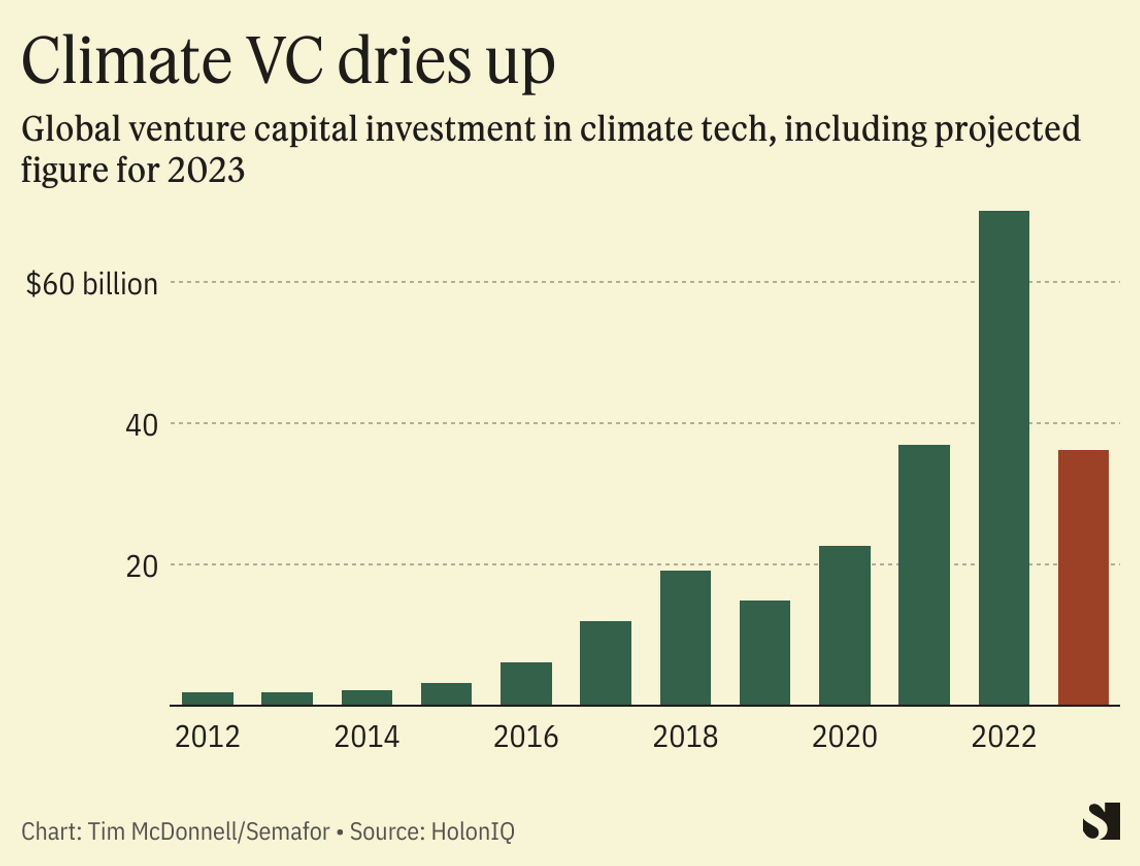

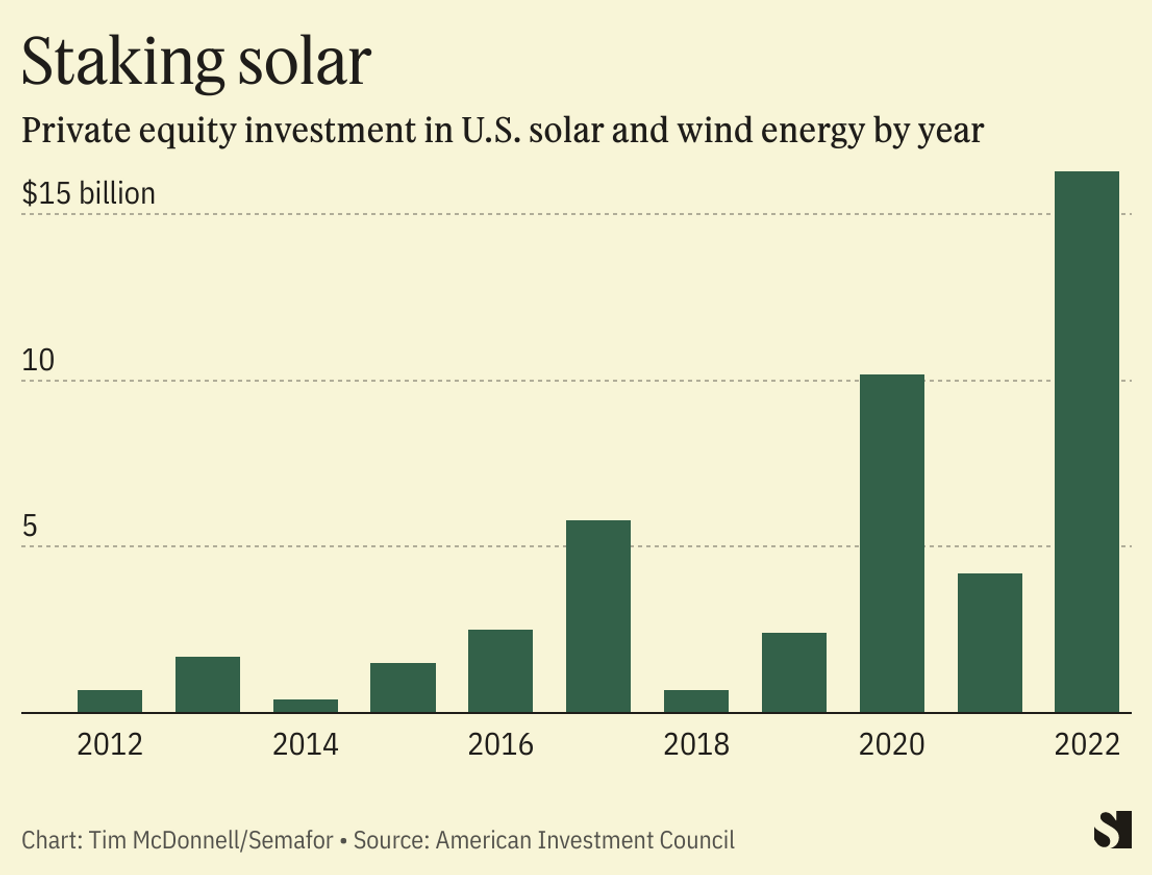

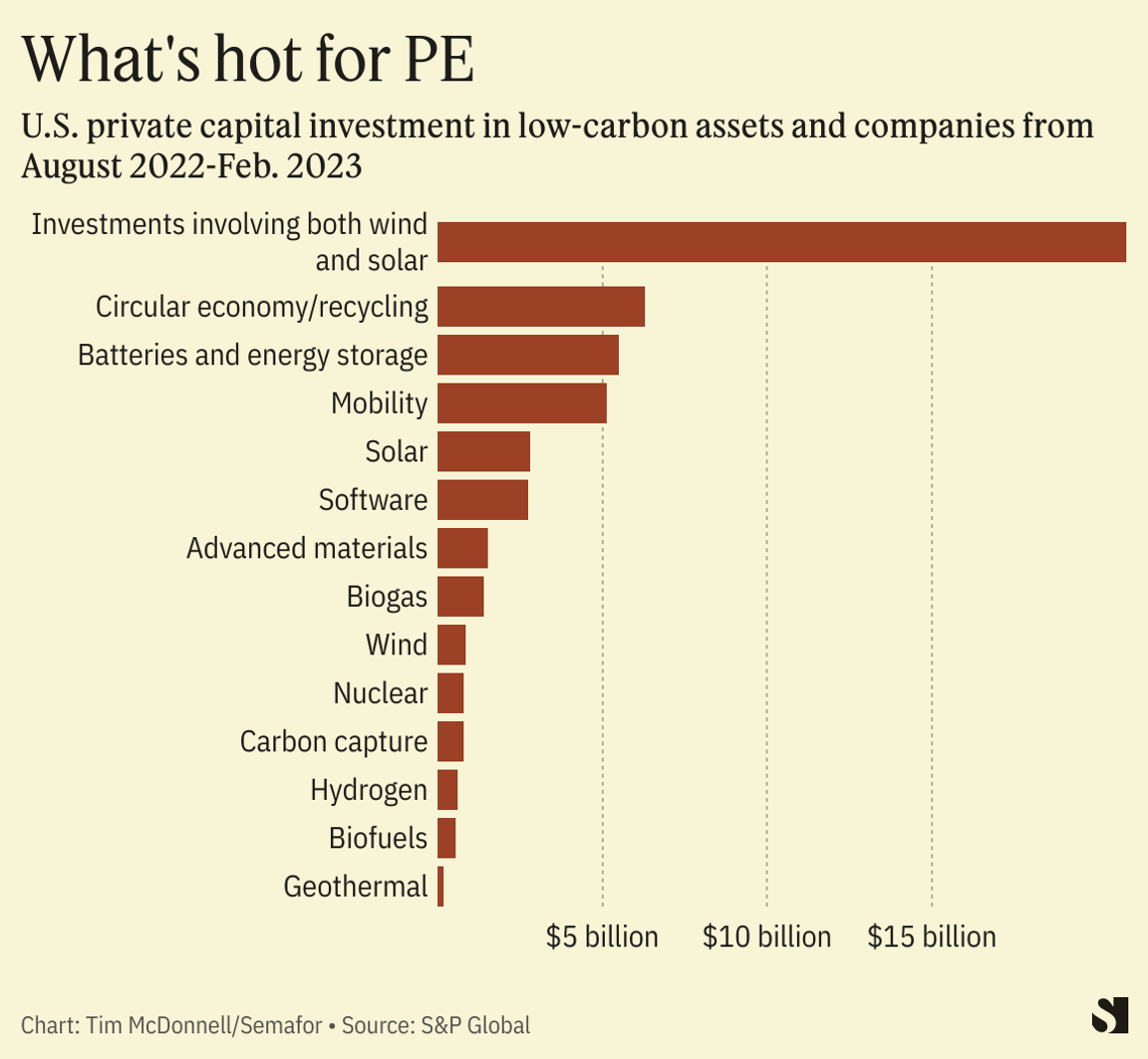

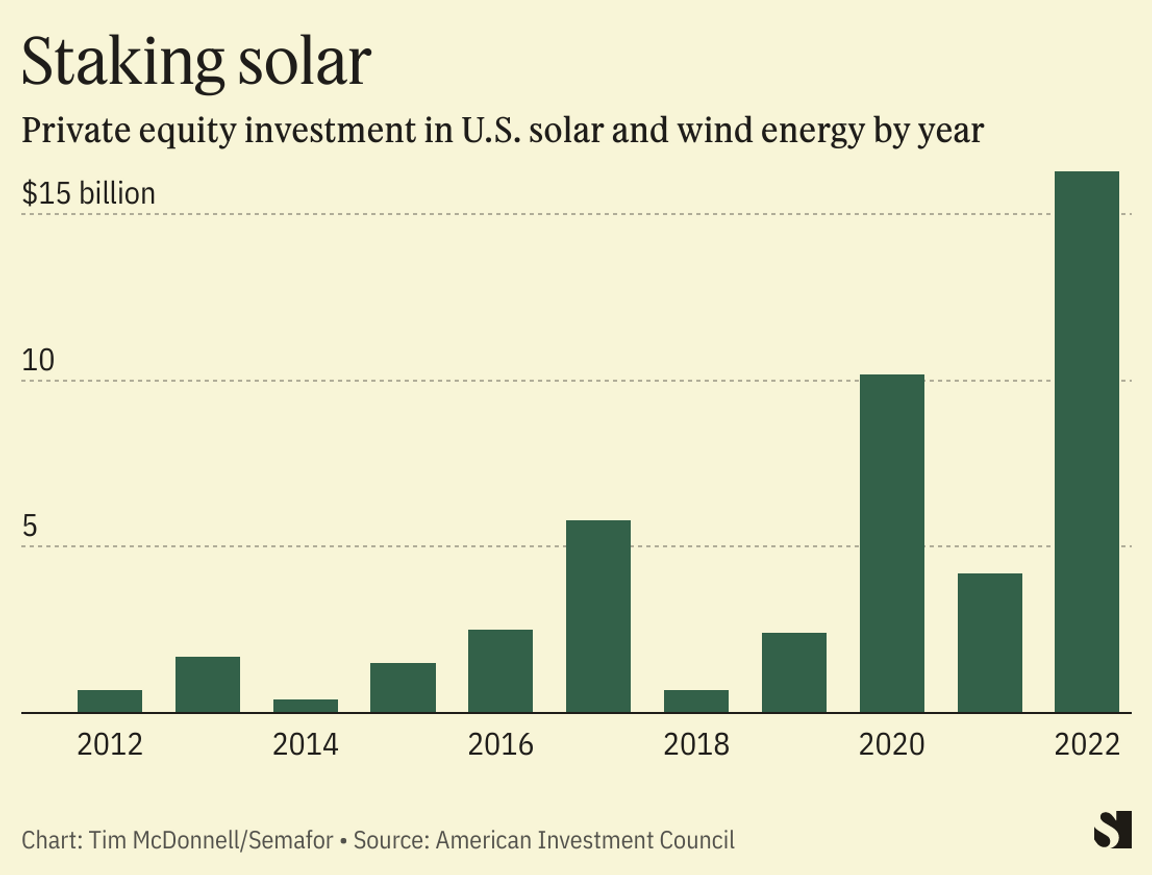

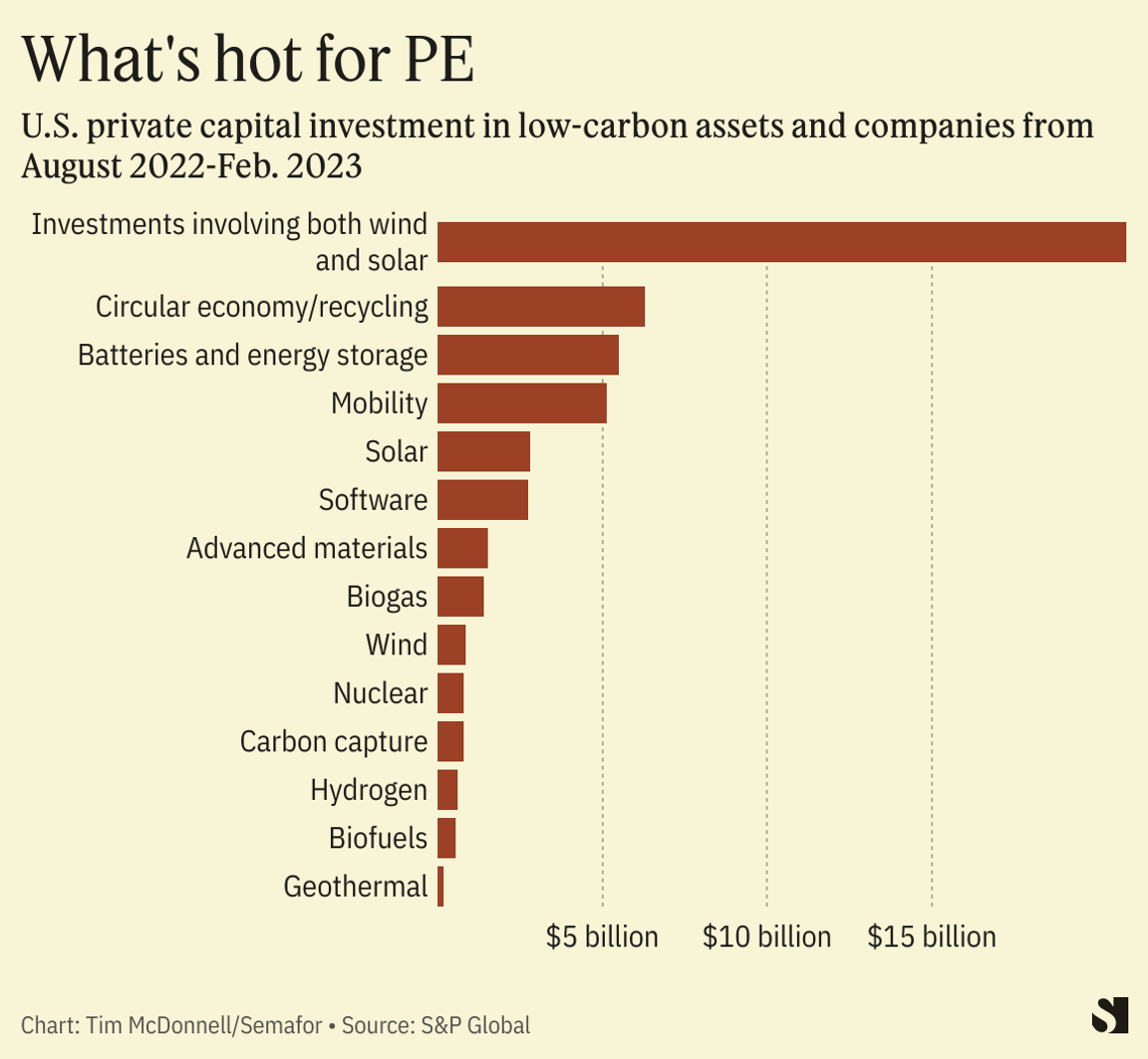

ADB/Flickr ADB/FlickrTHE NEWS Investment in the energy market is increasingly private. 2022 was a record-breaking year for private-equity investment in renewables and other clean energy companies, reaching more than $20 billion in the U.S. Firms like Carlyle and Brookfield unleashed more of the war chests they’d built up from pension funds, wealthy individuals, and other investors. Private equity is financing a growing share of the energy transition, and clean energy companies are waiting longer before going public, if they ever do. As a result, the energy economy is gradually transforming from one dominated by publicly traded fossil fuel companies into one dominated by privately held low-carbon ones that may operate with less oversight of their finances and operations by regulators and the public. “There’s been an absolute flood of capital into energy transition funds in private markets,” said Peter Gardett, executive