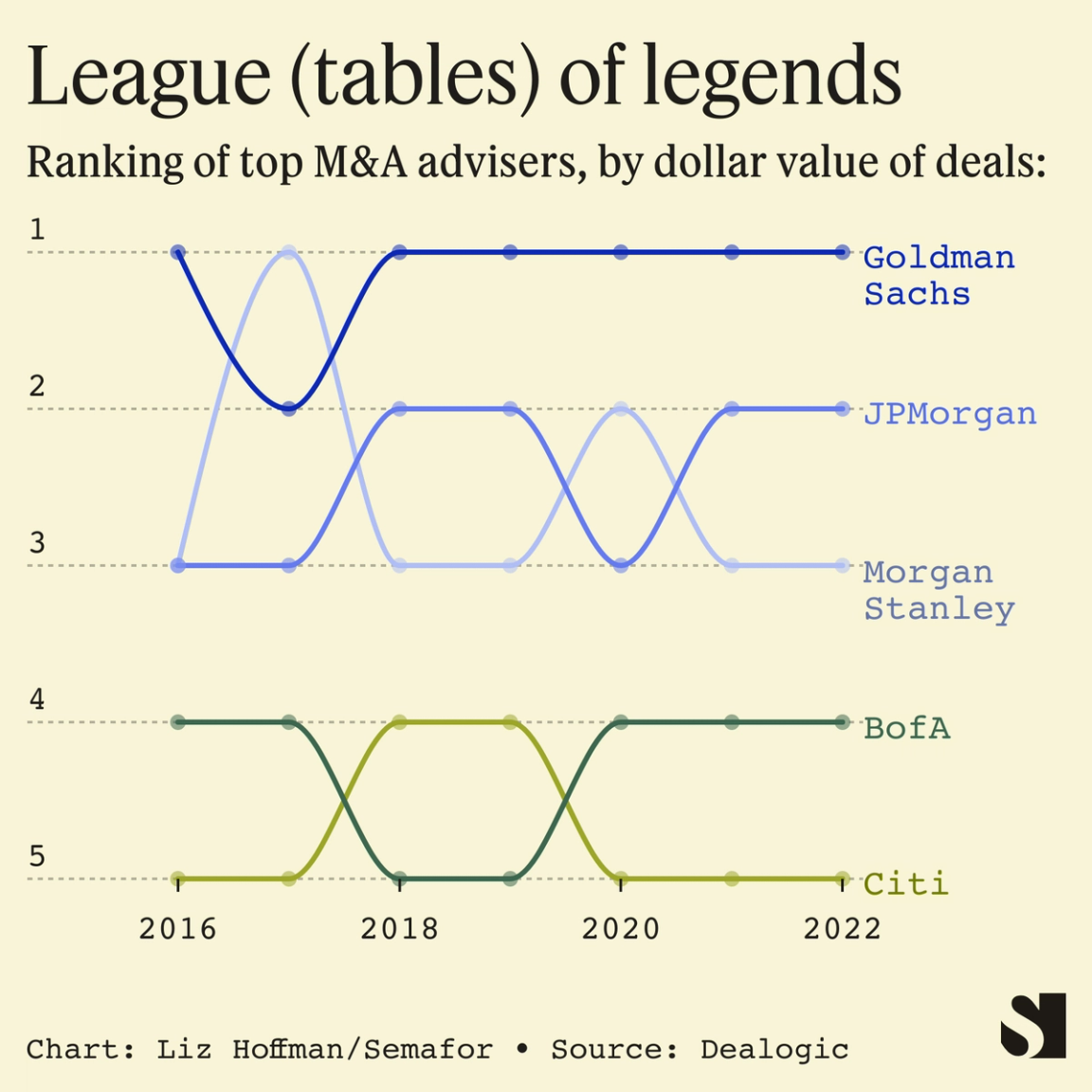

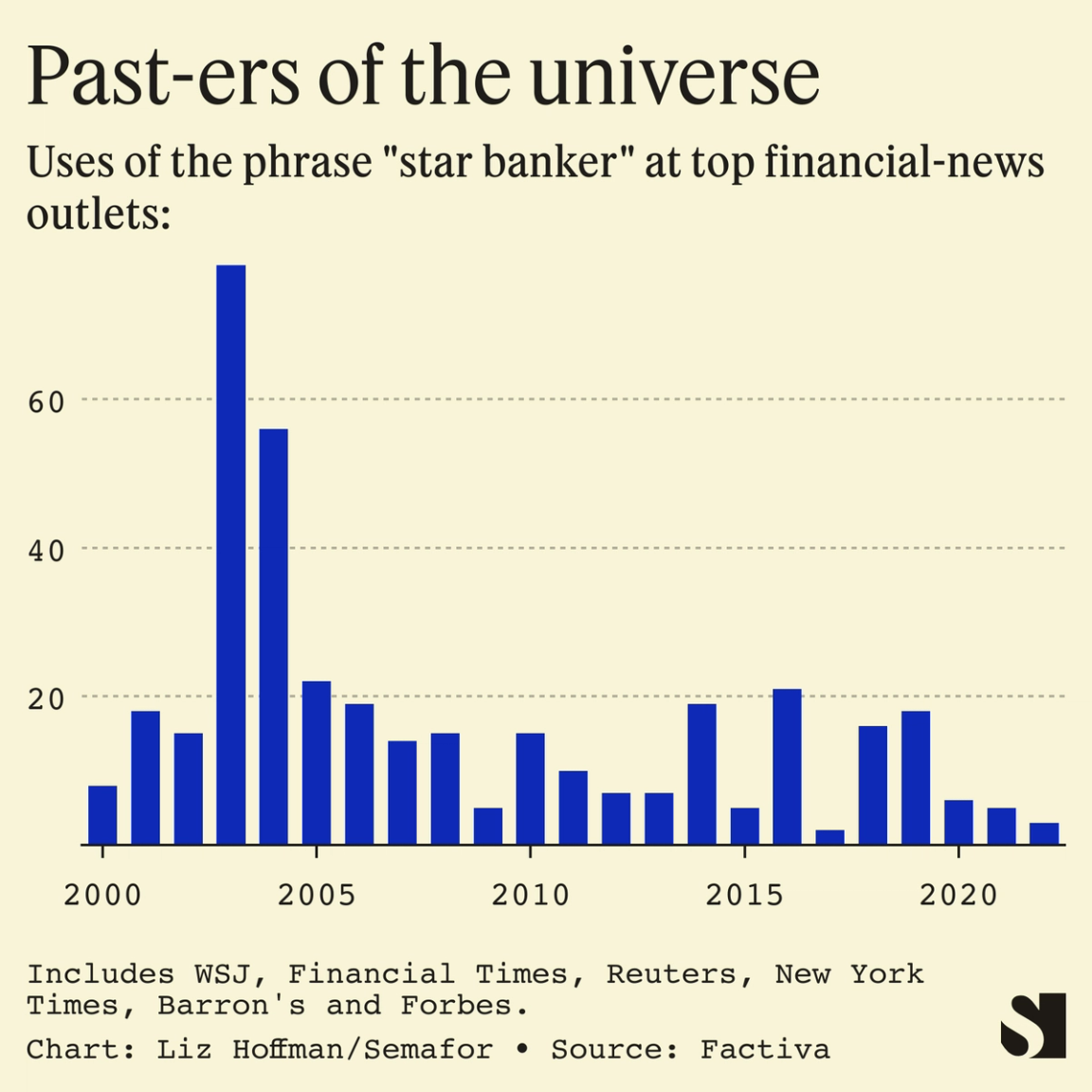

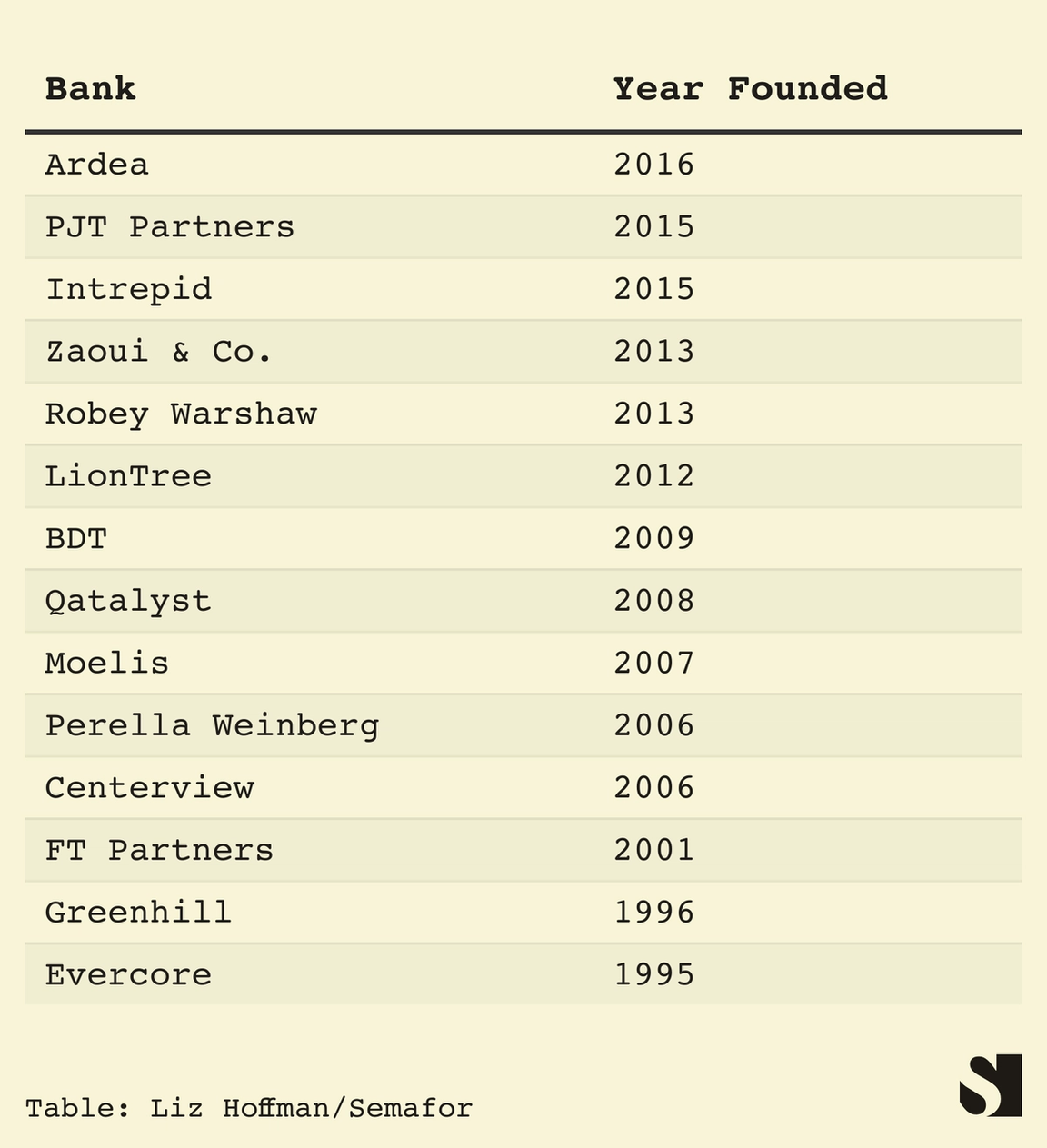

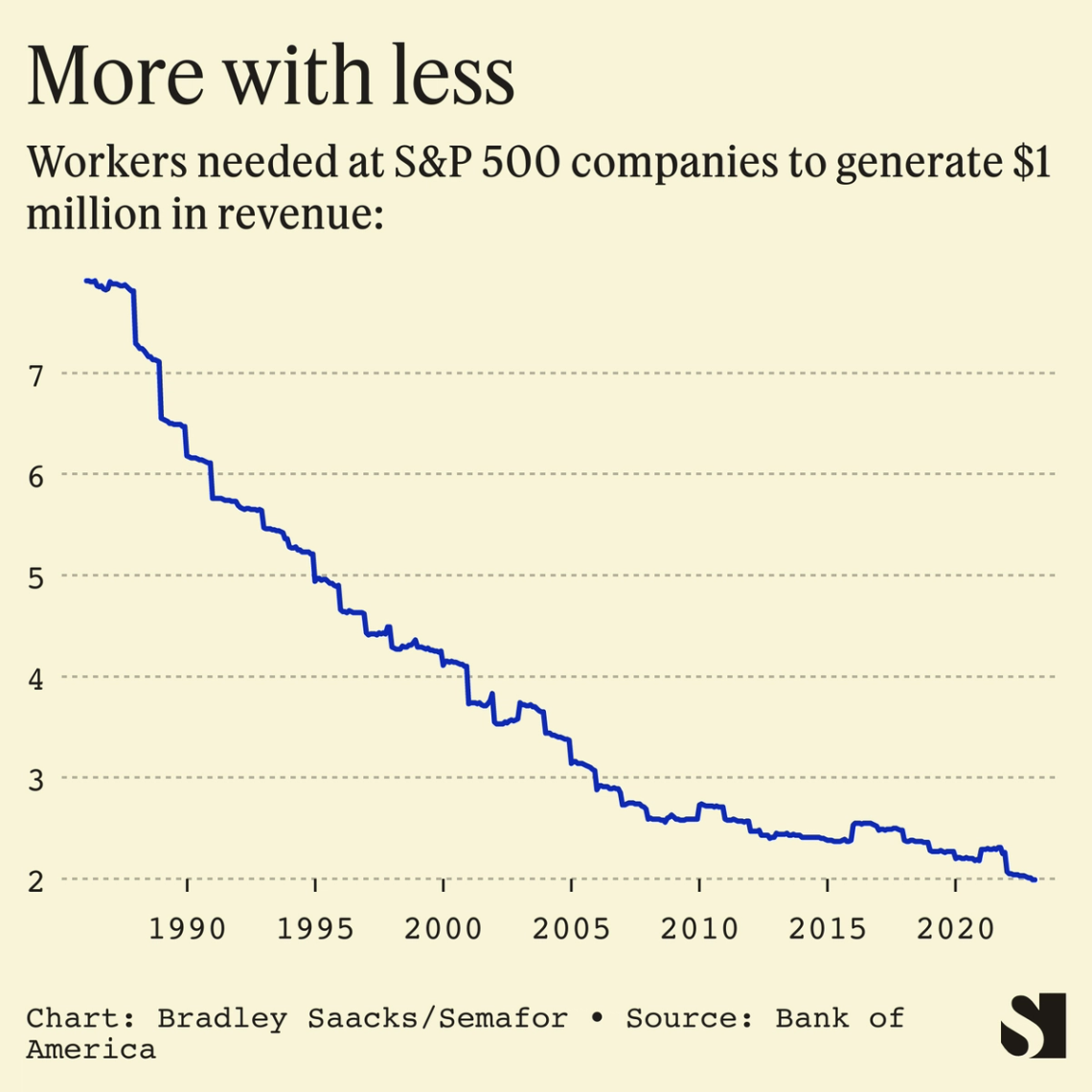

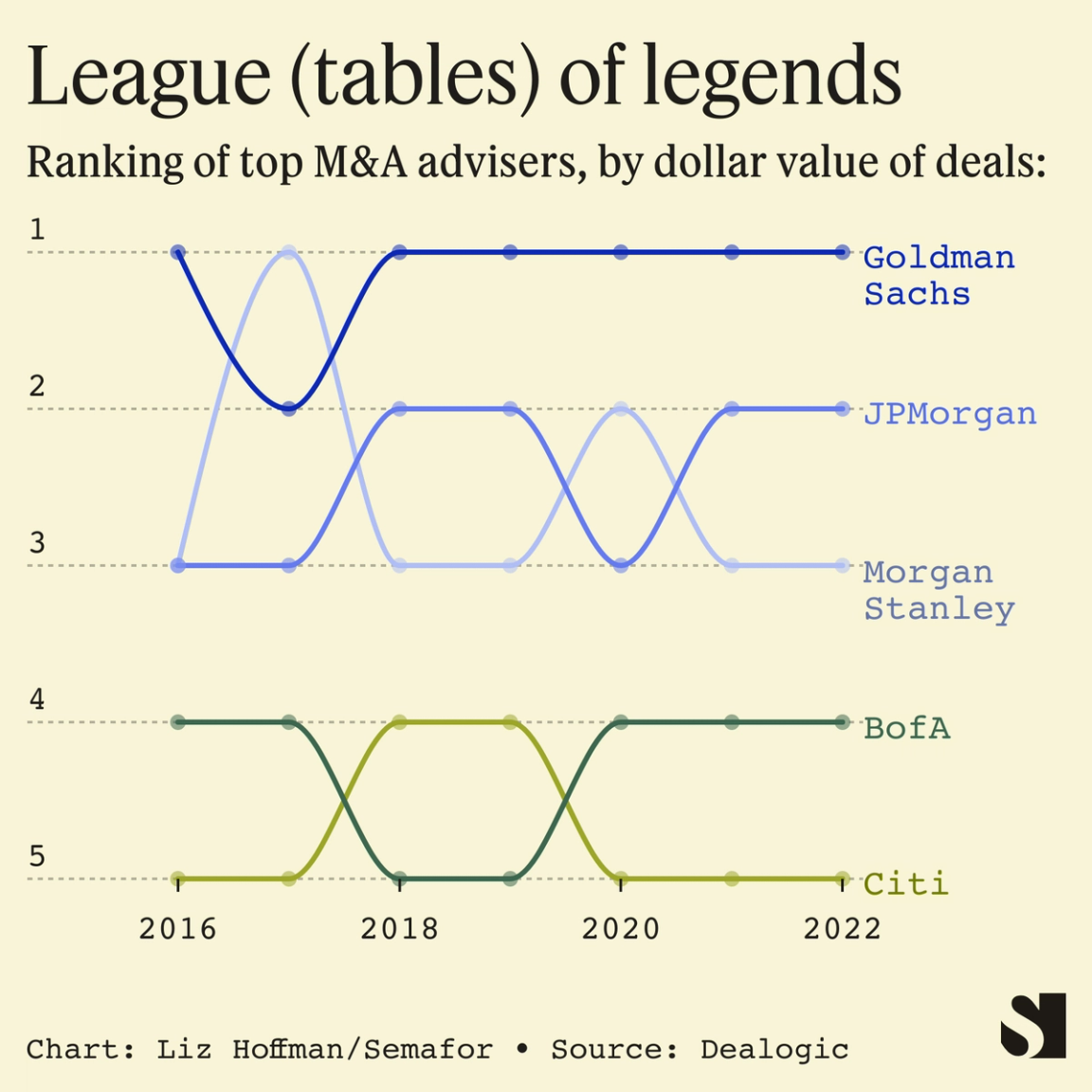

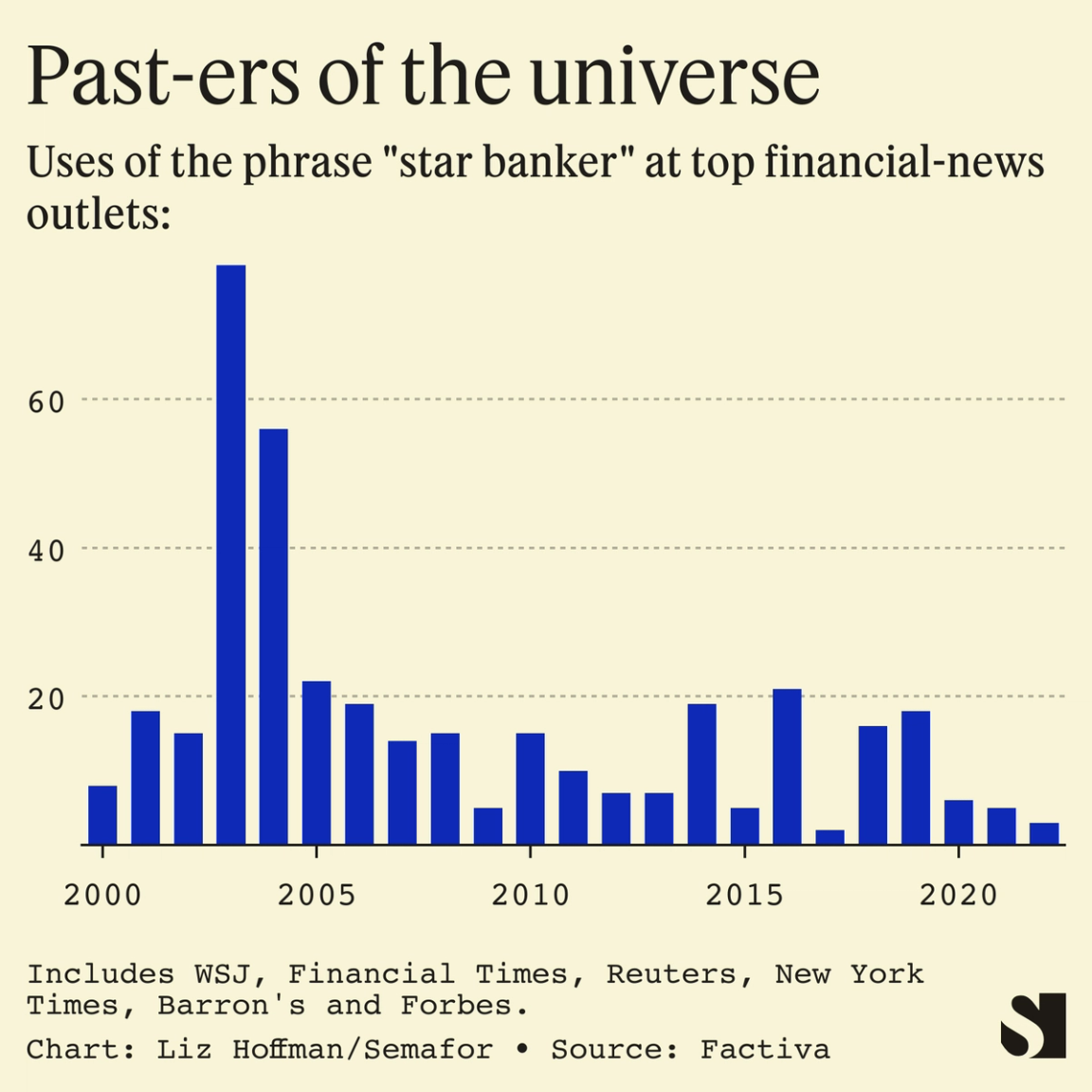

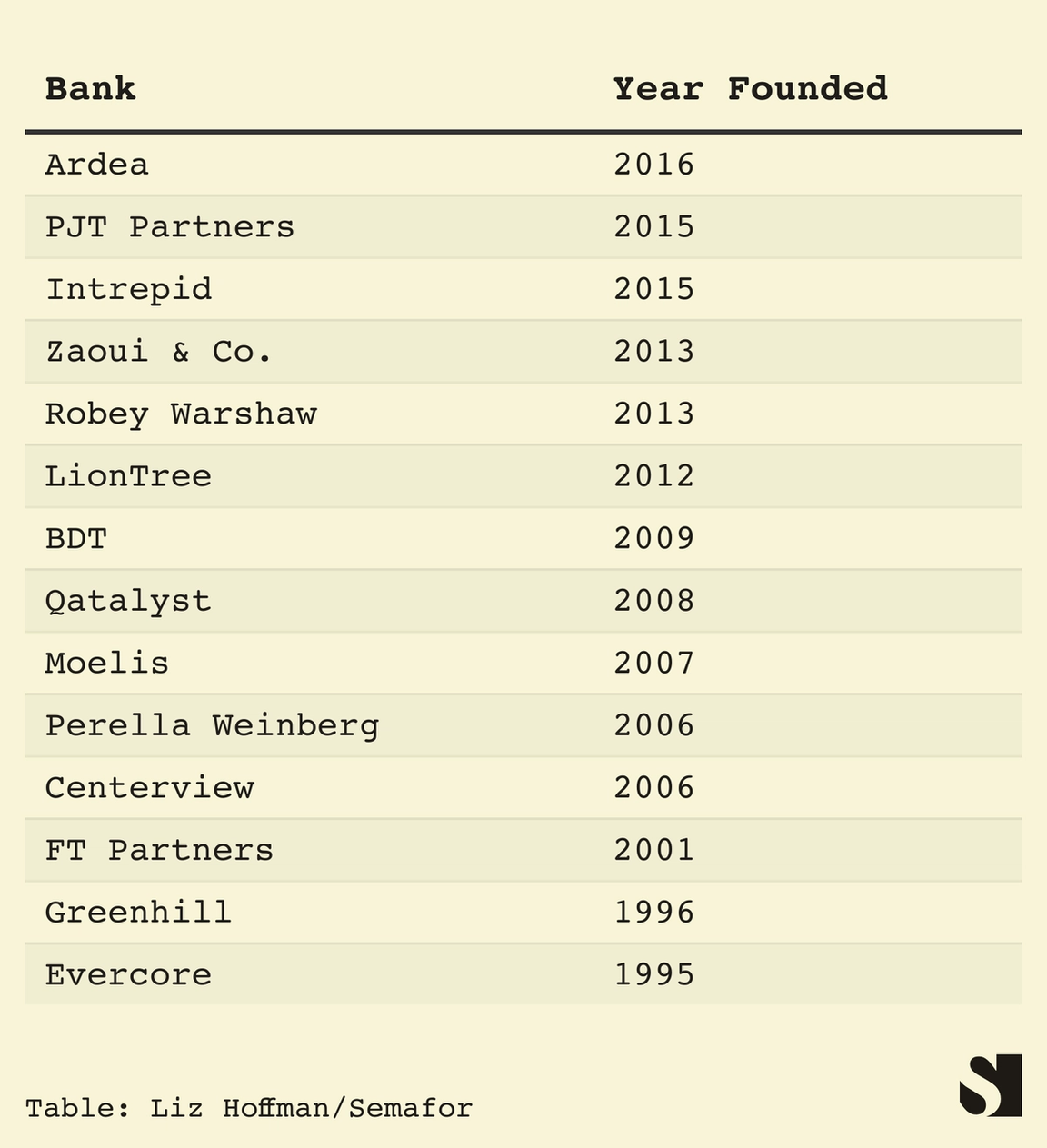

THE FACTS A decade ago, Morgan Stanley’s star dealmaker left the firm, hung out his shingle, and quickly landed plum roles on two giant deals for Verizon ($130 billion) and Comcast ($45 billion) that spun heads across Wall Street. Paul Taubman’s success seemed to herald a golden age for superstar bankers, with enviable Rolodexes and unshackled from their giant firms, which were then mired in a post-crisis funk. In the years that followed, boutiques founded by