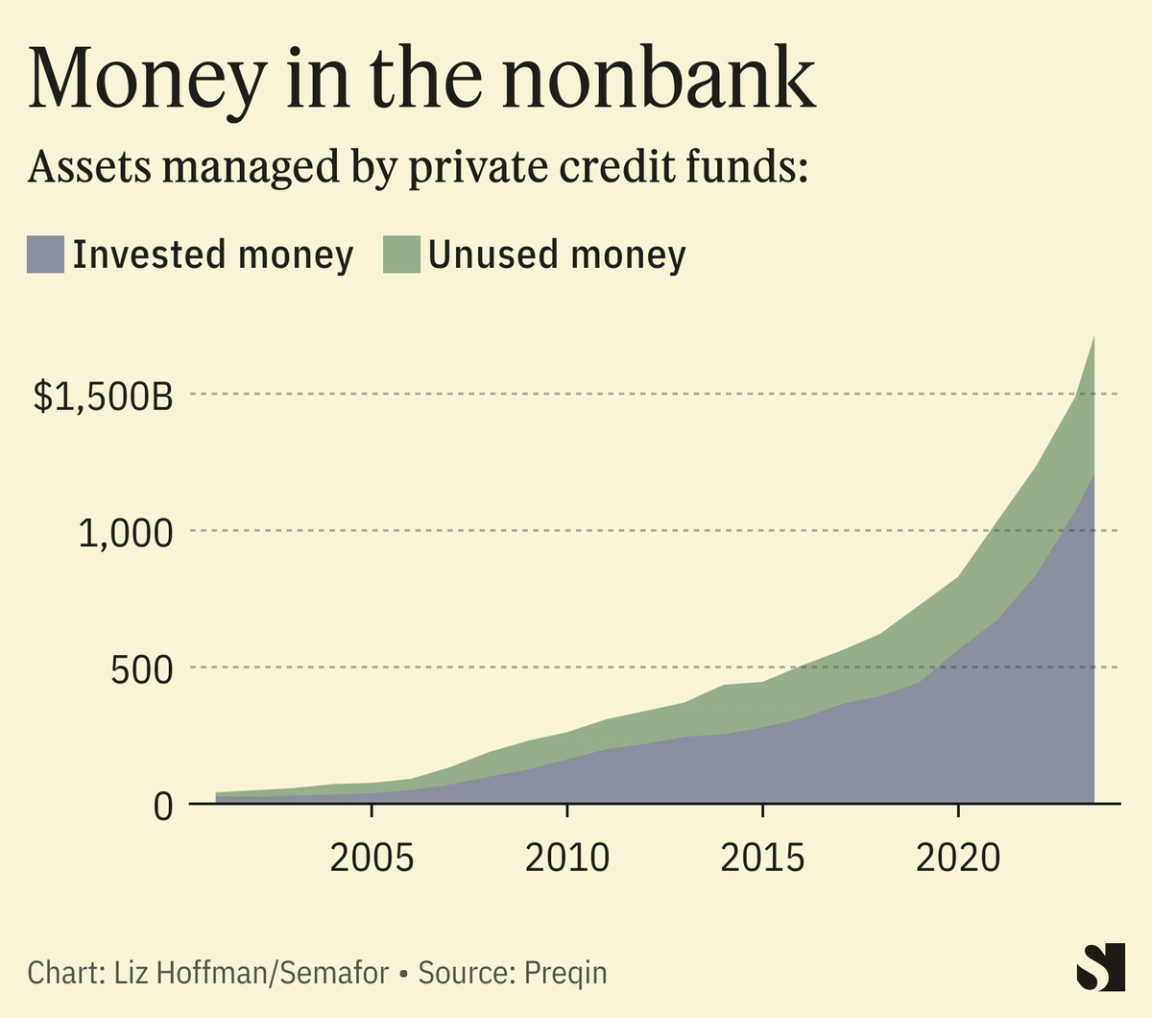

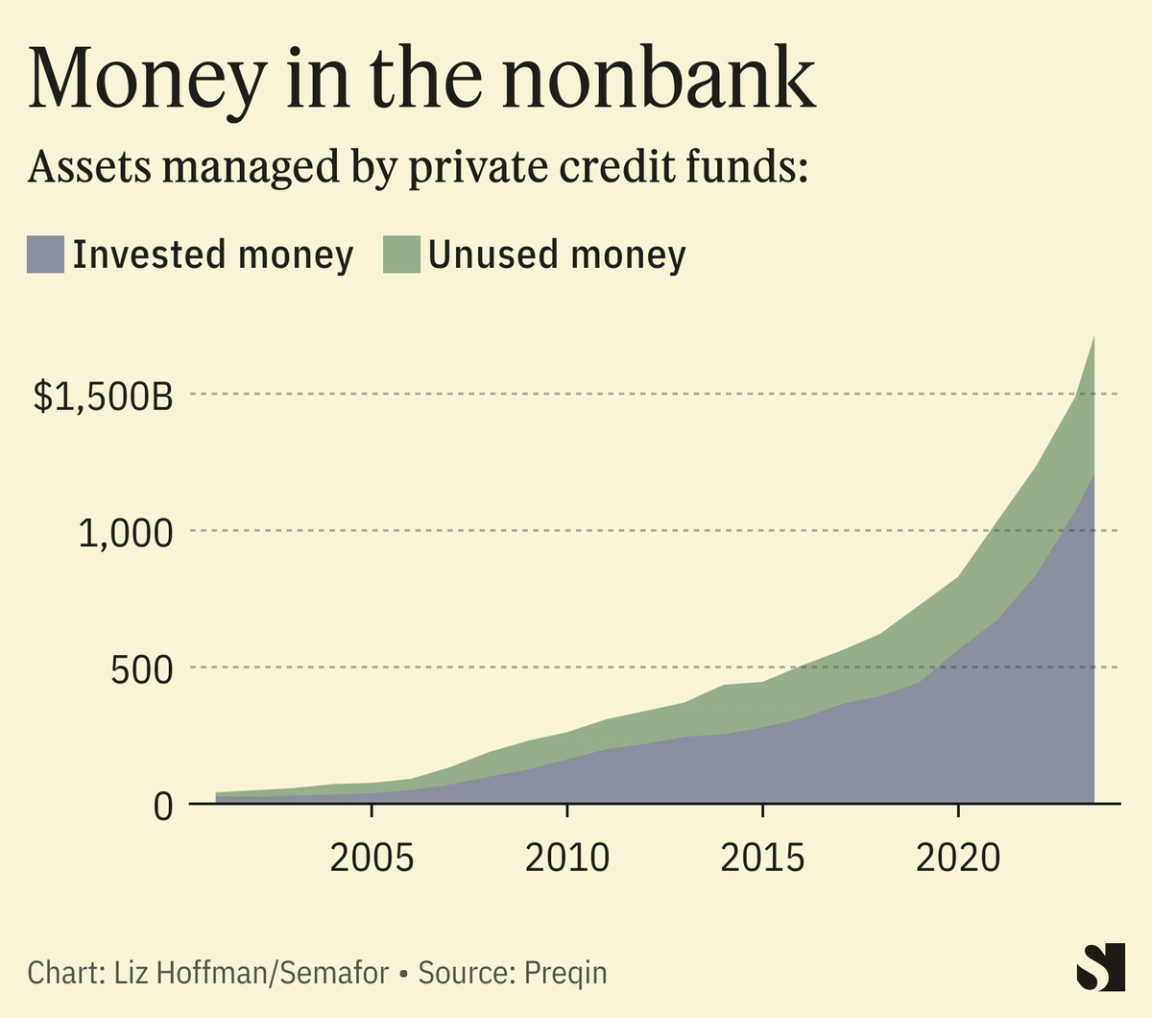

THE NEWS Wall Street banks have lost out on billions of dollars in fees to private lenders. A few have figured out how to get some of that money back. As private lenders muscle in on banks’ bread-and-butter business of corporate lending, JPMorgan, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, and others have built sizable businesses lending to these upstart competitors, which are eager to juice their own returns with that favorite of Wall Street tools: leverage. This lending casts these two camps more as frenemies than existential rivals in a game that is “less zero-sum than it seems,” said Dee Dee Sklar, who ran this business at Wells Fargo until retiring in 2019. Numbers are fuzzy, but industry participants estimate that banks have lent as much as $150 billion to private credit funds, backed by loans to companies that are mostly midsized and owned by private-equity shops. The loans charge 3% or so above a baseline interest rate, which suggests the half-dozen banks that are active in this space are making $4 billion a year. That’s not enough to compensate for the business they’ve lost to nonbanks, but it’s significant revenue, and gets more favorable treatment by regulators because it’s seen as safer. JPMorgan has about $30 billion of these loans outstanding and Goldman Sachs has about $10 billion, to credit funds run by Apollo, New Mountain, and Blue Owl, according to people familiar with the matter and corporate filings. Banks’ lending business is “being hollowed out by private credit,” said Jim Fellows, president of First Eagle Alternative Credit. “So what do they do? They come back and lend against it. They’re always chasing that fee.” Funds like First Eagle borrow against their loans for the same reason KKR borrows against its buyouts and homeowners borrow against their houses: It boosts profits.  