director of research at S&P Global Commodity Insights, who authored a report on the subject last week. “It’s been remarkable how much of the work on the energy transition is being done in private markets.” TIM’S VIEW Private equity firms are well-suited to investing in low-carbon technologies. They’re able to front the large volumes of cash needed to build a wind farm or battery factory, and can be more comfortable waiting years to see a return than a public company that has to satisfy shareholders every quarter. A rash of climate tech companies that went public via special-purpose acquisition companies in 2021 and 2022 have since underperformed or gone bankrupt. “These investments require a significant amount of time and expertise to get up and running,” said Pooja Goyal, chief investment officer of Carlyle Global Infrastructure, who leads the firm’s energy transition portfolio. “You can’t have your thesis dependent on a quick flip to go public.” That’s a departure from the path Big Tech and other recent major economic transformations have followed, Gardett said, where companies get started with private venture capital and then aim to go public once they reach a certain size. Private equity investors in clean energy are holding on to companies longer, he said, “moving them from one private fund to the next and growing them along the way.” KNOW MORE Private equity will likely be indispensable to the goal of reaching $44 trillion in total global investment in the energy transition by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement climate goals. The economy is far off-track for that goal, with only $1.3 trillion invested in 2022.  Gardett said PE investment is ramping up because more multi-million dollar opportunities, attractive to large firms, are becoming available as demand for low-carbon energy grows. Tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act also make these projects much more enticing. And there’s further investment to come, Gardett said, with U.S. firms sitting on at least $180 billion in unspent energy transition funds. Large new PE funds targeting the energy transition are popping up all the time. In February, Brookfield said it will launch a second such fund this year to follow an initial $15 billion fund it closed last