big-bank breakaways peeled away business from the old guard. That era is over. Taubman was the last major big-bank star whose firm has made a meaningful dent in the M&A leaderboard. PJT Partners and a small group of older rival boutiques — Evercore, Centerview, Perella Weinberg — are profitable and elite. But they aren’t a threat to the existing Wall Street order. And almost nobody has followed behind them. Of the 20 most-active boutique banks tracked by Dealogic, only one, the Goldman Sachs superband Ardea Partners, was founded after 2015. The usual trio of big banks — Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan — have maintained their iron grip on the top of the annual rankings of merger advisers, with noticeably less of the headline-grabbing star wattage of decades past.  Fortune magazine has highlighted only one banker on its cover in the past five years and it was Citigroup’s new CEO, Jane Fraser, a former McKinsey consultant who made her name not as a swaggering dealmaker but as an internal strategy guru and clean-up specialist. LIZ’S VIEW The game has changed and so have the players. Deals have become more commoditized. Big companies now have sophisticated in-house teams that scour the market for takeover targets and analyze their own holdings for things to sell. Some have even hired former Wall Street stars to do it: Comcast and Thermo Fisher, two serial dealmakers, have former bankers running their internal M&A teams. The Wild West days of tactical M&A are gone. In the 1980s and 1990s, bankers engineered genuinely innovative moves — the Pac-Man defense, the poison pill, the cram-down tender offer. Since then, courts have sorted out which are kosher and which aren’t. And the rise of huge index funds that dominate shareholder registries has changed the game from a war of tactics to one of persuasion. (Cue the proliferation of specialized M&A communications shops.) “You can’t sprinkle the same magic,” said Ronald Barusch, who retired in 2010 after three decades as an M&A lawyer at Skadden. As the value of tactical brilliance dwindled, along came a new, all-important client group that couldn’t care less about it. Private-equity firms are the biggest fee-payers for big banks, and by and large are interested in one thing: financing. They