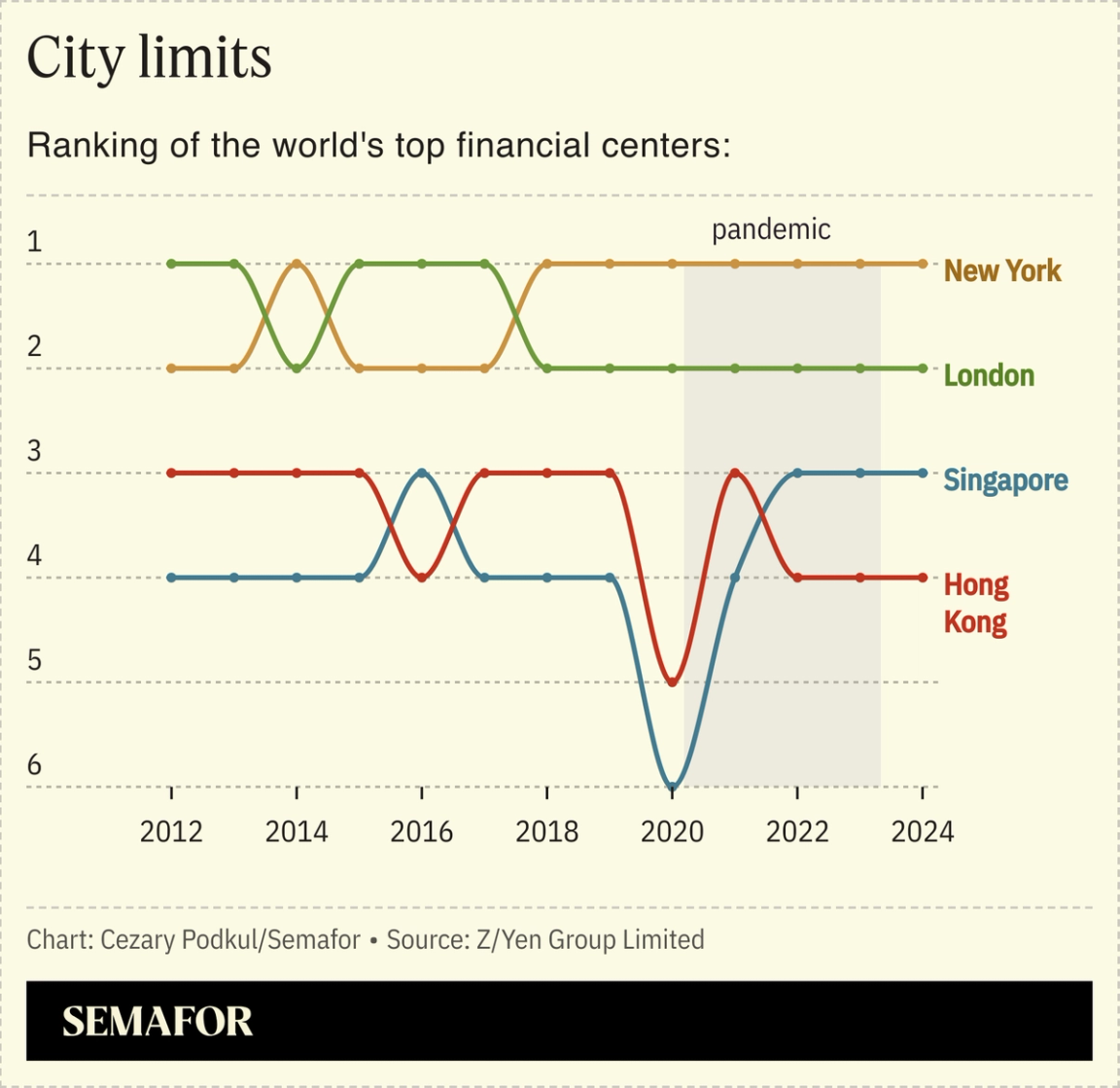

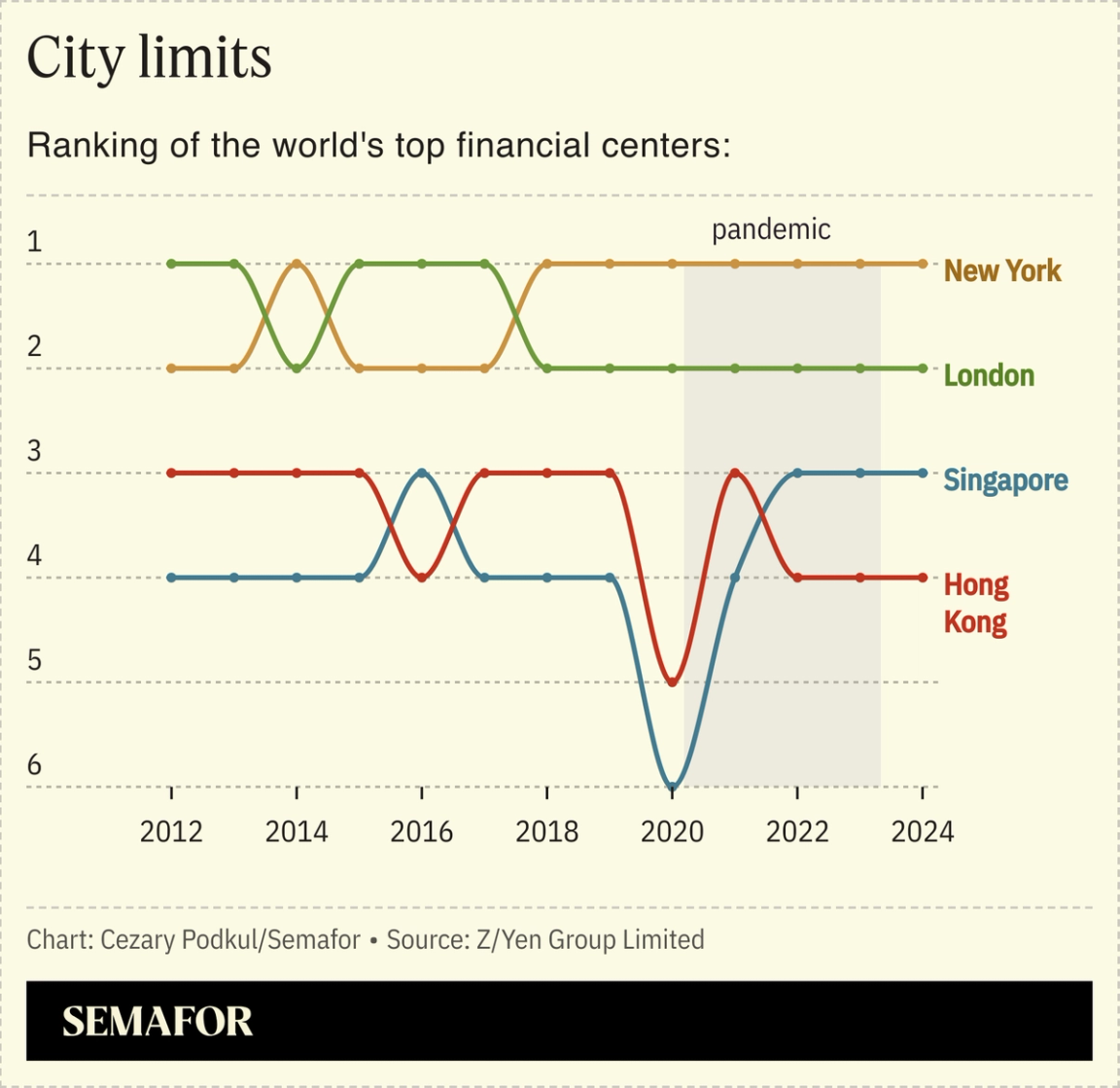

THE SCENE Milton Friedman called it his favorite economy, a “laboratory experiment” in freebooting capitalism. “If you want to see how the free market really works,” he said in 1980, with Victoria Harbor behind him, “this is the place to come.” Hong Kong is now at an economic crossroads, trying to keep the take-all-comers commercialism that made it a hub for global companies and markets, while also trying to prove its political fealty to Beijing. As China tightens its political grip, Western capital and talent have been voting with their feet. Draconian COVID-19 travel restrictions sent many expats to Singapore, where they’ve mostly stayed. In 2022, Singapore overtook Hong Kong in a closely-watched ranking of financial hubs. Companies including FedEx and Commerzbank have moved their regional headquarters out of Hong Kong. A new national security law implemented last month, which prescribes steep punishment for vaguely defined offenses, has further spooked foreigners.  The benchmark Hang Seng Index was the worst-performing major stock market in the world last year and in January dipped under 15,000 — roughly where it was when the British handed Hong Kong over to China in 1997. (Chief Executive John Lee, speaking here this week, preferred to say the Hang Seng had “consolidated.”) Hong Kong’s stock exchange, once a crown jewel of Asia, slipped behind India’s in total market value last year.  