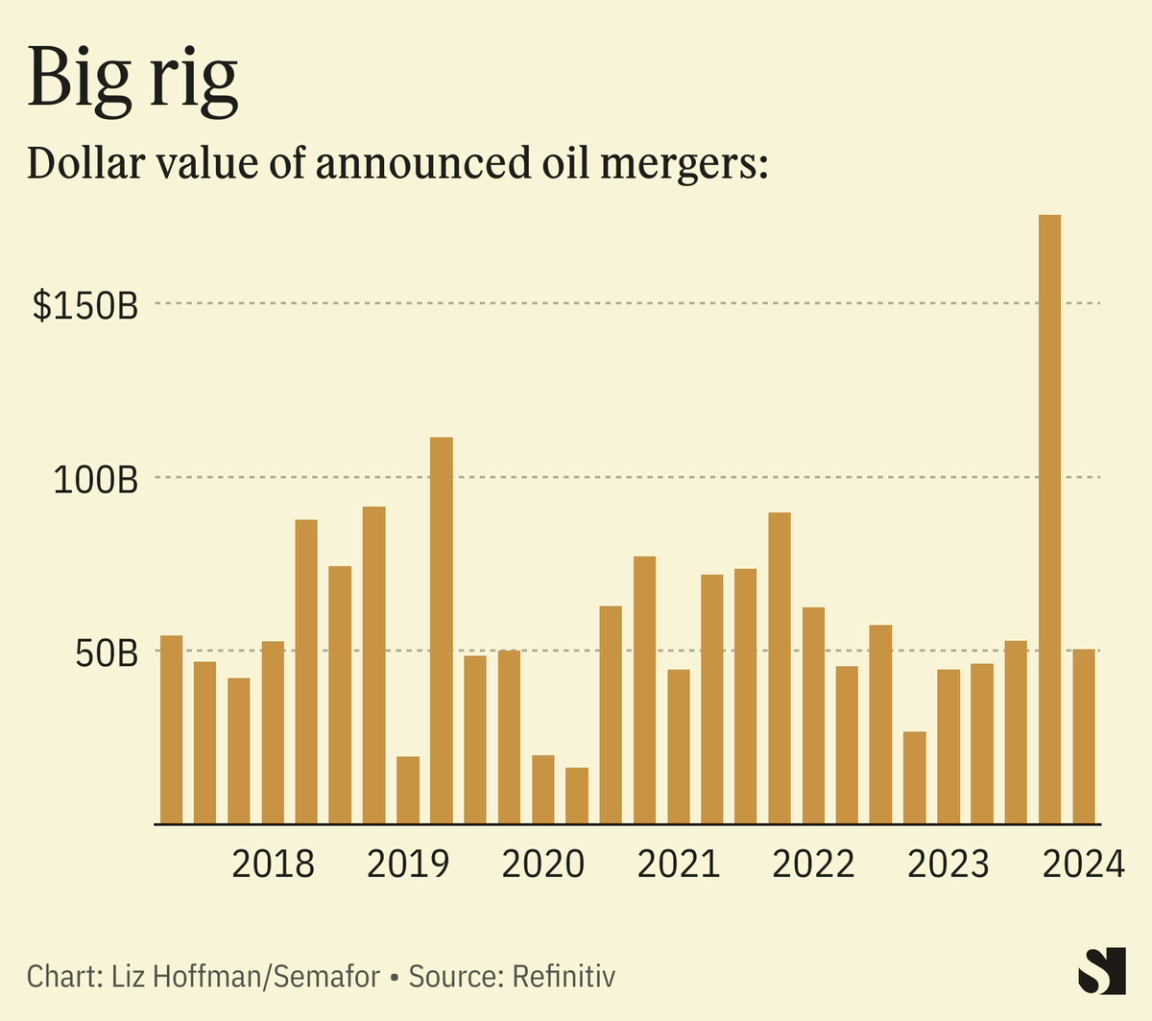

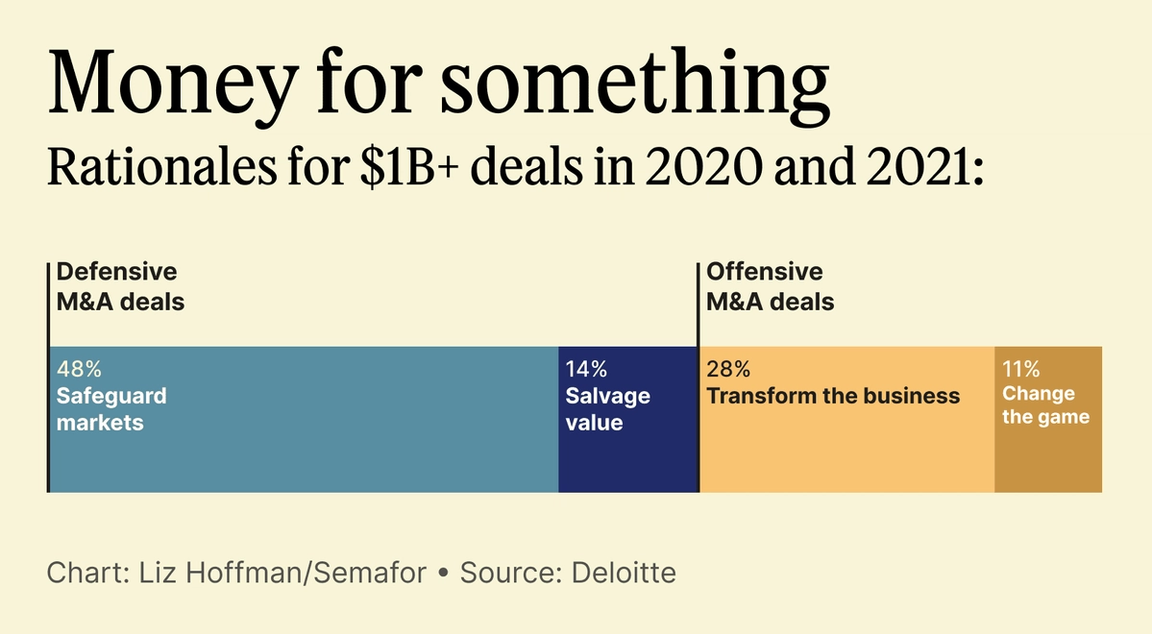

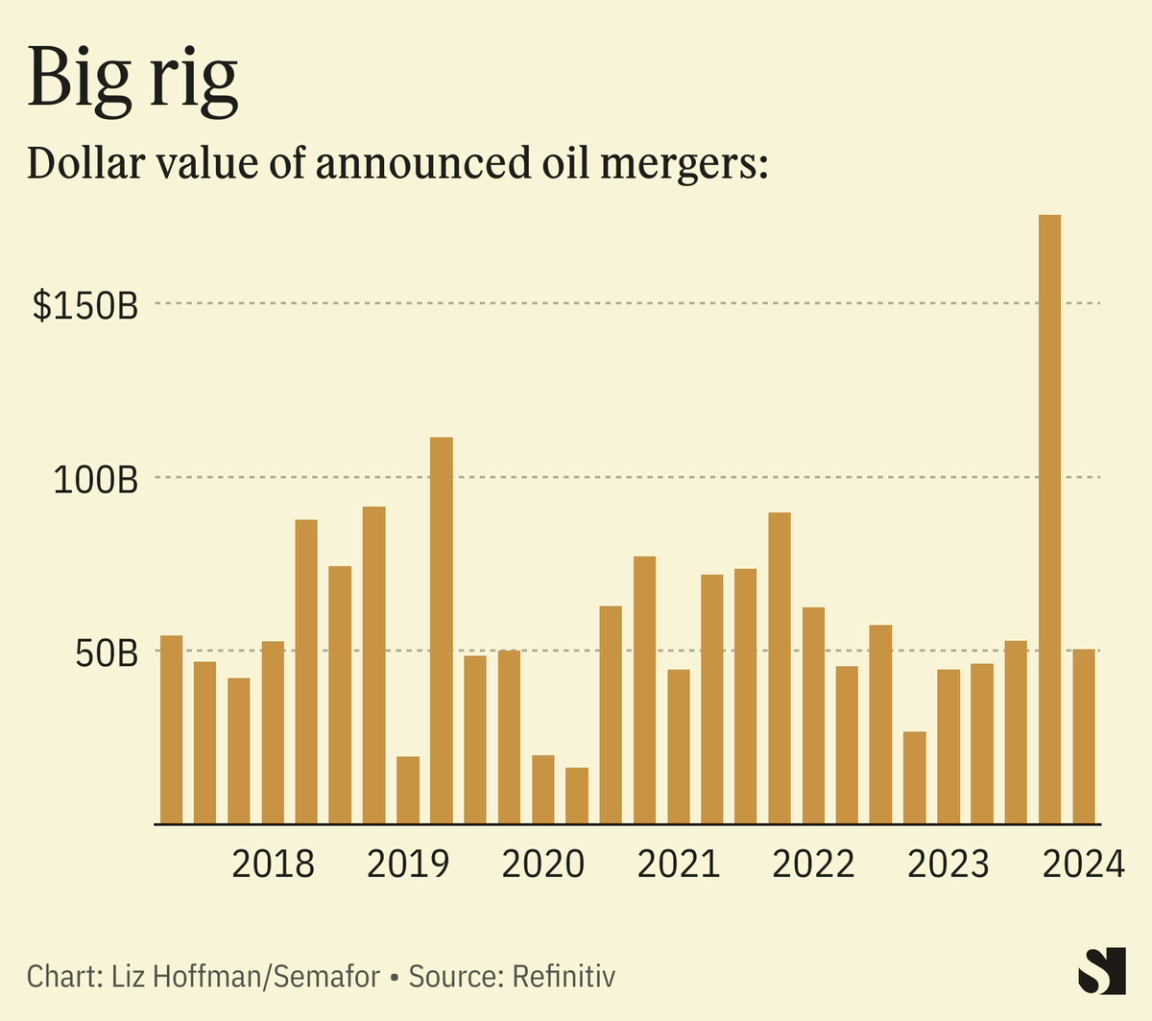

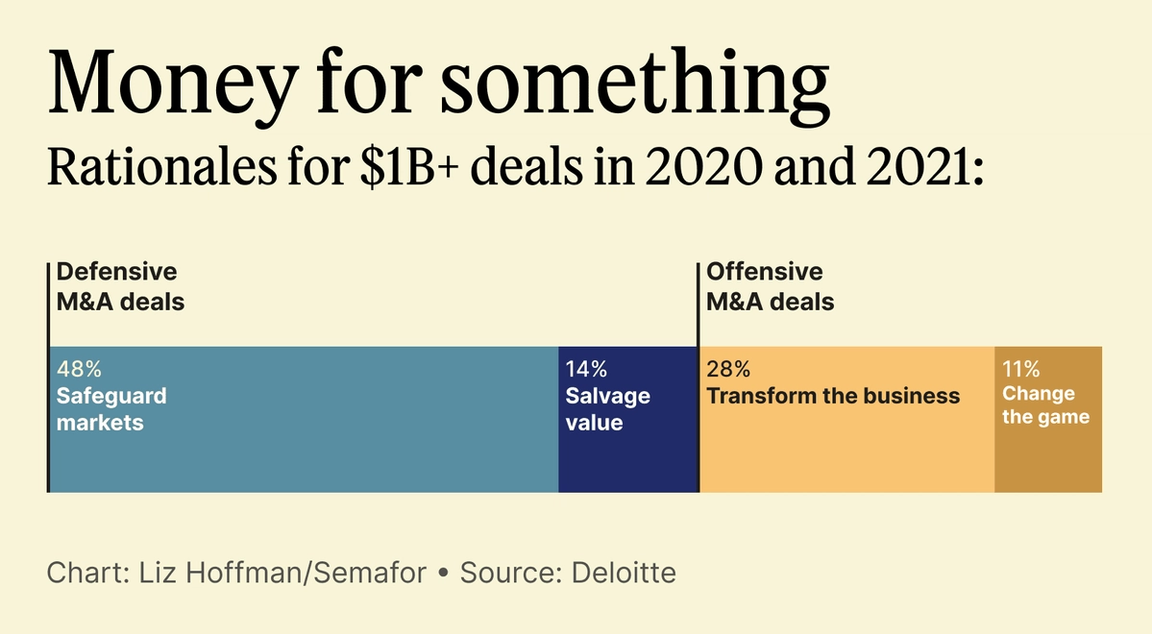

THE NEWS The run of deals in the oil patch show an industry trying to squeeze the last drops — literally — of oil demand that’s sure to decline, though when is anybody’s guess. Diamondback’s $26 billion takeover of Endeavor, announced yesterday, creates a behemoth in the Permian Basin, home to oil and gas blasted out of rock by newer technology. The U.S. is now the world’s biggest oil producer, thanks to heavy drilling in New Mexico and Texas, where the two companies have neighboring acreage. Despite efforts to transition to clean energy, global demand for oil is expected to rise for at least another decade. The key now is for companies that pump it to bulk up. Rather than the frenzied drilling of the 2010s — which fueled the American energy boom but delivered scant profits — companies are now focused on making existing wells more profitable, said Mark Viviano, who runs an $800 million portfolio of energy stocks at Kimmeridge Energy Engagement Partners. “It’s an arms race for operational scale and investor relevancy,” he said. In shale’s wildcat days, smaller and nimbler firms had a first-mover advantage on the best acreage, he said. “Now it’s all about efficiencies — lowering costs, returning