don’t want hotshot bankers telling them what they should buy and how to do it, then charging them $50 million for the advice. They are, however, willing to pay up for debt, and that’s encouraged banks that once lived on the sell-side of transactions, like Goldman Sachs, to start angling to represent buyers and provide the loans they need, which come with huge fees. Consider one of today’s last superstar bankers. Michael Grimes, Morgan Stanley’s whisperer in Silicon Valley, has enough name recognition with tech founders to have struck out on his own. He’s guided nearly every major tech IPO of the past decade and displayed the showmanship of generations past. (He moonlighted – for years! – as an Uber driver in a successful bid to win that coveted IPO for Morgan Stanley.) But boutique banks don’t underwrite stock offerings, and much of Grimes’ magic is tethered to Morgan Stanley’s balance sheet and stock-trading desk.  There’s a generational element at play, too. Bankers who might have retired in the years after 2008 instead stuck around to rebuild personal wealth decimated by the crash. Their underlings, who would now be in their forties and potential household names, instead stayed on the bench. On Wall Street that’s called the “execution team,” the army of bankers who prepare Powerpoint presentations, run the numbers, and deliver the all-important but rote “fairness opinion” evaluating a transaction’s merits. They are increasingly crucial to the assembly-line nature of modern dealmaking, but are unlikely to ever be called “M&A jedis.”  A last reason, I think, is harder to capture, but clearly reflective of the post-2008 Wall Street. There is simply less tolerance for ego. “There’s no way a bank today — or its regulator — is going to allow a thirty-something hotshot take on the [profile] that Jimmy Lee did,” said Richard Farley, a partner at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, referring to JPMorgan Chase’s legendary money man, who died in 2015 as one of Wall Street’s most-revered bankers. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT The end game may no longer be launching a boutique. Seeing the fortunes made in private equity, some of the biggest names in M&A are trying their hand at a hybrid adviser/investor role. Why help bake the cake when you can eat it too? Goldman’s star tech and media banker Gregg Lemkau left in 2020 to run Michael Dell’s investment firm, then merged it with the family office advisory and investment shop run by Byron Trott, another former big-bank rainmaker. Skip McGee, a top banker at Lehman Brothers and then Barclays, invests alongside the energy companies he advises. It’s a revival for old-school “merchant banking,” which fell out of favor at big banks after 2008, and may be the new shiny object for star bankers who have seen their own paychecks decline and their clients get rich. CORRECTION A previous version of the story misstated the bank where Thermo Fisher’s head of M&A used to work.” The story has been updated to remove the error.” |