Photo by Simon Jankowski/NurPhoto via Getty Images Photo by Simon Jankowski/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesThe city’s finance and information technology sectors shed some 20,000 jobs during the pandemic, sparking fears of what one Hong Kong-born entrepreneur called an “irreversible brain drain.” They’re being replaced by workers from China: Nearly all the visas granted under a 2022 program meant to import skilled workers went to mainland Chinese. Chinese companies have moved in, too. After Uber Eats shut down its Hong Kong operations at the end of 2021, Beijing-based Meituan moved in. Chinese battery giant CATL, which isn’t state-owned but has seen its operations steered by Beijing over the years, is setting up research facilities in Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s solution for its ailing stock market: Get mainlanders to invest.  — Additional reporting by Cezary Podkul LIZ’S VIEW Hong Kong has been written off before, Roach notes, after communist riots in the 1960s, the 1997 handover to China, the Asian financial crisis, and the SARS outbreak. The city has mostly proven its critics wrong — its relatively open borders and light touch on regulation and enforcement have been a magnet for entrepreneurs willing to look past its other shortcomings. Proximity to China, too, has been a major draw. But the crackdown on dissent hits at the heart of those incentives; the key questions will be whether the influx of Chinese capital and talent can substitute for the global money and businesspeople that are leaving, and whether Hong Kong’s leaders will learn to wield their new powers with a lighter touch — or at least signal more clearly to the business community what is, and isn’t, out of bounds. Fortune magazine famously ran a cover story with the headline “The Death of Hong Kong” in 1995. It’s a story that’s still ahead of its time. Hong Kong’s economy is expected to grow 2.9% next year and it still has more rich people than any other city in Asia, according to one recent study. “While some have voiced their disappointment over what could well be short-term market volatility, others have expressed strong confidence in Hong Kong, and the abundant opportunities ahead of us,” Lee, the city’s chief executive, said in a soundbite that played on taxi radios throughout the week. He urged the 3,100 conference attendees to “work hard, play hard, and do remember: spend hard.” Another question is whether being more tethered to China’s economy will import its problems, too. China is facing slower growth, lingering trauma from draconian Covid lockdowns, long-term population decline, and a real-estate bubble that is threatening a 2008-style bust. Foreign investment is at 30-year lows. Few economists believe China’s official economic data — an audience question here yesterday about the reliability of those numbers drew a laugh from the audience — but even they show an economy with serious problems. “Hong Kong is caught in a vice,” said Morgan Stanley’s former head of Asia, Stephen Roach, whose column in the Financial Times declared the city all but dead. “It’s going to have an exceedingly difficult time growing with China on the skids.”

|