cash, being able to reduce emissions off a bigger footprint, collecting data.” Similar dynamics are behind a spate of takeovers in the area, including Exxon buying Pioneer for $60 billion, Chevron buying Hess ($53 billion), Chesapeake buying Southwestern ($7.4 billion), and Occidental buying CrownRock ($12 billion), all announced in the past four months. “You’ll run out of quality targets before you run out of buyers,” said Bruce On, who runs the energy transaction group at EY in Houston. “Nobody wants to be left without a partner.”  The CEO of French giant TotalEnergies said this week that policymakers and climate protestors are naive to think oil demand will decline dramatically anytime soon and said his company, the world’s fifth-largest energy firm, will keep investing in oil. “I need to continue to be strong in oil and gas… people are first buying your shares because of that,” Patrick Pouyanné told the Financial Times. About two-thirds of Total’s capital spending goes to fossil fuels, and the rest to its lower-emissions power business. Viviano made a comparison to tobacco stocks. By the early 2010s, investors knew cigarettes were fading but were unsure how quickly. So tobacco companies hunkered down, bulked up, and returned cash to investors. By 2020, Altria had returned $53 billion to shareholders in dividends and buybacks, more than the entire company was worth at the start of the decade, and had outperformed the S&P 500. “That’s what we’ve argued the energy sector needs to do,” he said. “You don’t really care if oil goes away in 10 years if you’ve gotten all your money back by then.” Despite broad global consensus, low-carbon technologies face serious challenges — an estimated $18 trillion investment shortfall, red tape, and waning political and investor support for corporate environmentalism, particularly as geopolitical turmoil makes energy security a priority. “There’s this growing realization that the energy transition might not be as plug-and-play as economists thought, and that oil and gas are going to be necessary for a while,” EY’s On said. LIZ’S VIEW When industries are growing, everyone can benefit, and it suits companies to let a thousand flowers bloom. Snap can build spectacles that nobody buys, Netflix and Spotify can throw money at Harry and Meghan, and investors are generally happy to pay for all of it. This happened during the shale boom in the early 2010s. Companies plowed their profits back into new wells, helping to make the U.S. a major energy producer but sapping their profits. Investors didn’t get much out of it and quickly soured, the same thing that’s happening to streaming companies (and Snap) now. Thus the consolidation chatter in Hollywood. It’s a question of when, not if, oil demand will peak and clean energy will replace fossil fuels, and the industry is preparing.  There are two ways they might do that. One is to make major acquisitions in clean energy — the “transform the business to safeguard the future” bucket in Deloitte’s chart. But as my colleague Tim McDonnell told me when I asked, “oil companies like molecules, not electrons.” (You can sign up for Net Zero, Tim’s must-read newsletter on the energy transition, here.) Pouyanné dismissed the idea of buying a big renewables company, even at current bargain prices. “I don’t need Ørsted,” he told the FT, of the offshore wind developer whose shares are down 75% since 2021. “What do they bring to me?” The other is to squeeze the remaining profits out of the oil business and, in the meantime, place smaller, in-house bets on renewables. That’s the wave of producer tie-ups we’re seeing now. Diamondback’s CEO is promising to wring $550 million out of the merged company. Investors seem to believe him: Shares rose 9% yesterday, unusual for any acquirer but especially one that’s cutting its stock buybacks as part of the deal. (Side note: That bump hands another $1.8 billion to Endeavor’s founder, wildcatter Autry Stephens, who becomes America’s richest oilman. Some deals using stock as currency have provisions that add or subtract shares if the price swings sharply up or down; this one doesn’t.) |