year. In the last week, Apollo Global Management launched a $4 billion energy transition fund and Hong Kong-based Kerogen Capital said it would raise $1 billion to invest in niche clean energy technologies like geothermal and small nuclear reactors. But even if fundraising slows in response to rising interest rates and other macroeconomic headwinds—venture capital for earlier-stage companies dropped in the first quarter of this year—these funds will be able to build more with less capital as the cost of clean energy technologies falls. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT  A risk of all this private investment, Gardett said, is that policymakers have less information about what exactly is being built than they do when capital spending plans are disclosed in public companies’ filings. “You can’t just build a lot of clean power and hope for the best,” he said. “If regulators can’t forecast accurately, power markets could be dislocated by surprise.” At the same time, private equity investment in the energy sector is still heavily skewed toward fossil fuels. A report yesterday from Global Energy Monitor and other research groups found that Carlyle’s portfolio invests $16 in fossil fuels for every dollar invested in low-carbon energy. That lopsidedness is intentional, Goyal said, because the firm is keen to snatch up high-carbon assets — pipelines, refineries, and the like — being sold off by traditional fossil fuel companies, or to buy a controlling stake in those companies as a whole, and push them toward decarbonization. THE VIEW FROM SCOTLAND On Monday, U.S. private equity fund Quantum Energy Partners announced a $373 million investment in an aging port facility in Inverness with a view toward redeveloping it as a hub for offshore wind services. The investment is a good example of how PE firms can lay the infrastructure groundwork for the renewable energy aspirations of oil and gas giants like BP and Shell, which have been snapping up North Sea wind leases. NOTABLE - The rush of private investors into clean energy has driven up the price tag for low-carbon assets, Gardett’s report notes. That may drive away some smaller investors. But ultimately, increased investment in energy infrastructure will lower the retail price of low-carbon power.

|