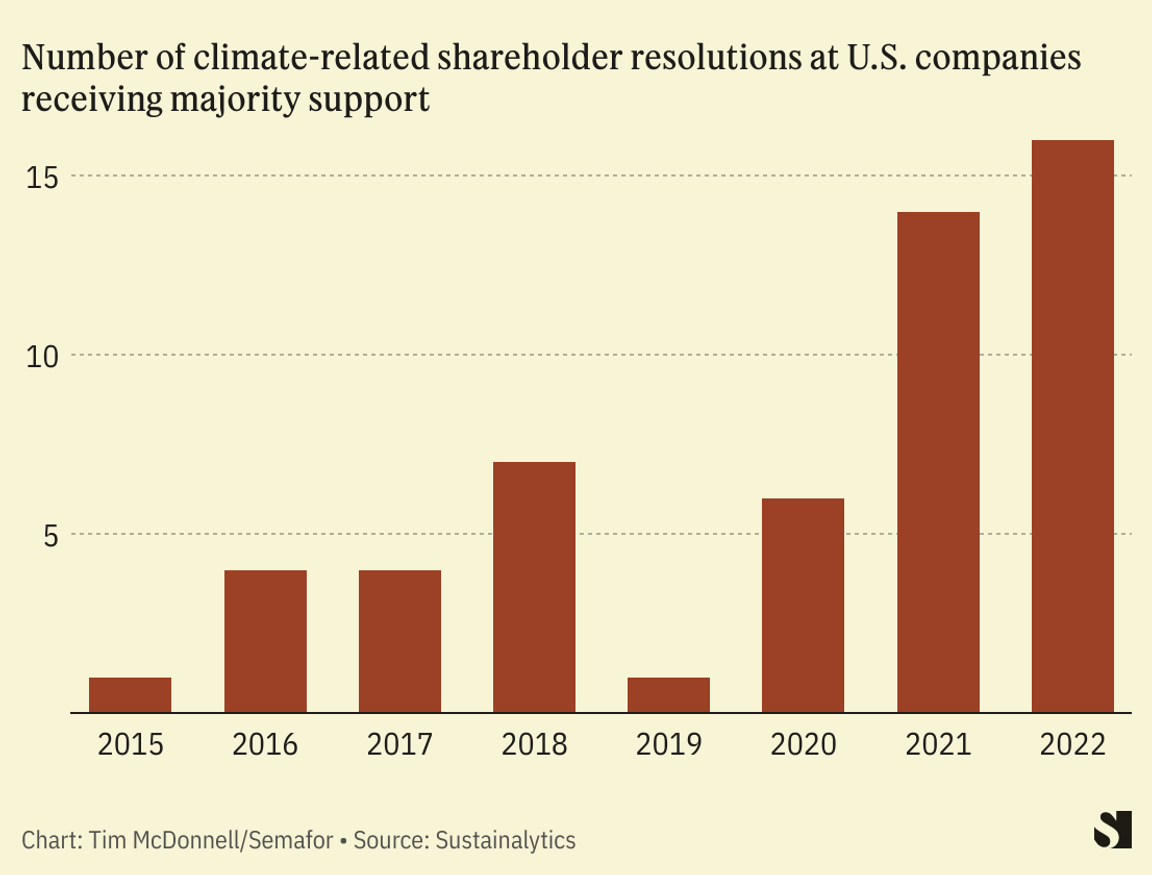

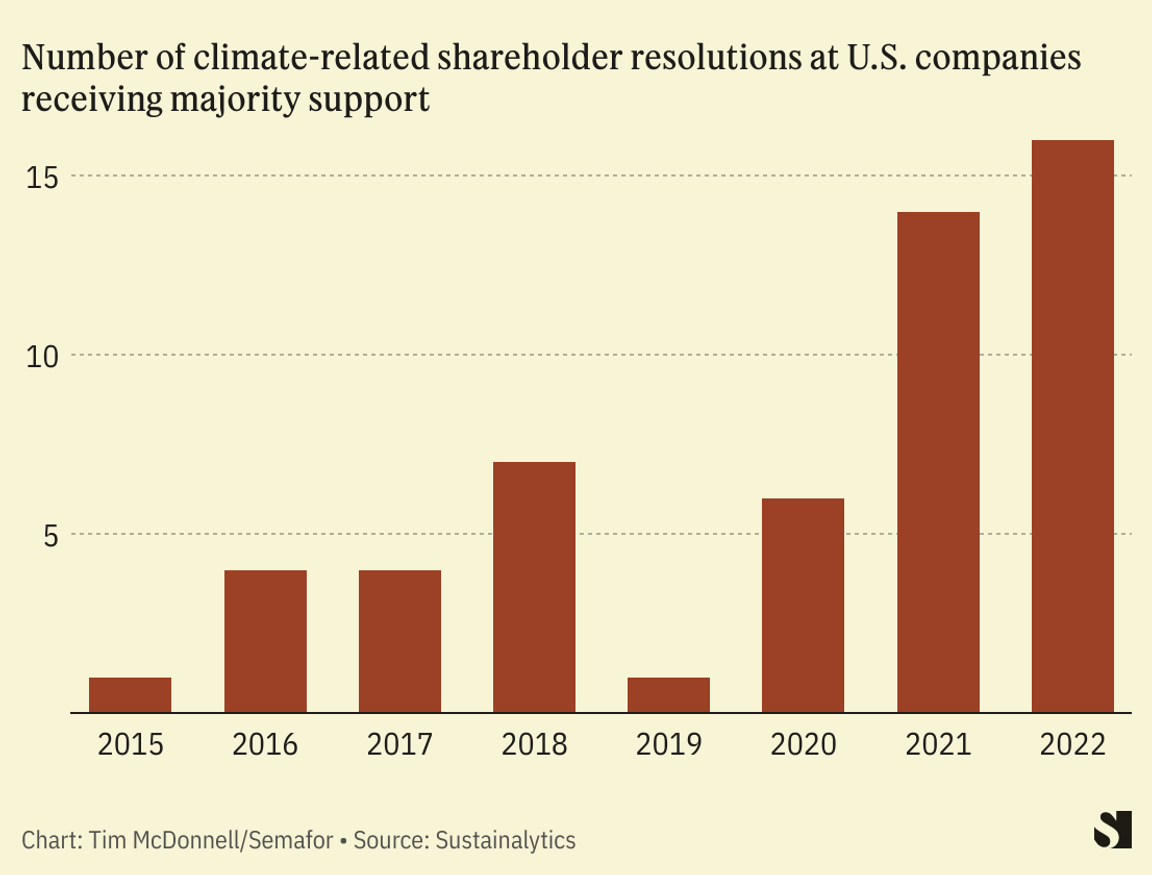

REUTERS/Carlos Osorio REUTERS/Carlos OsorioTHE NEWS Companies ranging from banks and insurers to retailers and fossil fuel producers are facing a record-breaking wave of demands from their shareholders to strengthen their climate policies, which will come up for votes during annual meetings that will mostly occur in the coming weeks. Shareholder activist groups are advancing resolutions that call on businesses to withdraw from anti-ESG lobbying groups, remove fossil fuels from pension fund holdings and loan books, set hard company-wide emissions reduction targets, and disclose more detailed information about their climate plans. These resolutions are drawing support from some large institutional investors, including the $270 billion New York State pension fund and asset managers like Legal & General. TIM’S VIEW The likeliest outcome of this year’s proxy voting season is that most climate-related resolutions will fail (last year, they garnered about 40% support on average). But that doesn’t make them failures, per se. Because the “Big Three” asset managers — BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street — control a significant chunk of most large U.S. companies, resolutions are unlikely to pass without their support. And those firms are becoming increasingly circumspect in their approach to climate resolutions, partly because of pressure from Republicans pushing state-level policies to penalize financial institutions that they view, rightly or wrongly, as ESG activists. Climate resolutions also face opposition from proxy advisory services like Glass Lewis, as well as the targeted companies themselves. But whether these resolutions pass or not is an imperfect measure of their success. Companies are highly motivated to avoid an embarrassing proxy defeat, and so signs of shareholder discontent raise the stakes for corporate boards to find a compromise or risk losing control. Support for climate-related corporate action is quickly rising. Five years ago, only about 5% of ESG resolutions passed, compared to more than 20% in 2021. And last year advocates notched several major wins including requiring ExxonMobil and Chevron to report on their financial exposure to climate policy and cut their methane emissions, and for Costco to eliminate its supply-chain emissions. According to shareholder advocacy group Majority Action, institutional investors managing nearly $10 trillion have committed to vote against board directors who oppose aligning their company’s capital spending with the Paris Agreement.  “Majority votes indicate that a company has misread the shareholder electorate,” said Eli Kasargod-Staub, Majority Action’s executive director. “So most of them want to anticipate, negotiate, and preempt the consequences of majority votes.” U.S. banks, for example, which are a frequent target of climate resolutions, are gradually rolling out more stringent climate targets (albeit still short of what’s required for Paris). Even oil and gas companies are proactively disclosing more emissions data, a longtime demand of shareholder activists. KNOW MORE One subject on which shareholder activists and companies remain at loggerheads is on proposals to reduce or eliminate “Scope 3” emissions — those from businesses’ supply chains and customers. For banks, Scope 3 targets effectively require purging fossil fuel companies from loan books, and for fossil fuel companies themselves, they mean a fundamental change of the business model. These proposals are particularly attractive, though, to pension fund managers, for whom higher Scope 3 emissions at any one company translates to greater climate damage in the future, putting the rest of their portfolio at risk. “If you’re a universal owner [of shares in companies across the economy] and you look at your portfolio, there are a small number of bad actors that harm the whole portfolio,” said Andrew Behar, CEO of the shareholder group As You Sow. That message doesn’t seem to have caught on at BlackRock. In a 2020 letter to clients, CEO Larry Fink wrote that the firm “does not see itself as a passive observer in the low-carbon transition.” But the company’s latest corporate engagement guidance in March — amid energy price spikes caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine and the mounting anti-ESG backlash — clarifies that “it is not our role to engineer a specific decarbonization outcome in the real economy.” This year will be a litmus test for the “Big Three” asset managers, Kasargod-Staub said, as to whether they “are going to place their short-term political self-interest as a firm over the interests of their clients through systemic risks to their portfolios.” ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT One crucial reason most climate resolutions don’t get majority support is that they focus on big-picture environmental or portfolio risks without clearly articulating how the proposal will help that individual company make more money, Chris James, founder and chief investment officer of the activist hedge fund Engine No. 1, said in an interview. Engine No. 1 occupies an interesting middle ground in the proxy wars. It led a successful campaign to replace some members of Exxon’s board in 2021, and James is adamant about the need for economy-wide decarbonization. But he bucks the ideology of most shareholder activists by arguing that banks and fossil fuel companies need flexibility in how they approach that goal. Blanket restrictions, he said, could backfire by hobbling the ability of oil and gas companies to participate in scaling up low-carbon technology — which would also be a missed opportunity for shareholders to profit. QUOTABLE “[Most shareholder activists] are missing the mark around what is really going to be a realistic and impactful way to decarbonize. We have to find environmental metrics we can link back to value creation. Otherwise you end up in an ideological battle which is not very productive. If a company embarks on a strategy that is solely about decarbonization and not value creation, shareholders will revolt, and the CEO won’t last.” — Chris James THE VIEW FROM SASKATOON The proxy season didn’t get off to a very auspicious start for activists. Royal Bank of Canada — which ranked as the world’s top financier of fossil fuels in 2022 — held its April general meeting in Saskatoon amid crowds of climate and Indigenous rights activists, some of whom were restricted from entering the meeting despite holding shareholder proxies. Three separate climate-related resolutions failed to receive majority support. A spokesperson for the bank said it is “confident in our ongoing engagement with our clients and our climate strategy.” NOTABLE - In its voting recommendations for shareholders, JPMorgan Chase argued against a proposal asking the bank to phase out lending to companies working to expand oil and gas drilling, saying that such a policy “would not be prudent at a time when analysts project that the availability of alternatives to fossil fuels will not be sufficient to meet increases in energy demand over the medium term.”

|