LIZ’S VIEW There are no new hammers on Wall Street, only new nails. Investors borrow against stocks. People borrow against their houses. Private-equity firms borrow against the cash flows of the companies they own. The universe of asset classes — buckets of sufficiently valuable things that can be borrowed against, bet against, securitized, collateralized, indexed, and generally tinkered with for profit by enterprising minds — has expanded to include art collections, lottery winnings, and litigation awards. Private credit is a logical addition to that list. From essentially a dead start before 2008, it has grown into a $1.6 trillion market, and BlackRock estimates it could more than double over the next five years. “That’s an entire asset class that has to be financed,” one banker told me last week. Since 2008 it’s become hard for banks to lend to risky companies. But it’s easy for banks to lend to the credit funds that do lend to those companies. They’ve traded one client set that regulators don’t like for another set that, for the moment, regulators are fine with. In the Rube Goldberg machine that is financial regulation, it makes perfect sense. The question is where the risk is hiding. So far, these loans look fairly safe. Banks lend 40 cents or so on the dollar, leaving ample room for things to go badly before they take losses. Loans are secured by dozens of individual borrowers, which should make it less risky. But that’s what boosters of subprime mortgage bonds said in 2007. Housing prices wouldn’t fall everywhere at the same time, they argued, so a pool of mortgages from Phoenix and Orlando and Chicago was safer than any single loan. We know how that went. The companies that private credit funds lend to are facing soaring borrowing costs, and more and more are having trouble paying. Most of them are smaller companies that are less able to weather downturns, and most of them make their money the same way, by selling software and services to corporate customers. The loans usually aren’t rated by firms like Moody’s, whose track record is far from flawless but which are at least a check on Wall Street’s worst instincts. It’s not hard to see how assumptions about private credit could be faulty. “Correlations do sometimes go to one,” Fellows told me. Adding debt on top would only exacerbate a bust. Read here for the view from the Bank of England. → |

|